Barry Callebaut is the world’s biggest chocolate maker, responsible for one in every five mouthfuls. As a business-to-business company, it keeps a low public profile. Unknown to most consumers, BC supplies almost every famous chocolate brand behind the scenes.

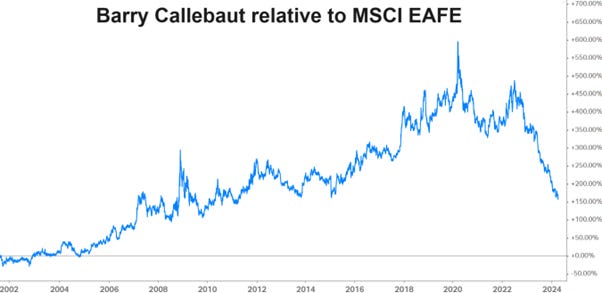

To international midcap investors, the name is far more famous. For twenty years it outperformed steadily (see chart), gaining a reputation as a rare defensive quality growth compounder, with an ever-rising rating of as high as 30x P/E to match. That it only compounded earnings at a mid single digit rate, with high reinvestment needs and a modest pay-out, seemed to be no cause for concern.

In the last two years the stock has melted. In this post, I walk through the salmonella scandal, the market slowdown, the hand grenade of a new CEO with his brutal restructuring plan, and most recently the shocking cocoa price spike, with its unpredictable impacts on the company.

My key findings are:

· BC’s balance sheet is weaker than it appears, and will come under further strain from the cocoa price spike.

· Consensus EPS estimates are too high. My base case scenario sits 10% below the mid-point, and my profit warning scenario is 30% below.

· Yet these negatives are well factored into the 45% share price fall from peak.

· Fundamentally, BC’s global #1 scale, strong market positions and unmatched experience give it the right to win market share and sustain superior returns on capital, compared to its smaller and disadvantaged competitors.

· The CEO’s drastic cost cuts are fortuitously timed to support earnings from FY25 and on, given the main cocoa price spike came after he launched his plan.

· The stock is attractively valued at 13.8x FY26 P/E on my base case, with an upper single digit growth outlook from there.

Barry Callebaut will publish its H1 results in two days’ time, on Wednesday 10th April, updating the market for the first time since cocoa’s most recent doubling. Nothing is certain except a volatile share price reaction in either direction.

For what it’s worth, my own trading position is as follows. Prepared for the worst, I have used recent weakness to accumulate a half position in Barry Callebaut ahead of the results. Depending on the content and the stock price move, I plan to add to my position after Wednesday.

Regardless, my aim is to share detailed research that is helpful to all who are interested in the name, whether they take a positive or negative view. Feedback is most welcome, as always.

Contents

· Introduction to BC

· Business model – three different activities in one company

· Brief history, including exit from consumer business and development of outsourcing model

· Salmonella incident and market downturn

· Ownership and context for switch to new CEO

· BC Next Level, the drastic restructuring programme

· Cocoa price spike and causes

· Possible impact on BC and peers

· Chocolate demand considerations

· Financial profile, including detailed balance sheet analysis

· My estimates and valuation

· Annex: market share and brief peer profiles

Introduction to BC

Barry Callebaut (BC) is the world’s biggest chocolate maker. It is vertically integrated, from sourcing and processing of cocoa beans in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, to production of liquid chocolate for huge food manufacturers on an outsourcing basis, to the sale of diverse gourmet, specialty and decoration products to small customers worldwide. It has 66 factories worldwide and 13,000 employees.

Chocolate is everywhere. As well as pure chocolate confectionery, BC provides the coatings on Magnum ice creams, chips and chunks for cookies and cakes, fillings in chocolate-flavoured breakfast cereals, powdered chocolate beverages for vending machines, and moulded chocolate decorations on fancy restaurant desserts.

BC’s customers range from the likes of Mondelez, Hershey and Mars to boutique patisseries and restaurants, plus every business in between that uses chocolate. In all cases, BC is a B2B-only company, and does not compete with its customers in selling to end consumers.

BC’s steady profitable growth is summarised in the chart below. The fiscal year runs to August.

Business model – three in one

BC’s three activities are very different in nature. To excel at all three within one group makes for a big cultural and management challenge.

Cocoa Products (24% of external sales, but the majority is for internal use) means upstream cocoa bean sourcing and processing. This is the realm of commodity traders like the ABCD agro-giants: Cargill and Olam are BC’s biggest competitors in this activity. Here, BC depends on its long experience of operating in the volatile source countries, especially in West Africa which provides 70% of global cocoa. BC must navigate wild price swings and manage counterparty risks and the interplay of financial and physical trades. At all times, BC must stay fully compliant with anti-corruption, anti-child-labour and anti-deforestation regulations, and in fact take a global industry lead in strengthening practices in these areas, while also dealing with and competing against peers that may be less scrupulous.

Steven Retzlaff has been BC’s President of Global Cocoa since 2008, and his senior team in West Africa is highly experienced. It is to BC’s credit that over its 30 years of existence it has a clean track record in terms of its regulatory compliance in cocoa sourcing. BC also has a clean commercial track record to date, with no major or exceptional losses linked to cocoa price swings. (The nearest such accident was modest losses related to Turkish hazelnut sourcing in 2004-05, as low-price contracts were not honoured by the supplier and had to be repurchased in the market at much higher prices. Notably, the losses fell within the then-newly-acquired Stollwerck German consumer business, which had less robust procurement practices than BC. It was since divested.)

Food Manufacturers (60% of sales) is BC’s operation of large liquid chocolate plants for multi-year outsourcing contracts. This business is about scale, lowest cost, highest productivity and absolute commitment to best operating practices for on-time, in-full delivery with perfect hygiene of all kinds. Different characteristics are needed to excel in this business, compared to the wild west of cocoa bean sourcing. BC’s track record was strong until the disastrous Wieze salmonella shutdown of June 2022, described below.

(I am reminded of beverage can maker Rexam, and its CEO from 2010 to 2016, Graham Chipchase. He was both highly successful and fantastically boring, with a dogged focus on his ‘three Cs’ of cash generation, cost control and improved return on capital. He went on to manage Brambles, another dull business where he has enjoyed further success. The point is that some businesses are intrinsically less exciting than others, and require a different temperament and culture to eke out a good return on capital.)

As for Gourmet & Specialties (17% of sales but a much higher share of profit), this requires innovation, creativity and great marketing and customer service. High-cost elements such as a global network of dozens of Chocolate Academy customer training centres are needed to maintain a strong Net Promoter Score and support high gross margins over the long term.

BC has generally done a good job in reconciling the different yet interdependent businesses. It has cycled through different management structures as it tries to square the circle of independence and integration.

Most recently, the separate Gourmet regional management teams are being removed. The BC Next Level restructuring programme sees a switch to a ‘country cluster’ structure, where a single country manager is responsible for driving both industrial and gourmet business locally. This is in the name of simplification, accountability and cost reduction.

History

The origin story of BC dates to the 1996 merger of the Belgian Callebaut with the French Cacao Barry, under the ownership of the Jacobs family of Switzerland. BC in its current form is therefore a surprisingly modern entity. The constituent businesses have know-how in sourcing and making chocolate that dates back to 1911 on both sides.

When Klaus Jacobs sold the family-owned business Jacobs Suchard to Philip Morris in 1990, he retained ownership of Callebaut, a manufacturer of industrial chocolate. This move triggered his entrepreneurial instincts. Klaus Jacobs sensed that the chocolate industry worldwide was ripe for consolidation, and acted decisively. In 1996 he merged the Belgian company Callebaut with the French company Cacao Barry. This was more than a merger of two prominent chocolate companies, each with a long tradition in the same business. It was a union that brought together two mutually reinforcing sets of expertise: Klaus Jacobs blended Cacao Barry’s experience in the sourcing and initial processing of cocoa beans with the competency of Callebaut in the manufacturing and marketing of chocolate products. Barry Callebaut was created – a new, global company that spanned the entire value chain, from cocoa beans to finished chocolate products. And Klaus Jacobs looked even further into the future. He anticipated that large, globally active manufacturers of branded products would look to outsource more and more of their chocolate production processes. (Source: FY08 annual report.)

Consumer confusion, 1998-2009

After the IPO in 1998, BC took a wrong turning by moving into the consumer business in competition with their own customers. They acquired Stollwerck of Germany in August 2002 for a CHF256m enterprise value, plus an initial CHF80m restructuring provision on top. The goal was to grow in Germany and in supermarket private label chocolate bars. And in September 2003 they acquired Brach’s Confections of the US from the Jacobs family for CHF23m plus restructuring costs. The thesis once again was to use direct relationships with US retailers to sell private label chocolate. But Brach’s mainly sold sugar candy, not chocolate, and was a poor fit.

After years of losses and distractions, BC sold Brach’s in 2007 for a nominal sum. (It is now part of Ferrero.) In September 2009 BC announced the strategic decision to exit the consumer business. The sale of Stollwerck for CHF132m to Sweet Products / Baronie of Belgium was finally completed in July 2011.

Mega outsourcing contracts from 2007 and on

In 2007 BC’s outsourcing strategy took off. They announced major contracts to supply liquid chocolate to Nestle in Europe (43,000 tonnes per annum), Cadbury’s in Poland (30,000 tonnes) and Hershey in the US and Mexico (80,000 tonnes), as well as to Morinaga of Japan (9,000 tonnes). This set the pattern for BC’s significant volume growth in the following 15 years, as they became by far the #1 outsourcer to the world’s top chocolate users, as well as mid-sized regional players.

Contracts typically run for 8-10 years, with binding volume commitments and price pass-through arrangements that make them cocoa-price-agnostic. BC is sometimes happy to buy a customer’s captive chocolate factory or to construct a new factory as part of a new multiyear outsourcing contract.

The ramping up of major outsourcing contracts was the making of BC. The change in customer concentration illustrates their success. Back in FY07, the top 15 customers made up 20% of group sales, or CHF820m. By FY15, the top 15 customers represented 39% of sales. Today, the biggest single customer alone represents 10% of sales, or more than all 15 top customers contributed back in FY07.

By 2023, BC boasted outsourcing contracts with six of the world’s top eight global FMCGs. However, in each case they supply only a minority of the total volume, with most chocolate still manufactured in-house. In principle, this allows plenty of further headroom for growth. See chart below from the November 2023 Capital Markets Day.

(For those curious about the logistics of supplying liquid chocolate, there are two options. It can be piped in from a co-located plant, as is the case with BC’s plant in Monterrey, Mexico which sits next door to Hershey’s plant. But in most cases it is trucked in liquid form, in special heated tankers that keep the chocolate at the optimal 48-60 degrees Celsius during transport. BC’s tanker partner is Sitra of Belgium. Three daily deliveries by their 26-tonne tankers would handle a 30kt annual contract.)

Salmonella and stagnation, 2022 to date

On June 30 2022, BC announced the discovery of salmonella in their flagship plant in Wieze, Belgium, which is the historic Callebaut site and the world’s largest chocolate factory with 350kt of production.

The cause was contaminated lecithin from a supplier in Hungary. (Lecithin is the soy product that helps the cocoa liquor and cocoa butter to blend smoothly.)

BC’s response to the crisis was exemplary. They detected the contamination early and ensured that no infected product entered the retail food chain, so no consumer was harmed. (This was in sharp contrast to a separate salmonella contamination incident at Ferrero’s factory, coincidentally also in Belgium and earlier in 2022. In Ferrero’s case, hundreds of people became sick from the bacteria around the world as a result of Kinder chocolate.)

Nonetheless, the incident was a disaster for BC’s reputation as a reliable outsourcing partner. Deep cleaning and disinfection took three months, interrupting deliveries to customers. BC took a direct P&L charge of CHF84m. Far more important is the possible negative impact on long-term growth, as BC’s current and potential outsourcing customers may decide to split contracts between two partners rather than outsource solely to BC.

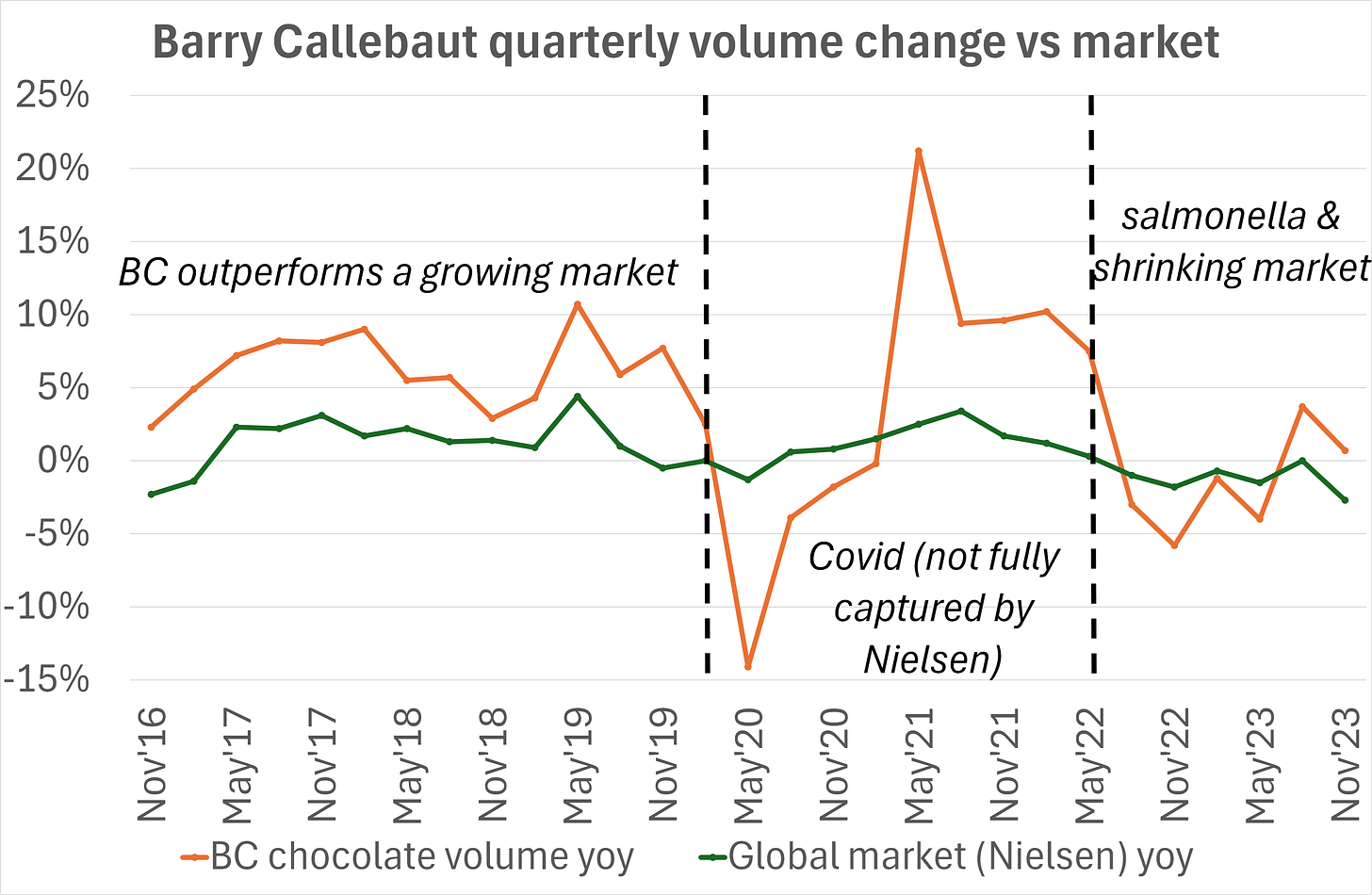

The salmonella incident coincided with a global slowdown in chocolate volumes, presumably impacted by inflation. My chart below shows that prior to 2020, BC was growing chocolate volumes at a mid to high single digit rate. This was exciting enough to justify a NTM P/E ratio of 25-30x. Since mid 2022 and the salmonella incident, BC has seen flattish volumes and the market has been in negative territory. The stock has de-rated to 18x P/E.

Ownership, governance and management

Klaus Jacobs retained 70% ownership of BC after IPO. His family maintained majority control via their charitable foundation until November 2019 and April 2021, when two well-timed 10% placements at high prices took them down to the 35% stake they hold today. See my chart below.

Despite cutting its stake to a minority position, the Jacobs foundation still has status as the ‘reference shareholder’ and maintains de facto control of the board, management appointments and strategy.

Antoine de Saint-Affrique was CEO for six years from 2015 to 2021, an external appointment from Unilever. His spell at BC was a success, as we saw above with the strong volume growth and soaring stock rating. In 2021 he was poached to lead the far bigger Danone, where he remains in charge today.

To replace Saint-Affrique, the board promoted Peter Boone to CEO as an internal appointment after nine years with the company. His background prior to BC was also Unilever, so the appointment represented continuity in every way.

Unfortunately for Boone, the Wieze salmonella incident struck in June 2022, coinciding with the chocolate market downturn. The board acted decisively and sacked Boone in April 2023. They replaced him with Peter Feld. (Just to underline who is in charge, the Jacobs family first hired Feld to their own foundation in February 2023, presumably giving them two months to assess him and brief him before setting him to work at BC in April.)

New CEO Peter Feld – likely to be highly disruptive

Peter Feld is a turnaround specialist with a private equity background. His early career was as an FMCG journeyman at P&G, Johnson & Johnson and Beiersdorf. Then his two prior substantive CEO roles were at KKR-owned Swiss professional coffee machine maker WMF (from 2013 to 2016) and at KKR-owned German market research firm GfK (from 2017 to 2022). In both cases he executed turnarounds before the businesses were sold on to new owners. Listed French appliance maker SEB bought WMF in 2016 (and have been delighted with subsequent performance), and Advent International led the merger of GfK with their NielsenIQ.

Both WMF and GfK were unlisted during Feld’s leadership, but KKR seemed satisfied with his performance. It is interesting to look at some publicly available details:

· Feld’s tenure at WMF grew EBITDA from €100m in 2012 to €140m in 2016, on sales that were little changed. KKR netted a 3.4 times gross money multiple from the exit and generated an internal rate of return of 40%. [Source]

· GfK’s valedictory press release from 2022 describes Feld’s “major restructuring” that made the company “highly profitable”. GfK had 13,000 employees in 2016 but just 8,100 by 2021.

BC Next Level – 19% headcount reduction

At Barry Callebaut, Feld was evidently hired with a mandate for radical change. He first unveiled a brutal restructuring plan at the start of September 2023, just five months after he joined. The plan, called BC Next Level, projects CHF250m of annual savings, equivalent to 15% of the cost base, after spending CHF500m in one-off costs and investments. The stated goal is 4-5% volume growth and a 10% EBIT margin ambition. The latter would imply 25% upside to profits if achieved, given BC has never exceeded an 8% margin to date.

Discussions on redundancies were started with works councils. In a February 2024 press interview, Feld spelt out that 2,500 jobs could be cut, or 19% of the workforce. A number of factories will be closed, and others upgraded to modern standards.

Feld lost no time in reshuffling the Executive Committee. He cut it from nine to six members, and brought in three new personal appointees, giving a 4-2 majority of outsiders – effectively a hostile takeover. The new CFO is Peter Vanneste. He comes from Ontex, the struggling Belgian diaper maker. The new Chief People Officer is Jutta Suchanek. She worked with Feld at both WMF and GfK, and is presumably a trusted lieutenant in executing redundancies in the continental European context. Clemens Woehrle overlapped with Feld at both Beiersdorf and WMF. His official title at BC is Chief Customer Supply & Development Officer, but he can best be understood as the de facto COO, with particular responsibility for reshaping the manufacturing network and overseeing plant closures and reorganisations.

Overall, BC Next Level is surprisingly radical, given most investors were complacently satisfied with the company in its existing form. We can infer that the Jacobs foundation, which already sold a 20% stake at high prices, is highly motivated to boost profits and the share price, perhaps with a further reduction or full exit in mind.

When BC Next Level was announced, the cocoa price stood at below £3,000. While this seemed high at the time, it is nothing compared to today’s £8,000 level. In this sense, the timing and depth of BC Next Level were fortuitous. Whatever the impact of the cocoa price spike, shareholders will welcome the fact that major offsetting cost-cutting actions are already in hand.

Cocoa price spike

From 2000 to January 2023, the benchmark London cocoa price was highly volatile, ranging from £500 to £2,500 per tonne. Year-on-year spikes of +60% and plunges of -40% were commonplace. See the price chart below.

Throughout these years, Barry Callebaut often discussed the challenges of managing such price volatility. Thanks to effective contractual pass-through mechanisms on the large contract side, and pricing power with timely price list revisions on the Gourmet side, they did a great job of minimising any P&L impact. Working capital was the key challenge, with high prices locking up more cash in cocoa bean inventory.

Then in the last twelve months, the cocoa price went vertical. Below is the same chart including the latest price action. The spike to over £8,000 per tonne redraws the y axis and makes all prior history look flat.

Zooming in on the last year alone, the price went particularly crazy in the nine weeks since February, doubling again in this period.

Causes of the cocoa price spike

The cocoa price spike has caught the popular imagination, and has been widely discussed in the financial press. A recent Odd Lots episode provides a good summary.

Very briefly, the price has risen due to an expected supply deficit of as much as 500kt or 10% of global demand. The multiple causes of the deficit are said to include:

· poor weather in West Africa over the last year, including both severe rain and drought at the wrong times;

· worse black pod disease and swollen-shoot virus than usual;

· poor and underpaid small farmers who lack the means or incentive to boost their yields;

· due to government-set prices for farmers in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana that are far below market price. (The governments may now finally pass on a price increase to farmers.)

· The five-year tree maturity cycle means a time lag from any new planting response.

· Non-traditional source countries in Latin America and Asia will increase their supply but from a very low base, not moving the needle much initially.

The most recent spike in the futures market may also reflect a self-reinforcing financial move, as hedging participants are forced to close out short positions due to prohibitive collateral requirements.

An additional complicating factor is a new EU regulation designed to prevent deforestation, which is due to kick in at the end of 2024. According to Bloomberg, “every shipment — in bags or in bulk — will have to list the GPS coordinates of the farms where the cocoa was grown, and that information needs to be uploaded into an EU database. […] If the EU learns that a shipment broke the law, the penalties include fines, confiscation or a temporary ban on trading in the bloc.”

The regulation may disrupt the market in unpredictable ways. A two-tier market could develop, with a much higher price for traceable EU beans and a lower price for non-compliant beans. Farmers in West Africa may be unable to expand their acreage as they normally would – which is of course the intent of the regulation. And existing commercial contracts between cocoa suppliers like BC and large customers like Mondelez and Nestle could be contentious, if the two sides disagree on how to apportion the additional cost of sourcing EU-compliant beans. Finally, BC and other industry players are still lobbying the EU to defer the regulation start date, which creates extra uncertainty one way or the other.

Impact on Barry Callebaut

How will the completely unprecedented price spike impact impact Barry Callebaut? As yet the answer is unknown.

· Back on January 24 2024, when the price had reached an already record-breaking £3,793 per tonne, BC commented in their Q1 sales update.

· At that time they reiterated guidance for flat volumes and EBIT for the full year to August.

· They announced three new debt financing measures to add CHF825m of headroom, in response to the then expected cocoa price impact on working capital requirements.

Since then, the cocoa price has more than doubled again. BC is due to publish its half year report on Wednesday April 10, in two days’ time. All eyes will be on their comments regarding any impacts on volumes and EBIT, as well as the update on working capital requirements and financing capacity.

At a minimum, higher debt levels will have a negative impact on BC’s interest expense and EPS. An extra CHF50m run-rate of interest cost would reduce PBT by c.10%. I factor this into my base case.

A possible profit warning on volumes and EBIT could reset earnings down by up to an additional 20%, in my estimate. I adopt a cumulative 30% downgrade as my downside scenario.

As for wider industry impacts, some hits to volumes and profits seem inevitable. So far:

· Fuji Oil of Japan announced the closure of its Blommer Chicago chocolate factory two weeks ago, as well as downsizing its cocoa processing business, both in response to chronic losses by Blommer. This tangible reduction in capacity by a weaker player is clearly welcome for BC, which is also planning closures of its own.

· Olam of Singapore wants to spin off its ‘ofi’ cocoa, coffee and nuts ingredients business in a London IPO. However the cocoa bean price spike will delay its plans.

· The $570m listed trader Amsterdam Commodities announced hedging-related losses in its organic cocoa business, along with a change of CEO. (Consensus cut estimates by 18%.)

· Hershey warned in February that profits would be flat in 2024 as price increases cause a negative volume response. (The consensus downgrade was only 4%.)

· Mondelez spoke bullishly about their expectations to hike their chocolate prices enough to cover cocoa costs, without much impact on volumes. However, those comments were made at the end of January, when the cocoa price was lower than today.

“What we've seen in the past year is a strong price increase of 12% to 15% in Europe in chocolate with a very limited 0 to 0.5% effect on volume. And so that shows that the elasticity is very low. We think that it's driven because of strong brand loyalty.” (Source: Mondelez CEO, Q4’23 conference call, Jan 30 2024)

Chocolate demand

Global chocolate volume has historically grown steadily and in line with GDP. Total consumption roughly doubled over the last thirty years.

However, since mid 2022 volumes have been shrinking in the developed markets that make up the large majority of BC’s business today.

The key cause is probably inflation and negative elasticity to already-implemented price hikes. This would be short-term bearish, given that chocolate retail prices are about to rise much further, but long-term bullish, because there would be no change to the assumption of gradual ongoing volume expansion as the normal state of affairs when prices are not rising.

A much more bearish view would be that chocolate consumption per capita has peaked. This is sometimes linked to the growth of GLP-1 weight loss drugs. In my view any such thesis is highly speculative, and not something I’d invest behind. Note that volumes have fallen in Europe, where GLP-1s are as yet unknown, but inflation has been rampant.

A separate matter is that legacy FMCG brands may be disrupted by newcomers. In principle this is neutral for BC, which can cater to new entrants.

As a case study, Tony Chocolonely is a favourite “new” customer of BC’s. It is trendy and fast-growing, and it relies on BC for 100% of its ethical liquid chocolate. However, Tony Chocolonely (which is majority owned by the aristocratic Belgian Spoelberch family that made a fortune from AB InBev) reached just €150m in sales in FY23, which likely translates into less than €50m of revenue for BC. They would need dozens of Tony-sized fast-growing customers to make any difference to their overall growth rate.

In regional terms, BC’s current sales split is 45% EMEA, 27% Americas, just 7% Asia Pacific and 21% Global Cocoa (upstream supply of cocoa products not subject to regional allocation).

BC has big hopes to benefit from increasing per capita consumption of chocolate in Asian countries such as China and India. BC’s new President for Asia, Vamsi Thati, is the former Coca-Cola Company head of greater China, as well as an Indian national. He recognises that if Asian countries do grow to become meaningful consumers, this will likely be compound chocolate rather than “real” chocolate – i.e. made with vegetable fats rather than cocoa butter. BC has historically been weaker in compound chocolate and is attempting to rectify that.

Financial profile

BC has a good track record of profitable growth. In Swiss francs it has grown revenues by 5.6% per year since 2000, while keeping the margin generally steady in the 6-8% range – see chart.

The revenue growth has broadly tracked volume growth of 4.9% per annum over the same period. See chart.

The Swiss franc has been the strongest major currency in the world over this period. BC’s revenue growth would look much more impressive if expressed in local currency terms such as Euros, British pounds or Japanese yen. The effective FX chart below suggests a c.20% FX headwind.

The growth has by no means been purely organic. A big acquisition and many bolt-ons contributed.

The main acquisition in the period was the cocoa business of Petra Foods of Singapore (now Delfi) in June 2013 for CHF821m. This added seven cocoa factories and 1,700 extra staff to BC’s network, and significantly increased its scale in upstream cocoa bean grinding operations. (The acquisition was messy. The initial press release claimed the Petra unit was a CHF1.1bn revenue business in 2011, but in the year to Aug’13 it turned over just CHF854m, and in the first full year of BC’s ownership sales were just CHF635m. BC withheld $90m from the final consideration and won an extra $39m refund from Petra in the dispute resolution process.)

BC also spent a cumulative total of around CHF500m on bolt-on acquisitions throughout the period from 2000 to 2023. They bought many niche firms for what became known as the Specialties and Decorations business, as well as some factories in support of large outsourcing contracts.

Capital expenditure has been high and above depreciation every year since FY07 (see chart below), as BC has invested to support the outsourcing-led volume growth.

Return on invested capital has suffered since FY13 due to the costly Petra acquisition, but has remained at a respectable level in the low double-digits, well above the WACC. Crucially, this demonstrates that BC has been adding value with its capex-led growth strategy, despite the thin margins attached to large outsourcing contracts.

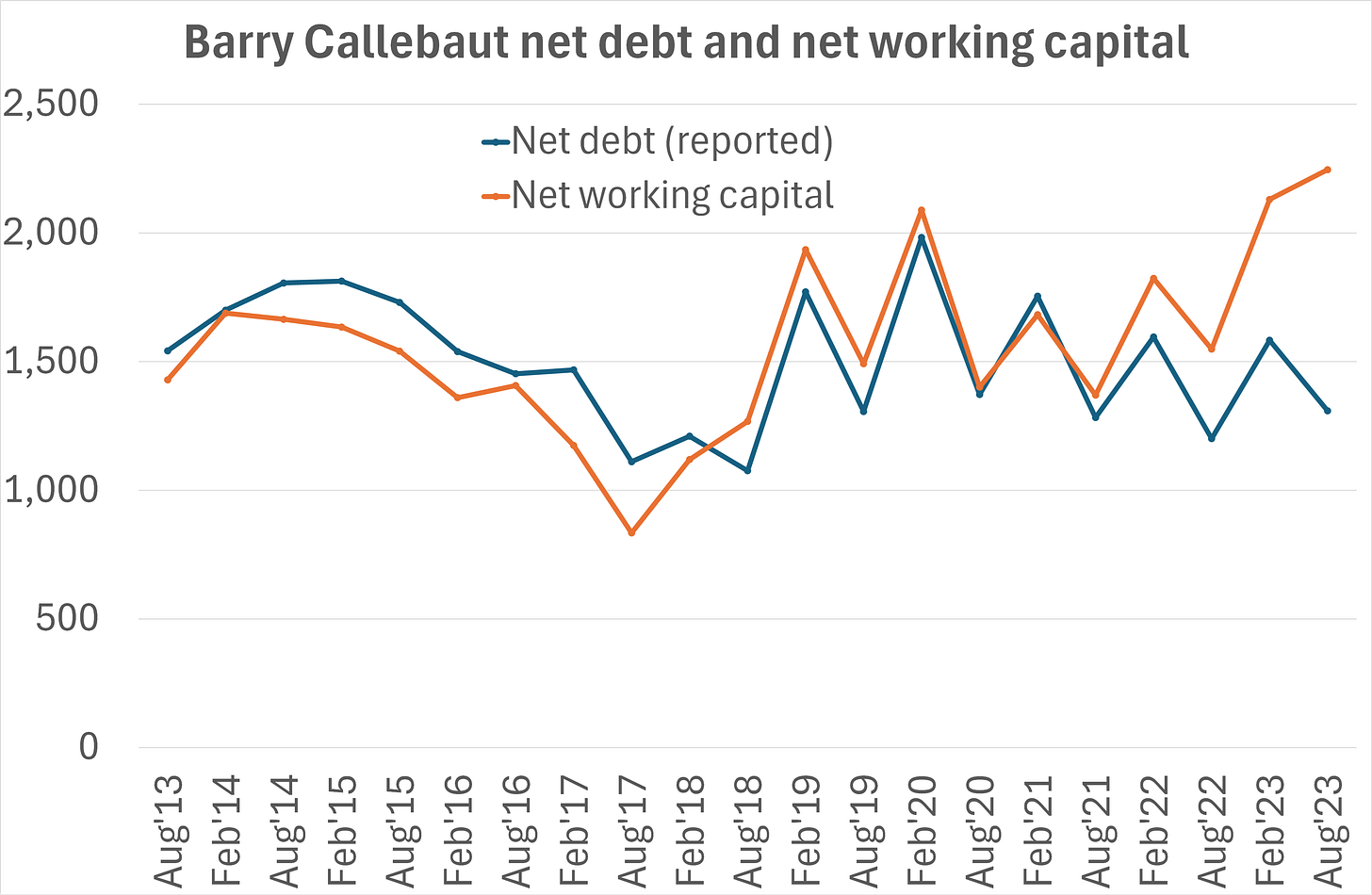

The balance sheet requires a closer look. Net debt on a reported basis is modest. It stood at CHF1,366m at Aug’23, for a 1.9x net debt to EBITDA ratio. My chart below shows that net debt has generally tracked and funded the net working capital position.

From the above chart, the divergence in Aug’23 between net debt (which stayed low) and net working capital (which spiked) is notable.

The explanation is found in BC’s derivatives book, which it uses to hedge its cocoa bean positions. My chart below shows that BC’s net derivative position was negative to the tune of CHF603m in August 2023, by far the biggest negative position seen in recent times. We must presume that BC’s hedging is working as intended, and losses on derivatives will be offset by gains in BC’s physical business. This is to be confirmed on Wednesday.

Seasonality is significant for BC’s balance sheet. The August balance sheet date is the low point in the year for working capital and net debt. Most cocoa beans are purchased in the main harvest, which lasts from October to March. The chart below adds in the six-monthly balance sheet position to show some of the seasonality.

The adoption of IFRS 15, Revenue from Contracts with Customers from FY19, revealed the debt seasonality, which was previously hidden, due to changed accounting treatment for “structured solutions that the Group had entered into for the management of working capital of exchange traded commodities (namely cocoa beans)”.

Where we suspect that true daily average net debt is significantly higher than the balance sheet position, a useful cross-check is to look at cash interest expense and the implied interest rate vs the stated average debt position. For BC, this calculation shows an implied interest rate of around 6-8% (see chart below), a little higher than one would expect. This suggests daily average net debt is indeed higher than the twice-yearly disclosed balance sheet positions.

Another balance sheet consideration is BC’s use of ‘asset-backed securitization programs’, i.e. factoring or invoice discounting. My chart below shows the balance in the program (CHF415m at Aug’23) and the associated interest expense. This was a very cheap source of funding before the ECB hiked its rates. The balance would need to be added back to get to the true underlying level of net debt.

The credit ratings agencies do add back the factoring balance to BC’s stated net debt figure, as well as the lease liabilities and small pension deficit. Moody’s currently rates BC as Baa3, the lowest investment grade rating. S&P rates BC as BBB, which is one notch higher. These ratings could presumably be at risk of downgrade given the immediate prospect of much higher working capital and debt.

I note that BC spent much of the previous 25 years operating with a sub-investment grade rating – e.g. it issued junk-rated bonds in 2016 at a 2.5% yield. So another potential spell with a junk rating need not be too much of a worry.

BC’s dividend policy is another balance sheet consideration. Since FY12 BC has consistently adhered to a 35-40% dividend payout ratio – see chart. However, the new CEO has committed within the BC Next Level plan to maintain the dividend at the FY23 level of CHF29 per share, regardless of a likely fall in earnings during the dreaded ‘transition period’.

This could prove to be a mistake. The consensus estimate for FY24 EPS is currently CHF69.45, implying a 42% payout ratio. At a minimum, the higher interest cost associated with the additional cocoa inventory is not yet factored into consensus, and will put downward pressure on EPS. It is also possible that BC will announce a major profit warning with lower volumes and EBIT, as a result of the exceptional cocoa price impacting customer demand.

If it warns, then BC will face the unpalatable choice of whether to cut the dividend (undermining the new CEO’s credibility), or to maintain the CHF159m payout at a time when its balance sheet would come under serious pressure.

Estimates and valuation

My estimates are shown below, with explanations underneath.

In FY24 and FY25, revenue will spike up to record levels due to much higher cocoa prices. By how much is hard to predict, but also not important. What is clear is that profits will certainly not mechanically spike up by a comparable amount. Instead, if BC is lucky it will be able to hold EBIT flat in constant currency terms in FY24, as per the current guidance. A headwind from the strong CHF means a fall in EBIT in reported terms is on the cards even before any possible profit warning.

The percentage EBIT margin also loses meaning during the period of spiking cocoa prices. My estimates imply the lowest EBIT margin in a decade for FY24E and FY25E, which recovers to 7.5% in FY26E due to an assumed moderation of the cocoa price as well as some benefits from the BC Next Level cost cuts. New CEO Peter Feld’s suggested 10% margin target looks way out of reach, but this lacked credibility in any case given the link between cocoa prices and margins.

My interest line factors in much higher expected funding costs for the costly bean inventory in FY24E and FY25E, with this unwinding in FY26E.

My base case EPS estimates sit 11-12% below the consensus midpoint, but in line with the lower end of the range. (It is a positive sign that the range of consensus estimates is extremely wide, meaning investors should already be aware of the wide range of possible outcomes.)

The valuation is 13.8x P/E in August 2026 on my base case estimates. I find this highly attractive given that the outlook from there would be for high single digit growth. Upside surprise is possible if the CEO’s cost-cutting ambitions can be delivered more fully than I project.

For reference, the chart below shows the historic valuation in NTM P/E terms. The >30x rating at peak was clearly over-egged, and should not be anchored to. But I find the current rating of 17.7x a reasonably sensible trough estimate to be attractive.

As discussed above, my downside scenario would envisage a profit warning on volumes and EBIT, which would take FY24E and FY25E earnings another 20% lower than in my base case. The stock would react negatively and rebase by a similar amount, but should then still have a similar mid-term upside profile from that point, given that the story would not be fundamentally broken.

Annex: market share and brief peer profiles

BC has an approximately 20% market share in all three areas of Gourmet, cocoa sourcing and chocolate-making: see charts below. Gourmet is fragmented while Cocoa is relatively consolidated.

The key peers in upstream Cocoa are the following.

· Cargill, the giant commodity trading house which is the biggest privately held US company by revenue. Its financial performance and balance sheet are both strong, according to the credit ratings agencies. No information about the performance of its cocoa business is disclosed. Cargill matches BC in offering liquid chocolate outsourcing contracts, as well as cocoa grinding.

· Olam’s ofi business, which bought ADM’s cocoa business in 2015. As noted above, Olam intends to list ofi separately in London as a spin-off, but the timing is delayed. ofi handles cocoa, coffee, nuts, spices and dairy, with USD11.5bn of revenue and $615m of EBIT in 2023. Its ROIC is disclosed at around 7%, which is not too impressive.

· Cemoi is a French business which is part of privately held Belgian group Baronie / Sweet Products. It has a long history of sourcing cocoa in West Africa, and is cited as one of the Big Four alongside BC, Cargill and Olam.

· Ecom Trading of Switzerland (owned by the Spanish Esteve family) is another major cocoa trader. They acquired Armajaro’s business in 2013.

· Fuji Oil’s Blommer has upstream cocoa sourcing and trading activities, but Fuji is planning to downsize these significantly.

· Guan Chong (GUAN:MK) is a listed $630m Malaysian cocoa and chocolate producer. It has a mediocre financial profile of single-digit returns on capital. It has been expanding globally, for example it recently opened a new liquid chocolate factory in Suffolk, UK.

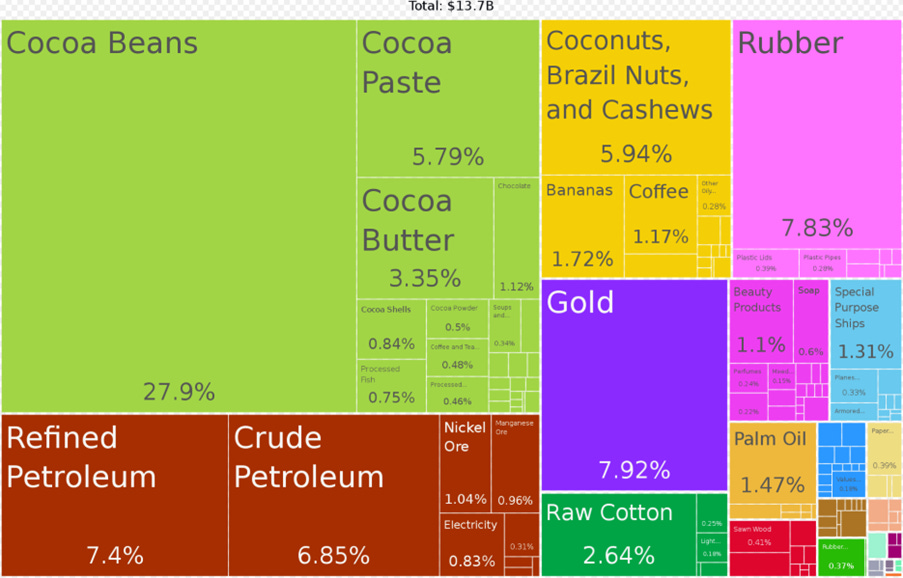

For reference, Cote d’Ivoire’s economy is in relatively good shape. It has been one of the wealthier and faster-growing economies of West Africa since the end of the civil war in 2011. The importance of cocoa to the country’s overall exports cannot be over-stated – see diagram below.

great article, I started a position in BC about month ago and after all my research I still learnt new things from reading your article.

BTW I like the way your articles are structured starting with the thesis followed by a description of the company as a whole. It really irritates me when you sometimes read a thesis and there isn't much information on what the company actually does besides what you've read in the thesis.

Thanks for the in depth write-up!

Jacobs selling down their stake and putting in Peter Feld does make you wonder how long they will still be owners, no?