Borregaard – an economic castle protected by an unbreachable moat

(BRG.OL, $1.8bn market cap, $1.0m ADVT, 100% free float)

Many thanks to Alastair Kendall for suggesting in the comments to my Croda write-up that I take a fresh look at Borregaard.

An hour’s drive south of Oslo is the small town of Sarpsborg. Here you can find Borregaard’s biorefinery. First established as a cellulose factory 125 years ago, it has been developed into a highly efficient network of twenty connected factories that process Norway spruce wood chips into 800 specialty lignin and cellulose products.

Borregaard has been listed since October 2012, when it was separated from the Orkla consumer goods conglomerate. The first twelve years of independence have been promising, with an 8% profit CAGR sustained from 2011 to 2023, as shown below.

A long-serving management team has pursued a strategy of profitable specialisation since 1991, and this still has much further to run. Consistent reinvestment into the Sarpsborg site has boosted productivity and flexibility, with more to come.

Borregaard’s wood-derived products are inherently sustainable alternatives to petrochemicals. In certain niches this wins favour from customers and regulators, driving higher prices.

Crucially, Borregaard is one of a kind. None of its global competitors has the same history, raw material configuration or competencies. Surprisingly high barriers to entry should enable Borregaard to sustain its mid-teens ROIC for many years to come, as less advantaged producers struggle and fall by the wayside.

Valuation is attractive at 20x 2025E earnings. The correct benchmark is not other chemicals stocks, but other businesses with sustainable competitive advantages and self-directed growth.

Margins are close to a peak level, which would normally ring alarm bells. But in fact a lot has gone wrong for Borregaard in recent years. I take this as reassuring evidence that current margins may be sustainable or even have upside.

I have started a position in Borregaard at around the current price. Feedback is welcome, as always.

Background and management

A cellulose and paper mill was first built in Sarpsborg in 1889 by the Kellner Partington Paper Pulp Company, a British investor that manufactured cellulose where the raw materials were located and sent the cellulose to England for processing into paper. By 1895 Borregaard already accounted for a third of Norway's total cellulose production, and in 1909 Borregaard was Norway's largest industrial workplace. From 1918 the business was sold into Norwegian ownership. Already from the second world war onwards, production was widened from cellulose and paper to a wide range of chemical products.

In 1986 Orkla merged with Borregaard. Soon after, the present management team joined. As shown below, the entire team has unusually long service with Borregaard.

The CEO, Per Sørlie, spoke at the recent Capital Markets Day of the culture that he has deliberately inculcated since 1990. Borregaard is market-oriented, innovative and change-oriented. He developed a B2B academy for all managers, not just sales and marketing staff, in order to make everyone more market-oriented and commercial. The concept of value-in-use of their products runs deep at Borregaard, rather than cost-plus pricing.

Borregaard’s core values are sustainability, long-term perspective and integrity. Sustainability is defined to include financial as well as environmental sustainability! The CEO describes having the epiphany early on that while technically it is possible to make everything from wood that you can make from oil, they will be selective about what they choose to produce that will make the most money.

How it works

Borregaard’s basic raw material is one million solid cubic metres of spruce per year. Wood is sourced from Norway (80%) and Sweden (20%), and is all certified as sustainable. Borregaard is able to purchase wood chips that are a sidestream from the sawmill industry.

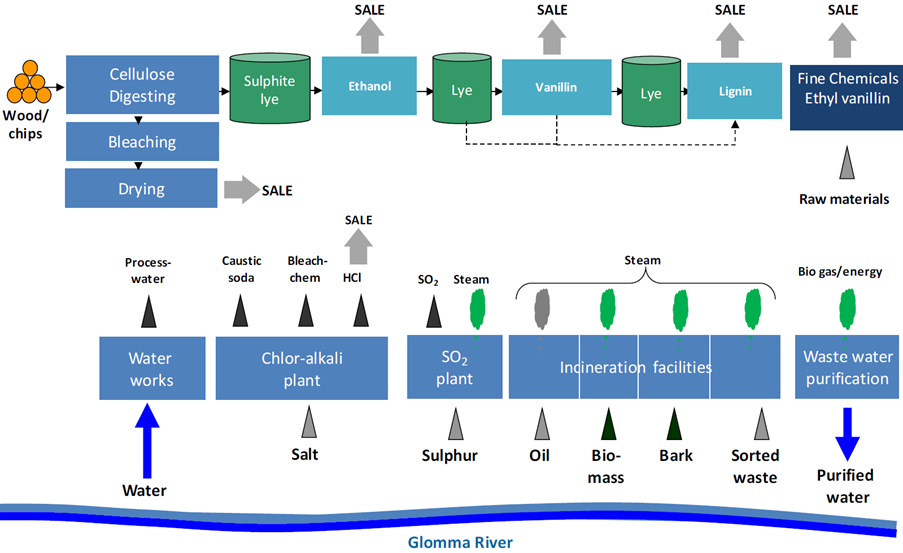

At the Sarpsborg refinery, Borregaard cooks the wood chips in the digester house in acid at high temperature and high pressure. This separates the cellulose fibres from the lignin (binding material) and sugar (which is fermented to produce bioethanol). Caustic soda is a key input, which Borregaard produces internally for the majority of its needs. See diagram below.

After the cellulose has been separated from the lignin, each stream is subjected to several more chemical and physical modification steps. These differ depending on the exact product and customer specification in question. Production is organised according to a six to eight week schedule, in order to cycle through the c.800 different products as efficiently as possible.

“In our Sarpsborg refinery, we are over a cycle of 6 to 8 weeks, doing a wide range of smaller-scale products in a very efficient manner. I mean the challenge is, of course, that complexity could create costs. But since we have educated our people, we have automated our plants and so on, we are able to carry out this without experiencing kind of loss in introducing that complexity in our plant.” [Source: September 2022 CMD transcript]

Market positions

Borregaard is unique in producing high value specialties from both cellulose and lignin in an integrated model. This underpins its strong financial return, which is counterintuitive given what ought to be an uncompetitive cost base. (Salaries in Norway are higher than almost anywhere else.)

The diagram below shows the high utilisation that Borregaard gets from the wood. It is by far the global number one in lignin products, and also a strong niche player in specialty cellulose. For cellulose rivals, lignin is mainly incinerated for process energy, or even a waste product.

For lignin, Borregaard is the dominant global #1. By volume, its market share is estimated at 35-40%, as shown in the diagram below. (The #2 player, Domsjø of Sweden, was acquired by Aditya Birla in spring 2011.)

By value, Borregaard has an even higher 60-70% lignin market share, because it is uniquely competent at creating and marketing high-value niche products that its rivals cannot match.

Meanwhile, in specialty cellulose, Borregaard was merely the fifth largest producer by volume in 2022, as shown in the diagram below.

Borregaard’s softwood feedstock and sulphite pulping process is uniquely well suited to producing the most valuable cellulose products with the highest viscosity and purity. (RYAM’s Tartas plant in France is the only one in the world with a similar configuration, yet it has a poor financial track record, with a €10.5m loss on €110m sales in 2023.)

This is the key barrier to entry that ensures Borregaard’s castle cannot be attacked. Most pulp plants globally use the kraft process, as it is better suited for paper production. Yet it cannot be used for high quality specialty cellulose products, nor does it produce lignins suitable for biopolymer use.

Even other sulphite mills use different chemicals in the process: calcium, sodium, magnesium or ammonium can be used. RYAM’s Tartas plant uses ammonium. Only Borregaard uses a calcium sulphite process with softwood, which is best suited to making the most advanced lignin products.

I believe that the near-impregnability of Borregaard’s moat is not widely understood by investors who may have looked casually at the stock. If this is the case, then Borregaard will be able to continue alone along its specialisation strategy, without fear of direct competition in the most advanced grades and products. That could lead margins to surprise on the upside over time.

BioSolutions (lignin and biovanillin)

The BioSolutions segment comprises Borregaard’s lignin and biovanillin businesses. This segment contributed 55% of total sales and 52% of EBITA in 2023.

Borregaard’s specialisation has been relentless in this segment, yet still has far to run. The total volume of lignin product sold has actually fallen over the last 12 years, yet revenue has grown significantly over the same period. Lower-value products in construction and industrial applications have been gradually edged out in favour of higher-value specialties, as illustrated below.

All of the above requires further explanation.

The overall volume reduction has been from necessity, not choice. Borregaard produces lignin products not only at Sarpsborg, but also at a global network of factories built adjacent to pulp mills that utilise the sulphite process, in order to take advantage of their streams of lignin raw material that the operators would otherwise lack the know-how to exploit. However, this leaves Borregaard at the mercy of the pulp operator’s overall fortunes. And in fact three pulp partners fell into bankruptcy or switched process in a way that terminated Borregaard’s raw material supply.

Specifically, Borregaard’s 50:50 lignin JV with Sappi in South Africa was mothballed in 2020 due to Sappi’s closure of the adjacent pulp mill. Sappi then decided to convert the pulp mill from calcium sulphite, the source of lignin raw material, to magnesium technology which does not supply suitable material. Final liquidation is due to take place this year, with minimal P&L impact.

Similarly, Borregaard had a 60:40 lignin operation with Sniace in Spain, which also lost its local lignin source in 2020 when Sniace’s cellulose business went bankrupt and had to close.

Borregaard also lost supply from Wisconsin when Flambeau River’s Park Falls pulp mill finally closed in Q1 2021.

Borregaard had added 100kt of additional capacity at its Florida JV with RYAM which opened in 2018, but this was more than offset by the 2020-21 volume losses noted above.

Construction-use lignin includes several different products. Concrete admixtures are the biggest by volume, used to prevent settling or clumping. The customers are price-sensitive, and tend to switch between Borregaard’s lignin products and petrochemical-based products like superplasticisers with similar or superior properties. As supply became tighter, Borregaard has therefore deprioritised admixtures in favour of alternative products with higher value-added to the customer and therefore higher selling prices. Construction still accounts for a third of total volumes, meaning the process of gradually donating its capacity to higher-value uses can continue for years if not decades to come.

Industrial-use lignin is a similar story. At over 40% of total volume, this comprises hundreds of products of medium value. There is a relentless process of allowing the customers to compete for the available capacity through the price mechanism.

Specialties are highly specialised applications with the best prices. These currently account for just 25% of total volumes, but contribute 60% of revenue and contribution margin. They include agriculture and lead batteries as two of the more prominent end markets among many others.

In agriculture, Borregaard’s lignin products are used in formulation of fertilisers, pesticides, seed coatings and animal feed. See overview below.

Croda investors will be curious that Borregaard seems to have sailed through the last two years without needing to complain about destocking by the agriculture customers. Management commented on this last year, as below. We can infer that Borregaard is gaining market share and continuing to increase its penetration of the agri sector.

“[W]e have certainly noted that several chemical companies have come out with profit warnings related to the agriculture market. If you look at our situation this year, in total, like we commented also after the second quarter, the volumes sold into agriculture, and we have literally hundreds of products going into agriculture, are quite balanced compared to the last year. Also, I say that the contribution from the agricultural market is better this year than it was last year.” (Source: Q3’23 conference call, October 2023)

For lead acid batteries, Borregaard has near-100% penetration with Vanisperse, its lignin organic expander product that protects the spongy lead structure from deterioration and regulates crystal growth. This market is still in growth to date. There will eventually be a drop-off of lead acid batteries in favour of lithium-ion batteries. Borregaard has patented a dispersant for li-ion batteries that is supposed to offer improved properties and reduced cost. This product is in qualification trials with key potential customers.

Biovanillin is another component of the high value specialties. Borregaard is the sole global producer of vanilla extract from wood. It sells this product to food and fragrance customers at $30-70 per kg, close to two orders of magnitude higher than its other products. However its total yield is just a couple of thousand tonnes per year.

The graphic below shows that this price is a big discount compared to Madagascan pod vanilla. It is also sold at a significant discount to Syensqo’s vanillin derived from ferulic acid from rice bran, as that product can be described on EU labels as “natural flavour”. However, Borregaard’s vanillin still commands a significant premium to vanillin derived from petrochemical feedstock. In addition, Borregaard trades in petrochemical-based vanillin in order to offer a complete range to customers. (Consumers are probably happy not knowing that most cheap vanilla ice cream is petrol-powered!)

Borregaard sees no end to the specialisation process. In 2023 they announced a new green technology platform of next-generation lignin-based products targeting high-end applications such as detergents and laundry, industrial cleaners, water treatment and additional agriculture products. They have committed to a NOK100m investment in a commercial-scale demonstration plant, the first phase of which has just been completed.

The new product is described as enabling Borregaard to compete for the first time against advanced fossil-based alternatives such as polyacrylates. In dishwasher tablets, a 5-8% dose of Borregaard’s LignoBrite can replace polyacrylate as the anti-filming agent to prevent glasses becoming cloudy after repeated wash cycles. This product is initially being launched in Sweden next year with a niche eco brand. If successful, the volume potential would be large.

Overall, the BioSolutions segment is highly diversified, with 2,700 customers, of which the top ten account for less than 30%.

BioMaterials (specialty cellulose)

BioMaterials includes the specialty cellulose portfolio as well as cellulose fibrils. The key customers here are cellulose ethers manufacturers as well as acetates makers.

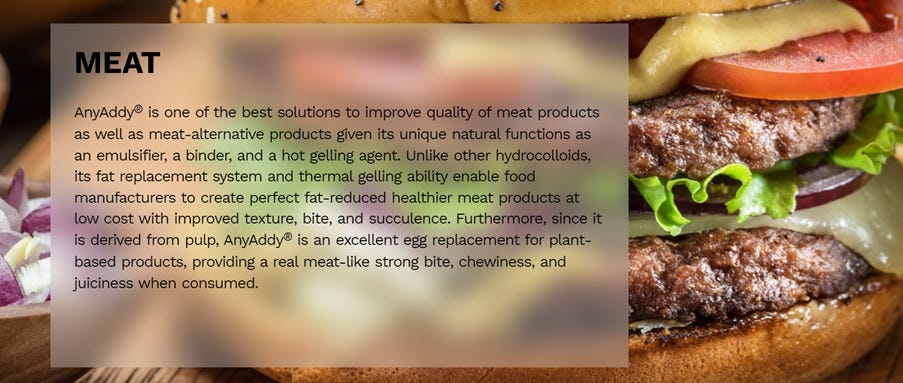

Cellulose ethers are water-soluble polymers, used as an additive to modify rheological (flow) properties of water-based formulations. Water-based paints and modern plant-based burgers are two end-markets. (Both Beyond Meat and Impossible plant-based burgers list Methyl Cellulose as an ingredient.)

The top six cellulose ether producers, all clients of Borregaard’s, are Ashland, Dow, IFF, Shin-Etsu, Lotte and Nouryon (fka AkzoNobel Specialty Chemicals).

Importantly, the specialty cellulose that Borregaard supplies to the ether makers is not a single commodity grade. Instead, each customer has different requirements for purity, viscosity and sheet size. Qualification periods are lengthy, and the barrier to entry is high. Within ethers, the most stringent requirements and the highest value opportunities are for pharma, food and cosmetics. Within ethers, Borregaard is shifting its focus from construction use towards these regulated uses, in order to achieve higher prices.

Acetate tow is used to make cigarette filters, with extremely demanding quality requirements. Celanese, Eastman and Filtrona would be relevant customer names. Historically this application accounted for a significant proportion of specialty cellulose volume, both overall and for Borregaard. Cigarettes are in volume decline, but heat-not-burn products such as IQOS also use acetate tow filters. Over the last 12 years Borregaard has achieved a gradual shift in weight from acetates to ethers.

Beyond ethers and acetates, other cellulose applications for Borregaard include sausage casings, tyre cord for high-speed tyres, and sponges.

Customer concentration in the BioMaterials segment is rather high, with 41% of segment sales to the top three customers, which will be among the acetate and ethers names mentioned above. The relationships have been long-lasting. I don’t foresee any issues, given the highly specialised nature of the products Borregaard supplies.

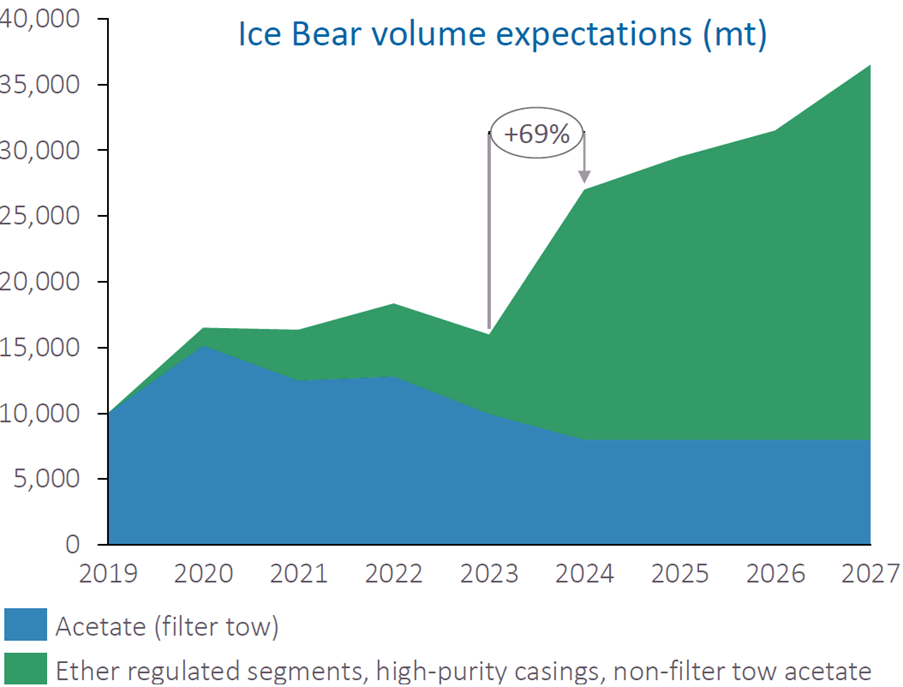

Back in 2015, Borregaard announced an investment into new specialty cellulose grades with ultra-high purity. This project was mysteriously dubbed “Ice Bear”. The name is thought to stand for “innovative caustic extraction”, a variation on cold caustic extraction, although Borregaard itself has not confirmed this. In any case, Ice Bear technology is said to have driven improved sales and pricing in the near decade since it was launched.

The Ice Bear product really came to life a year ago, when Koch’s Georgia-Pacific surprisingly announced the permanent closure of its Foley cellulose plant, with the removal of 100kt from the market at a stroke. This plant had been renowned for high-purity cellulose. Borregaard estimates it has captured 15-20kt from Foley’s closure at high prices, mainly using the Ice Bear technology. The chart below is emblematic of Borregaard’s patient approach in investing steadily into its specialisation strategy.

Another long-term project that has not yet paid off is microfibrillated cellulose, or MFC. This is supposed to be an innovative replacement for petrochemicals in many applications. This distinct product family is sold under the Exilva brand name. The gestation period has been typically lengthy. A pilot plant was in place since 2008. In 2014 Borregaard decided to invest NOK225m in a 1,000 tonne production facility, perhaps swayed by a €25m subsidy from the EU.

Market introduction has disappointed, as conversion of sales prospects to regular customers was poor. Prosaically, the most successful application to date has been corrugated board adhesives, where Borregaard has now accumulated the experience to teach the customers how to benefit from it, leading to quicker and more successful trials.

(I note in passing that the #1 cellulose player, RYAM attempted to invest downstream into Anomera, a startup developing carboxylated Cellulose Nanocrystals in partnership with Croda for the global beauty market. This does not appear to have gone anywhere as yet.)

Fine Chemicals

This segment is effectively “Other” and includes two separate businesses. Borregaard is the largest producer of C3-aminodiols for non-ionic X-ray contrast media. It also produces just over 20 million litres of bioethanol per year, mainly for use in biofuels.

The Fine Chemical segment has produced record profits in recent years, thanks to favourable market conditions for advanced biofuels in several European countries, backed by regulations that require a percentage of biofuel to be blended into all fuels. This tailwind is expected to continue for the foreseeable future, but regulation and / or market pricing could change in the longer term. I conservatively model a fade in segment profits in the years ahead.

Financial results

The proof of the specialisation strategy should be found in average prices and margins. Below is the track record for the lignin business (currently named BioSolutions segment). The continual and drastic increase in average price is remarkable: see chart below.

The sharp decline in volume post 2019 relates to the loss of three overseas sources of lignin raw material in South Africa, Spain and the US, as described above. The loss of that supply was out of Borregaard’s control. It underscored the high value of being fully in control of the main supply from its Sarpsborg refinery. A debottlenecking investment project will add 5-10% to Sarpsborg capacity in the next 2-3 years.

As noted above, only 25% of the volume in Borregaard’s lignin business is currently classified as highly specialised. This means the average price shown above has headroom to continue to climb for many years to come.

The volume and price picture for specialty cellulose (BioMaterials segment) is similar: see below. Volumes in this segment are entirely from Sarpsborg, and are stable over time. The average price in this segment has also shown strong growth.

Unlike for lignins, the cellulose business has already reached 100% specialty by volume, with no commodity grades sold into the textiles business any longer. There are big price differences between different specialty grades, which means the process of improving price-mix and finding higher-value uses can continue.

Margins for the two main segments, and for the group, are shown in the chart below. The group margin has been rising fairly steadily over time, as bigger fluctuations in the segment margins have tended to balance out. In the short term, margins can come under significant pressure from external influences. In the long term, Borregaard’s unique position at the top of the value curve should enable it to adjust prices as necessary to capture its fair share of the high value it provides.

The cost profile is well spread across wood (12%), energy (12%), caustic soda and all other raw materials (24%), distribution costs (12%), payroll (24%) and others (16%). Cost increases in the last five years have been drastic across both wood (still rising) and energy (now falling back). Borregaard has been more than able to pass this onto customers, as shown in the margin picture above.

Borregaard’s business is capital intensive. Operating cash flow is generally strong, subject to working capital fluctuations. Borregaard uses this cash to invest consistently back into its sites, with maintenance and expansion capex separately identified. The chart below shows the bulge associated with Borregaard’s share of the $110m Florida greenfield in 2017-18.

Since 2021, Borregaard has invested in four bio-based start-ups that apply the biorefining concept to kelp / seaweed, coffee grounds and non-water-soluble lignins. Alginor of Norway is the key investment. It is developing a fully integrated business to harvest and refine brown kelp, targeting pharmaceutical and nutraceutical markets. Borregaard has subscribed NOK419m over three rounds for a 35% fully diluted stake. These investments are included in the “expansion capex” totals shown above.

Borregaard tracks its pre-tax ROCE as a key KPI, with a target of above 15% over a business cycle, representing clear value creation above its WACC. As per my chart below, it has exceeded this target in the last ten years, while also steadily investing in projects that can be expected to strengthen and benefit the business in the future.

Currency is a significant factor for Borregaard. For the last eleven years, on a trade-weighted basis, the Norwegian krone has done nothing but weaken. See chart below.

This has undoubtedly been beneficial to Borregaard in aggregate. However, I note that the firm has a substantial rolling USD and EUR hedge book in place, lasting up to 36 months. This has acted to delay the P&L benefit of the most recent krone weakening. 2025 stands to see a significant P&L benefit from the moves that have already taken place, all else equal.

Estimates and valuation

In H1’24, PBT fell back by 13% from the peak level of a year earlier, due to lower prices and higher wood costs in BioMaterials, compared to the exceptionally favourable 2023. H2’24 has easier comps, before the potential for much stronger pricing in 2025. Borregaard typically negotiates prices with customers for the full year or for six months at a time. Fundamentally, 2024’s pricing slate did not reflect the extreme market tightness in specialty cellulose caused by the sudden withdrawal of capacity by both Georgia-Pacific’s plant closure and RYAM’s idling of its Temiscaming plant. This tight market should lead to higher prices in 2025.

Overall, my forecasts, shown below, reflect an 8% CAGR in revenues and earnings for the four years from 2023A to 2027E, driven 6% by price and 2% by volume. This is roughly consistent with the long-term track record, and much slower than the 4-5 years up to 2023. I would hope that my estimates prove conservative. I end up around 10% below the sell side, which is typically optimistic in Norway.

I find the valuation of 20x 2025E P/E to be attractive. The stock got over-heated in 2021, like all quality Nordic names with ESG pretensions. That over-valuation looks to have fully unwound: see below.

While at first glance the stock might still appear expensive when compared to many European chemicals names, as well as pulp and paper-exposed names, I argue that those are not suitable peers for Borregaard. Its long-running and self-driven specialisation strategy gives it a superior growth profile to most peers. It has also proved to be less cyclical than other names in the materials sector.

While Borregaard’s lignin chemicals franchise is unique, Rayonier Advanced Materials (RYAM) is the closest listed peer on the specialty cellulose side. It was spun off in 2014, and acquired Tembec in 2017. At $528m market cap, RYAM has high debt and very low profits. It has struggled due to a lower degree of specialisation than Borregaard, yet a higher cost base than Bracell located in Brazil. (Bracell was HKSE listed until 2016, when it was taken private by Royal Golden Eagle, a privately held, vertically-integrated Singapore-based player with a focus on viscose textile grades.) I couldn’t exclude a cyclical recovery play in RYAM, but in the long term it looks to be at a structural disadvantage to Borregaard.

I would also highlight Lenzing of Austria as a counterexample of a peer with a high technical competence but a failed commercial strategy. Lenzing has put all its eggs in the viscose textiles market, which has left it with the tagline “Master the crisis”.

The ten-year total return of the three stocks is shown below.

I own it too, good company in interesting niches. Exilva could bring large upside but has taken a lot longer than thought.

Very good write-up. The company has been on my watchlist for a long time and the underlying quality seems to be even better than I thought.