I spoke to Campari’s investor relations team in preparing this report. All opinions and estimates are solely my own responsibility. Feedback is welcome as always.

Luca Garavoglia was just 25 years old when his mother appointed him chairman of Campari in 1994. It was a tiny but profitable Italian spirits company, famous solely for its eponymous Campari bitter red aperitif.

Starting in 1995, Garavoglia transformed the business with bold acquisitions and brand-driven organic growth. Still in charge today, his ambition is bigger than ever.

Campari now has over fifty brands. Yet as an investment proposition, there is one brand that matters the most.

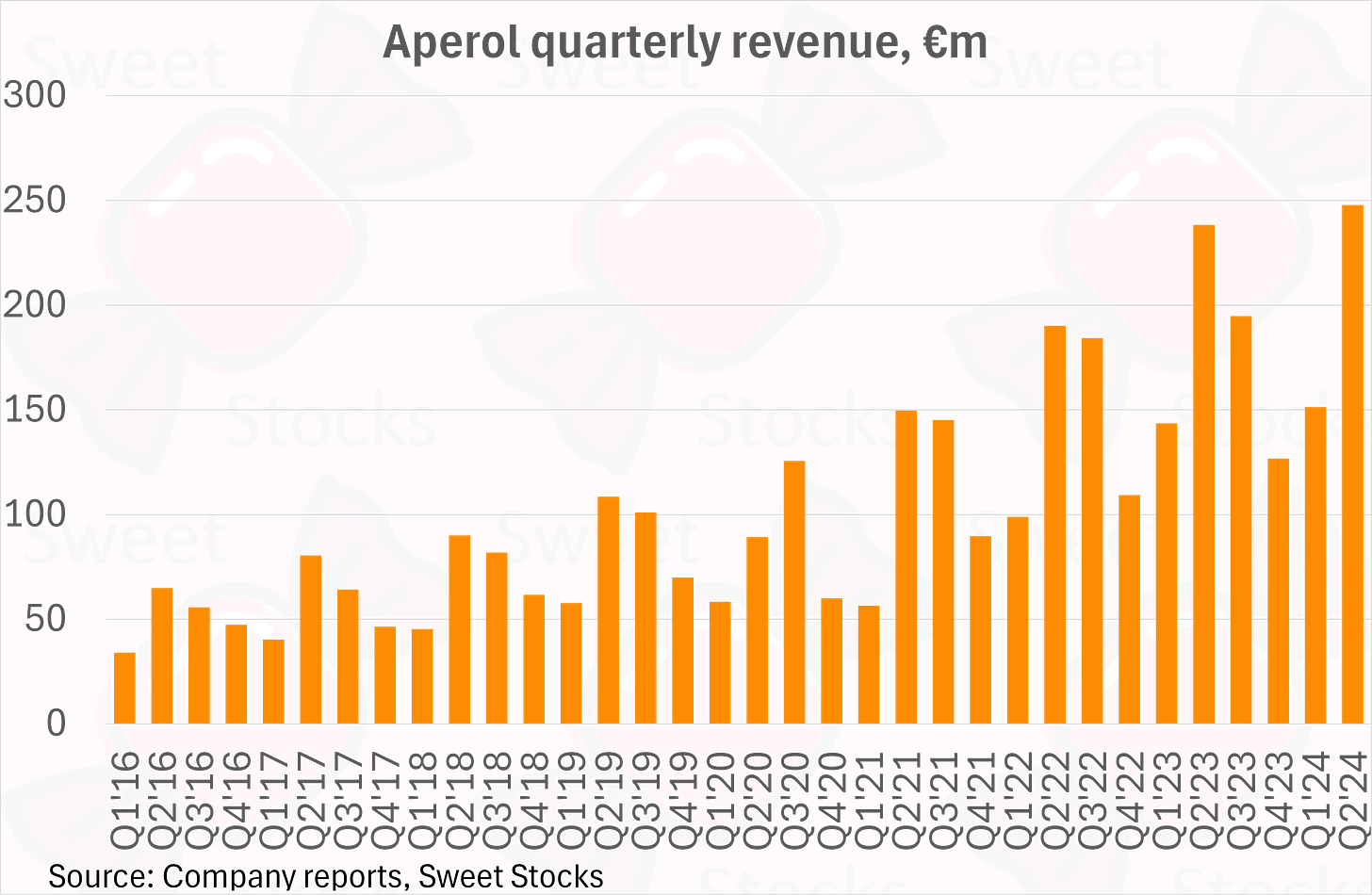

Aperol has delivered a 19% CAGR since it was acquired in 2003, reaching 24% of group sales. But it slowed to just +4.7% in H1, blaming bad weather and tough comps.

I argue that an investment in Campari today depends on Aperol being able to sustain double-digit growth for many years to come. Can it shrug off competitive attacks and the perceived risk of faddishness? I explore Aperol’s prospects in detail below.

If Aperol has legs, then now should be a great time to buy the stock. Espolòn tequila and the Campari brand itself have strong momentum. The Courvoisier acquisition sets up a long-dated next potential leg of growth. Noise around a rumoured investigation by the Italian authorities into Garavoglia’s tax affairs should not impact minority investors.

The stock is off 40% from its 2021 peak, and has de-rated heavily along with spirits peers. The sector is suffering a cyclical slowdown after the big post-Covid years. Speculative fears of a structural threat to alcohol consumption by young people represent a buying opportunity, in my view.

I have started a position in Campari at around the current price.

Background and management

Campari’s glorious history, dating back to 1860, is covered in my annex. Yet the modern group can be regarded as a start-up that was founded in 1994 by Luca Garavoglia. From 1998 to 2023 he grew revenue ninefold, from €334m to €2.9bn. See my chart below.

Garavoglia remains in place as chairman and controlling shareholder today. More ambitious than ever, he wants to catapult Campari up the ranks from global #6 spirits player into the top four, which would require a mammoth acquisition.

In 2020 Campari moved its domicile to the Netherlands. This enabled the introduction of multiple voting rights for long-term shareholders. This mechanism will allow Garavoglia to issue equity to fund a large acquisition, diluting his capital ownership while he retains majority voting control.

A generational management change just took place. The former CEO Bob Kunze-Concewitz retired in April 2024 after 17 years at the helm. He joined Campari in 2005 as Group Marketing Officer from Procter & Gamble.

His successor as CEO, Matteo Fantacchiotti, is new to the group since 2020. He joined as Managing Director for Asia. He came from Carlsberg where he served as Commercial Vice President for Asia, based in Hong Kong. His prior background includes Diageo and Nestle. His Asian experience is hoped to strengthen Aperol and Courvoisier in the region, which is currently tiny at just 4% of group sales excluding Australia.

The CFO, Paolo Marchesini, is even longer serving than Kunze-Concewitz. He joined Campari in 1997 and became CFO in 2000, leading the IPO the next year. In 2022 his role was extended to Chief Financial and Operating Officer. He has been locked in with a €30m ‘Last Mile’ golden handcuffs scheme until 2031.

The culture of the business is described by former insiders as extremely Italian. Perhaps not surprising, but what they mean is that the Campari way of doing business is insisted on throughout the global operations. This creates a strong and unified organisation, rather than a disparate group of businesses.

Aperol

Campari acquired Aperol in December 2003 for €147m. It came as part of Barbero, an Italian business that was owned by the Irish Cantrell & Cochrane, then controlled by BC Partners. (C&C today is listed in London as a UK and Ireland focused cider and beer concern with a $780m market cap. Its performance has been poor, as it has been unable to overcome tough category-geography fundamentals.)

Barbero delivered €63m of revenue for Campari in 2004, the first full year of ownership. Aperol brand revenue was just €27m.

Despite this tiny sales figure, Aperol was already well established in Italy. It was invented in 1919 as a straight liqueur. The Aperol Spritz cocktail followed in the 1950s. It was promoted effectively, as shown by the twentieth century assets below. (This article is recommended for a full rundown, including this 1980s TV commercial.)

Aperol had already been growing strongly prior to acquisition. Campari noted in their 2003 annual report that “Thanks to its distinctive qualities and an extremely successful marketing and promotions strategy, Aperol saw its sales rise by an impressive 16.5% per year on average in 2001-2003.”

Under Campari’s ownership, Aperol growth was accelerated and sustained for the next twenty years, as my chart below shows. The 19% CAGR is truly remarkable.

Both volume and price have contributed to the growth. My chart below shows volume has been the most significant driver, reaching nearly ten million nine-litre cases per year. The average revenue per litre achieved by Campari has risen from around €6 to over €8 in the last decade, thanks to deliberate price repositioning and a mix effect from the US, where Aperol is priced higher than in Europe.

(The €8 revenue per litre average excludes taxes and retailer margins, meaning that the average cost per bottle to the consumer is much higher.)

Internationalisation was a key factor. In 2005, 92% of Aperol sales were in Italy, with Germany the only other market of note. By 2011, Italy accounted for less than 50% of Aperol sales, while still growing double-digit each year in its own right. Switzerland, Austria and then France followed, as Campari honed its playbook to launch Aperol in successive new markets.

In 2023, the top five Aperol markets were Italy, Germany, US, France and UK. These countries accounted for 70% of total sales, as per the chart below.

Serious further upside could come from the US, where per capita consumption is far lower than in other current markets. Campari initially promoted Aperol in a limited number of coastal cities. The potential clearly exists to bring it to the rest of the country over time.

(However, a former senior Campari America executive has suggested in interesting transcripts on Third Bridge and Tegus that the bitter flavour profile and high price could hold it back. Aperol is sold at a higher price point in the US, making the Aperol Spritz a premium cocktail rather than an affordable drink as in Europe.)

The rest of the world also has plenty of room for further growth. Countries as diverse as Poland, Mexico, New Zealand, China and India all grew very strongly in 2023.

The Aperol playbook

Campari prides itself on a patient and long-term approach to brand development. For Aperol, the entire focus is on just one cocktail, the Aperol Spritz. It’s a summertime drink for the early-evening aperitif occasion that looks and tastes great.

Campari’s focus in each new market is on-premise activation, providing samples and getting liquid to lips. They show people how to make the cocktail correctly. (3 parts prosecco, 2 parts Aperol, 1 part soda water, over ice.)

Campari is strong on combining activation events and sponsorships with social media campaigns and influencers. For example, Aperol’s sponsorship of the Australian Open and US Open tennis tournaments revolves around huge bars serving the cocktail to influencers who are invited along to watch the tennis and post photos with their drinks.

Music festivals are of similar importance, with Coachella in California and Primavera in Barcelona the biggest Aperol sponsorships, both at the start of the summer seasons.

Stage two is to de-seasonalise the drink, including with apres-ski and events in months other than summer. (Stage three would be food pairing – this has only been achieved in Italy as yet.)

The Aperol franchise is currently still highly seasonal. My quarterly revenue chart shows Q2 and Q3 each year are most significant.

On average, the two peak quarters make up 63% of annual sales, as shown below.

Apart from looking and tasting fabulous, Aperol has some unique strengths that might not be obvious, and which have helped drive its success.

· Aperol’s very low alcohol by volume of just 11% is unique for any kind of spirit. This makes the drink light, refreshing and sessionable. Drinkers are recruited from beer as often as from other cocktails.

· The low alcohol content also directly leads to a very high gross margin for Campari. This is because in most countries lower ABV liquids attract much lower excise duties, while consumers still expect a selling price in line with the spirits category.

· The Aperol Spritz is demanded by name, which puts up a huge barrier to me-too competitors in the on-trade. By contrast, the Hugo Spritz is a generic term for an elderflower-based spritz, which gives Bacardi’s St-Germain brand a headache.

Heineken’s Chairman and CEO, Dolf van den Brink, generously expressed his admiration for Aperol during a Sep’23 presentation in the following Q&A exchange.

Q. Is there any one brand that's outside of your portfolio that you particularly admire? And that's not meant to be an M&A question, just to be very clear about that. But anything in wine, beer or spirits that you think is particularly impressive?

A. There's one thing that has been annoying me mightily, and that is Aperol Spritz. And my own 21-year-old daughter is drinking it. And you have to admire these guys. And as by origin a marketer, how they did that in the orange and the ritual, the glass, the aperitif occasion, I admire them. And they're a fierce competitor for that occasion, including in my own family, which is a bit sad.

Aperol competitors

For well over a decade, Aperol has faced hordes of competitors of all kinds. To date it has seen them all off.

· Cheater brands or me-too versions of Aperol can be found mainly in the off-trade. Lidl’s Bitterol and Aldi’s Aperini are two well-known versions. These have been available since at least 2017 in the UK, and far earlier in Germany.

· Rival spritz cocktails. Aperol’s popularity has created space for multiple different spritz cocktails to be offered, sometimes on a dedicated spritz menu. Popular versions include the Hugo Spritz (elderflower) and the Campari Spritz, while new entrants include Allora Limone Spritz. Campari itself can play this game, with its Sarti Rosa innovation for a sweeter flavoured spritz, and its Cynar Spritz for a darker vibe.

A bartender commented on Reddit earlier this year that

“I started bartending in 2011 and Aperol spritz was already a thing. Then there was a Hugo season 2012ish, then Lillet blanc + Schweppes russian wildberry 2014ish, then limoncello spritz 2017ish. In between negronis were the hot shit. This season it’s Sarti Spritz and I like it very much – but these are all seasonal drinks, the classic Aperol spritz is still on the throne after all these years.” [Source: Reddit.com/r/bartenders ]

· Rival premium aperitifs are an indirect kind of competition. Aperol has grown the aperitif occasion to such an extent that drinks such as Pernod Ricard’s Ramazzotti and Lillet are growing alongside Aperol.

Could Aperol be a fad?

A hard-to-disprove bear case is that Aperol Spritz is a fad, experiencing its moment in the sun but set to stop growing or even start shrinking.

It’s a valid concern. Spirit trends have certainly come and gone in the past. Ready-to-drink alcopops such as Smirnoff Ice and Bacardi Breezer came and went from the 1990s to the 2000s. (Smirnoff Ice came to a hard end when frat boys starting “icing” each other.)

More recently, a gin craze peaked around 2019. This is visible in Diageo’s sales by category: their Tanqueray, Gordon’s and Aviation gin portfolio outperformed the rest of their business hugely in FY18 and FY19, and has gone into freefall recently.

The key factors associated with the end of drinks trends are probably over-exposure and ceasing to be aspirational. On these counts, Aperol looks safe, in my view.

Over-exposure? Aperol revenue is still below a billion dollars, making it less than a blockbuster franchise on a global scale. Consumption per capita is extremely low in most countries, as shown in the table below. In the US and the UK in particular, many adults have not yet even heard of the drink.

Aspirational? To date, Campari has successfully positioned Aperol as a drink associated with the aperitif occasion, sunshine and friends. The fact that their brand is synonymous with the category gives them a high degree of control in questions such as how to extend the brand.

In conclusion, I expect Aperol to continue to grow by high single digits to low double digits throughout my three to five year investment horizon.

Campari brand

The Aperol acquisition was highly complementary to Campari’s original namesake brand. Both are bitter-tinged aperitifs to be mixed in popular, proprietary cocktails. There is obvious synergy in marketing and distributing them together.

The negroni was the focus for the Campari brand for much of the last twenty years. A real negroni can only be made with Campari, along with gin and vermouth.

More recently, the Campari Spritz has developed as a consumer-driven thing. It has enjoyed a halo effect from the Aperol Spritz. This partly explains the post-2021 acceleration in Campari sales, as shown in my chart below.

Campari has also deliberately taken price in the last few years, to elevate its namesake brand from its previous low price per litre, as shown below.

Espolòn tequila

Espolòn is Campari’s key tequila brand. They were early to the tequila category, thanks to having previously represented Cuervo’s 1800 and Gran Centenario brands in the US within their Skyy business on an agency basis. When Cuervo terminated that arrangement in 2007, Campari bought Cabo Wabo and Espolòn to have its own brands. Cabo Wabo was positioned as an ultra premium tequila, and never really took off.

Espolòn, on the other hand, has been wildly successful. Campari revamped the brand positioning and changed the packaging post acquisition. It is now regarded as a great value, $25 tequila with a cool image, and very popular with bartenders for making cocktails such as palomas and margaritas. My chart below shows the meteoric revenue growth.

Campari would like to reposition Espolòn as a premium tequila, and has been increasing prices steadily, as shown in my volume and price chart below. However, there is likely a limit to how much price they can take while retaining their core market of bartenders using it to mix drinks.

Despite the huge marketing and sales success, Espolòn has been highly dilutive to profitability for Campari at group level up until now. This is due to the spike in agave prices, and the brand’s positioning as a 100% agave liquid. The gross margin has been as low as 35-40%.

Campari has taken actions to secure more agave, including its own planting arrangements and long-term contracts alongside spot purchases. Eventually the agave price should normalise down, at which point Espolòn could become a second profit driver for the group alongside the aperitifs.

Other brands

The three brands discussed above contribute 44% of total sales, and a higher proportion of growth and profits, given the high gross margins of the aperitifs.

Campari’s portfolio also includes Wild Turkey bourbons, Jamaican rums, SKYY vodka, Grand Marnier, and now also Courvoisier, as well as many regional and local brands and development projects. In the interest of brevity, I won’t dwell on these here, because I don’t expect them to move the stock within my investment horizon. Suffice to say that all except SKYY are in good health, and have niche positioning and/or paths to development and growth within their categories. SKYY is important within the portfolio mainly for the volume it brings to the US three-tier distribution system, boosting Campari’s relationship with their distributor Southern Glazer’s.

Courvoisier is an ambitious play to move into cognac. Despite the great historic name, under Beam-Suntory’s ownership it was a weak #4 player that competed on price. Expectations are low in the near term, both for the brand and the category, which has been decimated due to the collapse of luxury consumption, especially in Asia. Campari management will work to reposition the brand for longer term success.

Why has the stock been so weak?

The stock is off 40% from its 2021 peak, and has de-rated from >40x P/E to 23x – see chart below. Other spirits stocks have also de-rated over the same period: this is mainly a whole category story rather than Campari-specific weakness.

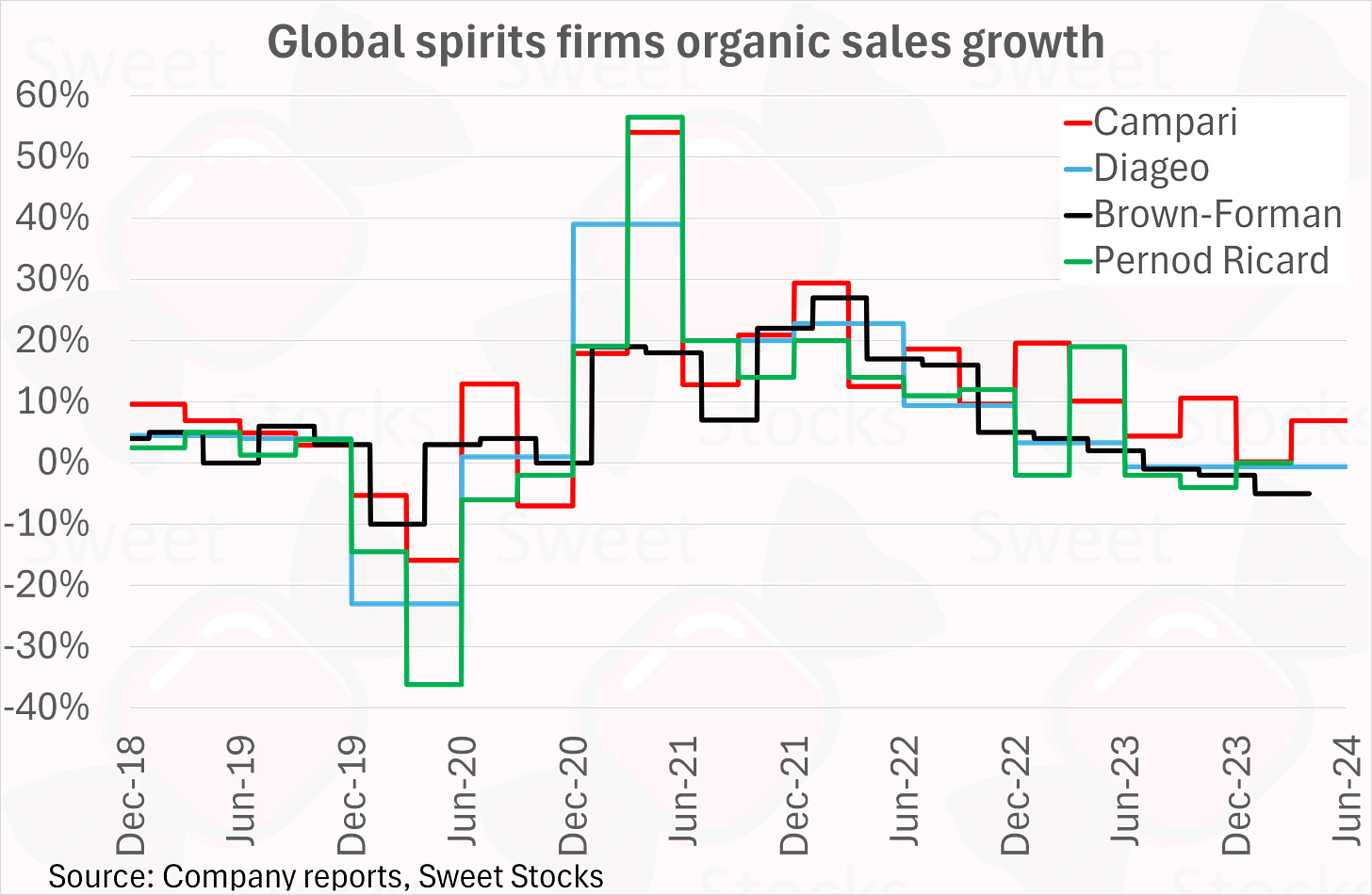

As my chart below shows, global spirits sales boomed in 2021 and 2022. Consumers had the money and inclination to splash out on premium spirits in particular. Inflationary price hikes also flattered the organic growth rates.

More recently, the chart shows a clear slowdown. Three of Campari’s biggest peers have zero or negative organic growth rates for the latest reported periods. Campari has thus far held up better by comparison, probably helped by its limited exposure to the most troubled luxury and super-premium segments.

While Campari has fared well on sales, it has disappointed on profits. Consensus now expects EPS of €0.33 for 2024E, a sharp 25% cut from the €0.44 that was expected just over a year ago.

As well as prolonged agave cost squeeze, a recent cause of the downgrades is dilution from the $1.2bn of Courvoisier equity and convertible bonds. (The cognac business is in such poor initial shape that it is guided to make nil profit contribution in 2024E, despite eight months of ownership.)

Separately, Milan’s Public Prosecutor is investigating Garavoglia’s holding company, Lagfin, for an alleged €1.2bn tax evasion carried out when the company headquarters were moved to Holland, according to the Italian press. The listco has confirmed that “Neither Davide Campari-Milano NV nor any of its subsidiaries are being investigated by the authorities”. The Agnelli-Elkann family's Exor previously underwent a similar transaction and received a similar investigation. I do not see this investigation as posing a threat to minority shareholders.

Finally, there is a theory doing the rounds that the current weakness in spirit sales relates in some way to the supposed lower propensity of Gen Z to drink alcohol. In my view, this is unevidenced and speculative. It is extremely difficult to find high quality, valid data on changes in drinking habits over time (as opposed to unreliable clickbait survey data). Moreover, drinking habits vary significantly by country. Most of all, any changes in propensity to drink would feed through extremely gradually.

For example, the first chart below suggests a modest reduction in participation by men over the last decade in England. This was compiled by the House of Commons Library from health survey data.

However, the second chart, below, shows UK data on total alcohol consumption from HMRC, based on excise receipts and its estimate of the tax gap for smuggled alcohol. The well-understood relative decline of beer is evident, but the spirits volumes have shown a rising trend, in line with improved affordability over time.

Financials and estimates

Campari’s gross margins are lower than its bigger spirits peers, but not dramatically so. My chart below shows that all three peers are now clustered at 60%, with Campari on 58%. This is impressive given Campari’s smaller scale and relative lack of luxury and ultra-premium brands.

Campari’s GPM decline since 2019 is principally due to the agave price spike, combined with Espolòn’s breakneck growth in the same period.

The business model in spirits is to reinvest steadily in A&P to protect and build your brands. Campari follows this principle with a steady 17-18% A&P to sales ratio, as shown in my chart. However, Campari’s mix is distinctively different, with a focus on activations and online / social media rather than traditional television and print media.

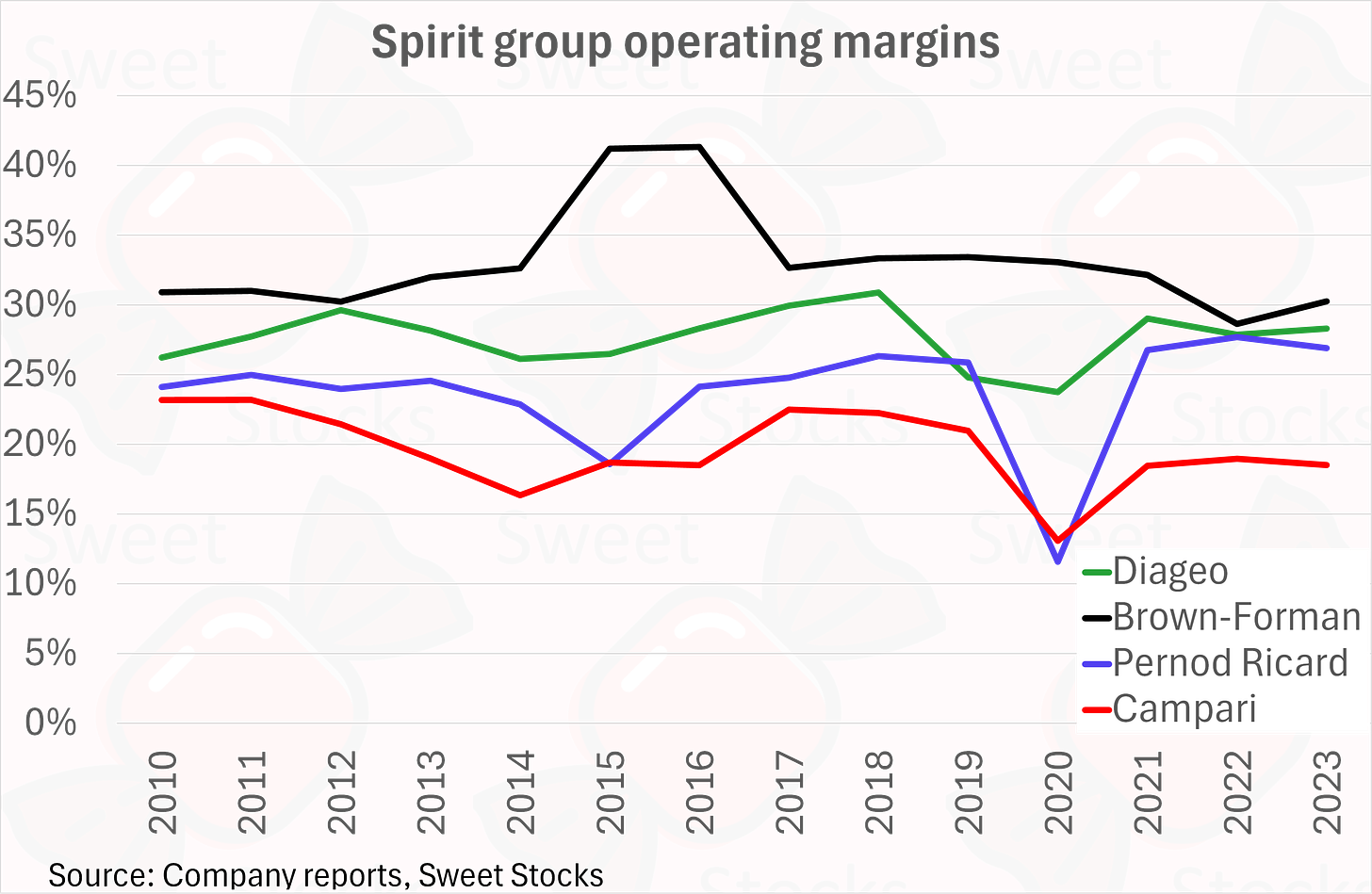

When it comes to operating margin, Campari lags behind its larger peers. This likely reflects lack of scale, as well as the specific agave issue in recent years. Couvoisier will likely provide further downward pressure on margin in the next couple of years, as it provides some revenue with very little profit initially.

Free cash flow has been fairly steady until 2023. That year saw a record €296m of capital expenditure, as well as a large working capital build that was partly related. The company is in the middle of large capacity expansion projects in Italy, Kentucky and Mexico. It is investing a total of €550m of extraordinary capex in FY23-FY25 inclusive. This will double capacity in aperitifs, bourbon and tequila.

Net debt has jumped to a peak level of €2.55bn, equivalent to 3.5x EBITDA, at June 2024. This is due to the exceptional capex programme described above, as well as the acquisition of Courvoisier. My chart below shows Campari’s preferred target range of 2x to 3x for leverage. They should return to this zone within the next year or so, helped especially by working capital normalisation.

My estimates for Campari are shown below. I am a touch behind consensus. The set-up for 2025E in particular should be favourable, as the various margin headwinds (agave, glass and using up old stock) recede.

As stated above, I consider Campari to be attractive at the current valuation, and have recently started a position.

Annex: history of Campari

1860 is the usual start date for the history of Campari, when Gaspare Campari opened a café near Milan, then moving to the city itself in 1862. He invented the distinctive and revolutionary bitter red liqueur with a secret recipe. He died in 1882 aged just 54, leaving his wife Letizia Galli to run the business while raising their five children. In 1886 she exhibited the business abroad for the first time, at an Expo in Barcelona, marking the start of Campari’s export strategy. Eventually their son Davide came of age and took on the business. He added new drinks to the roster, and made groundbreaking use of advertising to expand sales enormously.

In 1932, with no children of his own, Davide passed the business to his nephew Antonio Migliavacca.

In 1954, however, Antonio Migliavacca died, also without heirs. The reins of the business passed to his wife Angiola Maria Migliavacca, a tenacious woman who had been a teacher all her life without any entrepreneurial or managerial experience, and who was 61 years old at the time. However, being a woman of strong character, great intelligence, great common sense and with an extraordinary capacity for work, she managed to lead the company for the next twenty years, consolidating the results, expanding the turnover and above all exports, always focusing on the technological renewal of the plants. Mrs. Angiola retired from the business in 1976, when the baton passed to Domenico Garavoglia, a Campari manager who had been, among other things, her student when she was a teacher and who over the years had accumulated a great deal of experience and demonstrated undoubted managerial skills. [Source]

In 1982, when Angiola Maria died, Domenico formally inherited the company as a reward for his loyalty. He died in 1992, leaving the business to his wife, Rosa Anna Magno Garavoglia. She appointed Luca Garavoglia as chairman and CEO in 1994, aged 25. The rest is history.

Exceptional writedown as always