Cowick Hall in rural East Yorkshire is a beautiful 17th-century mansion. Since 1955 it has served as the head office for Croda International, the $9bn provider of beauty, consumer and life sciences ingredients.

The building makes a quirky headquarters for a global chemicals firm. But Croda is an unusual business. Its culture of innovation has persisted through decades of dizzying acquisitions and disposals. It provides its customers with high-value solutions, and charges prices to match.

This distinctive culture has produced super-high margins that set it apart from its chemicals peers, including an operating profit margin that averaged 24% for twelve years from 2011.

In 2023 that run came to a crashing end, as the margin fell to 19%. For 2024, Croda has guided to a 16% margin that is nowhere near what its shareholders expect.

In this write-up I introduce Croda’s business, and cover thirty years of Croda’s history and deals – not as an academic exercise, but because it is crucial to understand how the sky-high margins of the 2010s were achieved.

Only then can we get to grips with the grisly profit warnings, and take a view on the million dollar question asked by the Berenberg analyst: “What do you view as an achievable long-term operating margin for the business?”

My conclusion is that Croda will probably be fine. I’m an optimist by nature, and I run a reasonably diversified portfolio. As such I have accumulated a position since the warnings began.

In my base case, management have finally reset estimates to a suitably conservative level with last month’s third warning. Confidence will be rebuilt by quarterly reporting with no nasty surprises. Operating leverage works both ways: the margin plunge can turn into a rapid rebound when volumes return within the next couple of years. Life Sciences has impressive growth potential in biologics and nucleic acid therapies. The group margin makes a full recovery to 25% by 2027. A 25% EPS CAGR from 2024-27 drives c.50% upside for the stock over three years while also allowing it to de-rate to a rational level.

However, I can’t entirely rule out a catastrophic downside scenario. In this version, a further nasty profit warning would destroy the CEO’s credibility. It would turn out that Croda’s profitability and growth are permanently impaired due to having flown too close to the sun with its aggressive approach to pricing. The stock would de-rate sharply on lower estimates, giving a further 30-40% downside. I’ll be monitoring vigilantly for any signs of the above.

The write-up is structured as follows.

· Overview of Croda and its track record.

· History of Croda’s leadership

· Review of the key acquisitions since the 1990s that made Croda what it is today

· Specific warning signs that Croda may have pushed price hikes too far

· The profit warnings of 2023-24

· My estimates

As always, feedback is very welcome.

Overview of Croda

Croda is a specialty chemicals firm with an unusually rich mix of high-value, low-volume niche products. The business today is split into three market segments and eight business areas, as shown in my chart below. The broad mix is 52% Consumer Care, 36% Life Sciences and 12% Industrial which is a residual category.

In reality, even the eight business areas can be further sub-divided into many individual niche businesses, based on Croda’s concept of thousands of products to thousands of customers.

Unifying most of Croda’s businesses are shared underlying chemistry platforms and shared production facilities. Some brief details will be helpful.

· Croda is built on oleochemicals, derived from vegetable and animal sources rather than petrochemicals. This is favourable for environmental sustainability.

· Key product families include lanolins (derived from woolgrease, secreted by the sebaceous glands in sheepskin), fatty acids, surfactants, emollients, emulsifiers, adjuvants and excipients.

· 59% of Croda’s organic raw materials are bio-based, including rapeseed oil, fish oil, palm oil, woolgrease and ethylene oxide made with bio-ethanol.

· 41% of raw materials are still derived from petrochemical feedstocks. Croda is investing significant capex to reach its target of 75% bio-based by 2030.

Croda is well spread globally, with a 2023 sales split of 41% EMEA, 23% North America, 11% Latin America and 25% Asia.

Track record

My chart below shows 45 years of sales and margin history. Croda’s consistent preference for profit over volume is clearly visible, with sales often flatlining aside from major acquisitions, but the profit margin climbing ever higher from the 5% starting level to the c.25% plateau achieved in the 2010s.

Despite its large appetite for M&A, Croda has been stingy in issuing equity over the years, preferring to fund purchases from disposals and free cash flow. The share count in 2023 was only 6% higher than in 2000. Therefore earnings per share had grown impressively prior to 2023 – see chart below.

Prior to 2023, Croda had a track record of double-digit ROIC, using a rigorous definition that adds back any impaired goodwill and accumulated amortisation of acquired intangibles to the denominator. From a peak in 2011-13, ROIC fell due to high capex and technology-focused acquisitions with long-dated pay-offs. See chart below.

Below is the track record of capex and depreciation. Overall, I commend Croda’s commitment to investing in their business to support growth and innovation. Recent capex has focused on Life Sciences expansion. (From 2015-17 they invested $170m in a bio-based ethylene oxide project at their Atlas Point plant in Delaware, which they botched with a leak, a big delay, lawsuits, fines etc. Not their finest hour.)

History – management

Croda’s unique culture has come from great continuity of leadership, with just four CEOs in 74 years.

Sir Freddie Wood was the architect of the modern Croda. From 1950 to 1986 he grew it from a tiny family business to a listed global player with a fierce preference for profit over sales growth.

“In 1950, newly appointed Sales Director Fred Wood took Croda’s products to North America by establishing a sales office in New York. Returning to the UK as Managing Director just three years later, Wood left behind a growing customer base, with many leading cosmetic companies both there and in Europe starting to incorporate Croda products into their formulations.” [Source]

Wood retired in 1986. Keith Hopkins took over as CEO from 1987, and then as non-exec Chairman from 1999, having joined Croda from Unilever back in 1976. Hopkins transformed Croda from a diversified 1980s conglomerate to a focused speciality chemicals firm.

“In the eighties the Group owned a wide variety of manufacturing businesses in chemicals, coatings, adhesives, inks and soap as well as several trading companies.

“As many markets were moving away from petrochemical products to naturally derived ingredients the outlook for oleochemicals was very good. A strategy was, therefore, developed to expand this business worldwide where we could see sustainable profitable growth.

“We disposed of a string of businesses which did not fit such as edible oils, pet foods, inks, graphic supplies, honey and nut trading, and rendering. Our disposal of major businesses as well as many minor ones, raised substantial funds for reinvestment in new plant.

“We have greatly improved the quality of our management through better recruitment and training and importantly by instigating and maintaining the recruitment of between ten and twenty graduates annually, directly from universities into all sections of the business.

“It is impossible to speak too highly of the energy, dedication and single minded determination with which Keith Hopkins has carried out his duties as Chief Executive over the last twelve years.”

(Source: 1997 Annual Report.)

Mike Humphrey became CEO from 1999 until 2011, having joined Croda in 1969 as a management trainee. His brilliant stint at the helm was capped by the transformational reverse takeover and integration of Uniqema in 2006, a business that was twice Croda’s size by sales at the time. See full discussion below in the section on key acquisitions.

Steve Foots took over as CEO in 2012, having joined Croda in 1990 as a graduate trainee. He remains CEO to this day (age 55). There is as yet no pressure on him to step down, despite the collapse in earnings and share price. We’ll need to wait a few more years before we can judge his success.

History – key M&A

This section is lengthy, but in my view is key to understanding how today’s Croda came into existence. The TLDR is that Croda has a strong track record in executing and integrating key deals of varying types. Their M&A capability is a key strength, in my view.

In 1991 Croda acquired Novarom, a German plant extracts business (since renamed Crodarom). In 1997 they bought Sederma, a French maker of anti-ageing peptides for luxury skin care. These two businesses, acquired as tiddlers, have grown under Croda’s stewardship to become the c.£130m Beauty Actives business at nosebleed margins. Sederma in particular is a crown jewel asset of the group, with consistent superior growth and top margins, based on its undisputed global skin care science and innnovation leadership.

In 2006 Croda bought Uniqema from ICI for £410m. This was a pivotal deal. Uniqema was twice Croda’s size in terms of trailing sales (£626m vs £306m), but smaller in terms of profit with an EBITDA margin of just 8% compared to Croda’s 21%.

Croda had coveted the business since 1999, and made a previous bid in 2004 which was rejected. By 2006 ICI was a distressed seller and needed to deleverage, so it accepted Croda’s bid.

What Croda bought was mainly the former Unilever chemicals business that ICI had acquired in 1997, plus ICI’s own Surfactants speciality business. (Givaudan bought the Quest fragrances and flavours business from ICI at around the same time, also ex Unilever, which was equally transformational for them.)

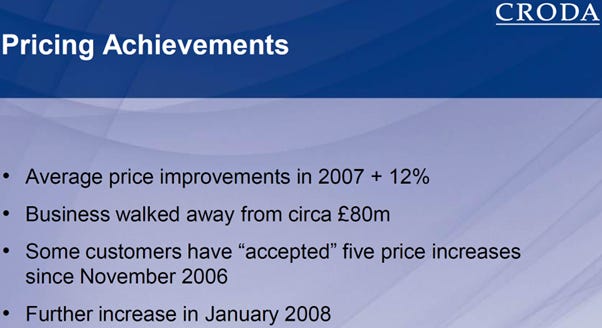

Croda took decisive restructuring actions upfront. They terminated leases and distribution arrangements. They rapidly integrated the good bits of Uniqema into Croda, cutting 290 jobs including 8 of 11 Uniqema’s senior management. They raised £124m from prompt disposals of unwanted Uniqema businesses in 2007 and 2008. And crucially, they demarketed the remaining low-margin commodity business by the simple expedient of multiple rapid price hikes. They were extremely frank in their thesis that Uniqema had been guilty of badly underpricing its products – see quotes and the 2007 slide below.

“We have a strong belief that Uniqema’s high quality products have been underpriced and steps have already been taken to increase selling prices”. (2006 Annual Report)

“We have significantly improved the margins of the acquired business. This was achieved by a combination of focus on value and moving away from the flawed Uniqema distribution model which gave more margin to the intermediary than to the producer.” (2007 Annual Report)

By 2011, with Uniqema’s scale at Croda’s margins, the combined group managed £238m of operating profit, up 4.5x from the 2005 Croda standalone level. Uniqema must rank as one of the great European acquisitions of this century.

In late 2015, Croda bought Incotec, a Netherlands leader in seed coating systems. They paid £109m for £50m trailing sales and a c.10% OP margin. In classic Croda fashion, they invested in innovation and repositioned the business upmarket, shifting focus from field crop seeds towards treatments for higher-value vegetable seeds.

There is also a sustainability-linked growth driver. It turns out that common practice until now has been to use seed coatings that contain microplastics. The EU is banning this practice by 2028. Incotec has been first to market with new microplastic-free seed coatings, which drove strong growth in 2022 and 2023 even as Croda’s other businesses faltered.

Incotec today does approx £90m sales at 20% OPM, making it a highly successful bolt-on acquisition.

In July 2020 Croda miraculously bought Avanti Polar Lipids, based near Birmingham, Alabama. Avanti is the world leader in lipid nanoparticle (LNP) drug delivery systems that carry nucleic acid material. These are a critical component of Pfizer-BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccine. Croda paid a total of £174m for a business that immediately did $410m of high-margin COVID revenue in the three years from 2021-23. LNPs will in future have lots of uses beyond COVID. Avanti has a promising pipeline of a hundred future nucleic acid therapies: Croda say it is supporting >50% of clinical trials that specify a lipid delivery system.

(The COVID revenue has now finished. Its lumpiness was reasonably well understood by the market all along, and was not the cause of the series of profit warnings, which relate to destocking and operating deleverage in Croda’s core consumer and industrial markets.)

In late 2020 Croda bought Iberchem, a Spanish fragrances and flavours (F&F) business. They paid £736m for a business with £166m of trailing sales and a 22% EBITDA margin. The move was surprising for a couple of reasons.

· F&F is a distinct sector that is dominated by the Big 4 of Givaudan, Symrise, IFF and Firmenich (now merged with DSM).

· Operating margins in F&F have been far lower than Croda’s 24-25% level. My chart below shows the Big 4 F&F firms had operating margins 870bp lower than Croda’s in the years prior to 2023, when Croda’s dramatic collapse caused a partial convergence. Was Croda not worried about margin dilution from a F&F business?

However, there was a sound acquisition logic. Iberchem mainly sells fragrances for perfumes, personal care products and laundry care. It specialises in serving local and regional customers in emerging markets. Customer overlap with Croda’s beauty and home care customers is surprisingly low. Therefore Croda can open a lot of doors for Iberchem to accelerate its growth. In 2021, Croda bolted on a fine fragrance acquisition, Parfex based in Grasse, for £35m, to access premium personal care and fine perfumery markets.

(The Flavours business, c.20% of the total, has no such logic. Croda plans to dispose of this business in the medium term.)

The Iberchem acquisition has proved to be a success to date. After a sluggish 2021, Iberchem grew by 20% in 2022 and by 18% in 2023, the star in an otherwise awful year. Its agile and cost-competitive model is allowing it to win business in the Middle East and other regions, growing faster than the Big 4 who are tied to the multinationals.

In July 2023 Croda bought Solus Biotech, a Korean leader in premium biotech-derived beauty actives. Solus provides ceramides, phospholipids and natural retinol. Croda has high expectations for Solus to contribute to both Sederma and the Life Sciences business. Croda paid £227m for a business that did just £28m of sales in 2022 with 95 employees. The price sounds high, but Croda’s strong track record of success in key acquisitions earns them the benefit of the doubt, in my view.

(The vendor was Solus Advanced Materials, 336370.KS, a $757m electronic materials business that came out of Doosan via domestic PE. According to the Korean press, other auction participants were ADM, Solvay and Evonik. L’Oreal is mentioned as the flagship customer.)

Disposal of Performance Technologies and Industrial Chemicals package to Cargill

In December 2021 Croda announced the disposal of a package of operations to Cargill for a headline enterprise value of €915m / £778m. This seemed like a dream deal, raising a lot of cash from the ugly sister industrial businesses to increase the concentration on Consumer and Life Sciences.

The deal was completed in July 2022, at a revised headline value of €775m / £665m. The lower value reflected Croda’s inability to include a 65%-owned Chinese business in the sale, due to lack of agreement by the minority partner. Ultimate net cash proceeds were £574m after chunky separation costs.

Today, the deal looks a dud. The underlying problem is the high degree of interdependency with the “good” parts of Croda. Shared manufacturing plants produce industrial products alongside high-value consumer and life sciences products, thereby enhancing asset utilisation and cost absorption.

My interpretation is that to get the deal over the line, Croda allowed Cargill to pick and choose the pieces they wanted (just four plants, plus lab facilities and sales operations). Croda retained a number of plants, and signed long-term supply agreements to sell Cargill certain ingredients from those retained plants.

The evidence from 2023 is that this arrangement is working poorly for Croda. Cargill was free to slash volumes purchased from Croda by c.35%, given weak end demand. Yet Croda is presumably still obligated to maintain availability to Cargill, which may restrict its freedom to optimise its assets.

The extent to which Croda can restore volumes and profitability in the remaining Industrial business is one of the big uncertainties.

Evidence that Croda pushed price hikes too far

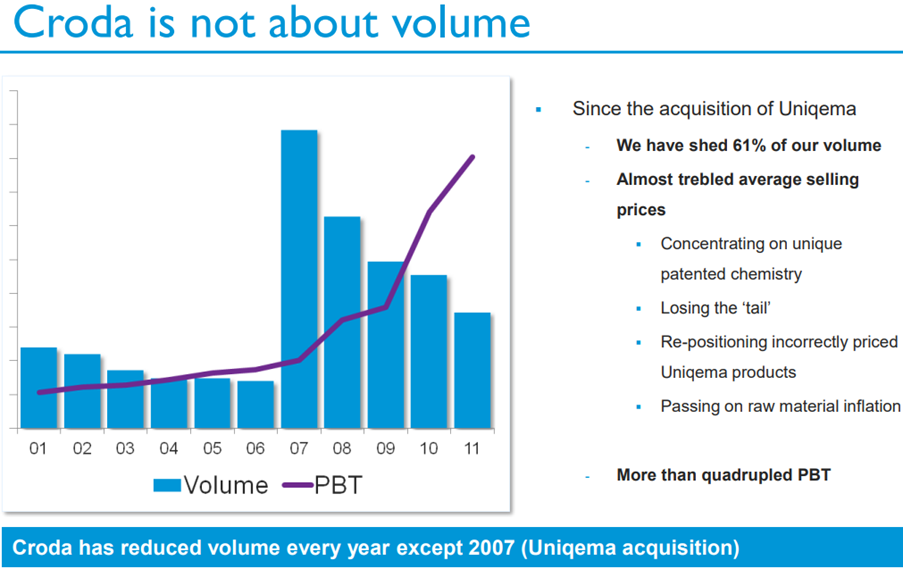

Croda has always expressed a preference for profit over volume. The slide below from the 2011 results presentation is remarkable: I am not aware of many successful companies that boast of shrinking volumes over a long period in this way.

Pride comes before a fall, and immediately after 2011 Croda entered a sustained run of disappointing low single digit organic sales growth. This was seen not only in the industrial segments that were supposed to shed volumes, but also in the core Consumer Care segment. My chart below illustrates this.

What caused the anaemic organic growth? Croda usually blamed the economy – see my table below. This is puzzling given that Croda’s focus on personal care and healthcare markets ought to be less cyclically exposed, as was the case in the 2008 financial crisis when Croda came through unscathed.

I suspect instead that the cumulative effect of years of aggressive pricing weighed on their growth. In the 2017 annual report, Croda made an interesting confession. They wrote:

“Sales to multinational customers also returned to growth, after several difficult years”.

This was a surprise, because Croda’s previous reports had not made any clear mention of a loss of sales from multinational customers. An expert call with a former Croda global marketing manager from September 2019 sheds some light.

“Q. Why is Croda losing so much market share to competitors in the multinational category?”

“A. Margin, because for commodities, Croda called it differentiated products, Croda increased price continuously in the past, starting from 2010, I think, then some companies like P&G decided to move away totally, 4-5 years ago. Some companies like L’Oréal, they brought in more secondary suppliers, which hit Croda’s margin a lot and pushed Croda to reduce their margin. They still kept the business, but in terms of the revenues it dropped a lot at this customer end. That’s the main reason. [Source: Third Bridge Forum, Sep 2019] “

My conclusion is that Croda does follow a strong pricing policy, and this does lead to ongoing price-volume trade-offs and skirmishes with customers at the less differentiated end of its portfolio.

However, Croda is innovative enough to come up with a lot of products with very high value-added that justify high prices. Over time, I expect Croda to be able to keep “running up the down escalator” thanks to new and protected product introductions that should support profitable growth.

Recent events are testing this confidence to the limit.

The profit warnings

This time last year, Croda was expected to earn £515m of EBIT in 2024. Since then, profit warnings in June, October and February have cut the 2024 consensus EBIT estimate to £297m, for a shocking 42% cumulative downgrade. The trend of analyst estimates is shown below.

Why the huge downgrade? The company’s explanation for what went wrong in 2023 is shown below, from the 2023 full year results presentation given a month ago.

Note that three of these bullet points should not have come as a surprise to management or the market. The tough comp from a record 2022 result, the divestment of PTIC (completed in July 2022) and the normalisation of Covid revenue (already discussed and correctly guided in the February 2023 conference call) were known facts. It seems the implications for profit forecasts were not properly understood by management or analysts, which is a separate matter.

The ”new” events most to blame for the warnings were

(1) unexpected sales falls across large parts of the core business, blamed on destocking and demand weakness (with organic sales -11% at group level in 2023); and

(2) a hit of 8pp to operating profit margin (from 2022 to 2024E) due to massive operating deleverage.

Beauty Care (-11%), Crop (-19%) and Industrial (-35%) were hardest hit by surprise sales plunges in 2023. Referring to Croda’s business mix in my chart below, these areas added up to 49% of total sales at the end of 2023. In addition, Beauty Actives (-1%) and Home Care (-1%) also had weaker than expected sales, as did consumer health ingredients, the least sexy business within Pharma. In total, around two-thirds of the group failed to perform in 2023.

Croda primarily blamed destocking cycles across the businesses, as follows.

In Consumer Care, destocking had already started in H2 of 2022. This partly drove a sharp 12% fall in volume in 2022, which was papered over by a 22% increase in price/mix. In the 2023 warnings, management said the destocking was longer and deeper than they expected. However, the chart below suggests the trough was early in 2023, with sequential improvement since then. The original 2023 guidance must have been based on an aggressive bounce-back forecast.

The other important driver of 2022’s volume falls in Consumer Care was an unfortunate episode of “selective demarketing of lower margin products due to capacity constraints in some Croda sites”. Croda took some plants in the US offline for catch-up maintenance, and disappointed customers who switched to other providers. In last month’s call the CFO updated that “we are having to give away some tactical price to get some of that volume back”.

(This ties in with a juicy Third Bridge comment from a US sales manager at Zschimmer & Schwarz in January 2024: “the word on the market is that Croda are being ultra-aggressive in industrial markets to try to regain market share any way possible with prices, because they do not have relationships with these customers anymore”.)

The Crop business saw “rapid” destocking start in Q2 of 2023. Croda supplies formulation aids and adjuvants to 4-5 pesticide multinationals, with higher customer concentration than in other businesses. Crop will be slowest to recover, with timing unknown.

The Industrial business virtually ground to a halt in the second half of 2023, with sales down 50% yoy and profit close to zero: see chart below. Visibility is especially low because in July 2022 Croda sold much (but not all) of what used to be Industrial and Performance Technologies to Cargill. See detailed discussion in the M&A section above. In short, the shape of any Industrial recovery is especially uncertain.

Can we trust management’s explanations around the profit warnings?

Croda is likely a good buy right now if we can take management at face value, which I do. The company has been victim of an essentially temporary and cyclical shock, and will claw back sales and margins in the coming years.

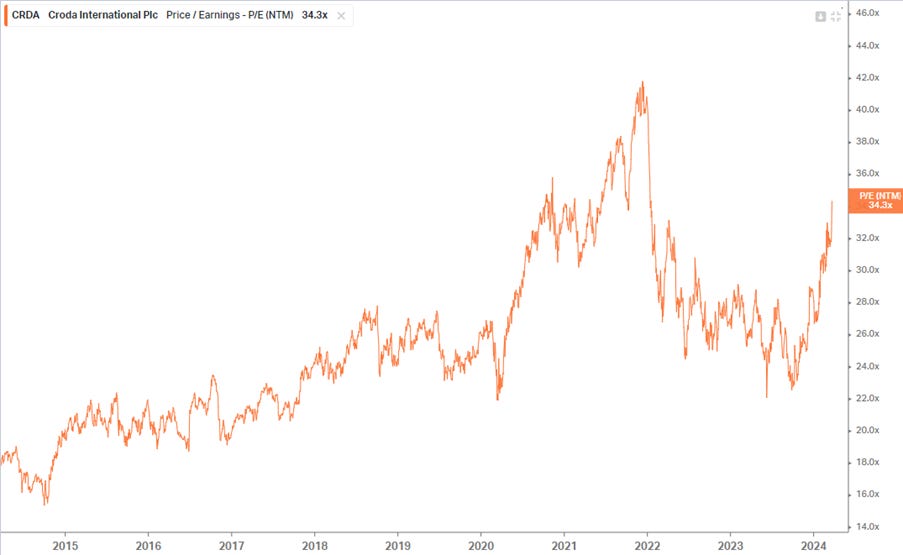

The stock trades at 35x trough earnings for the current year, and 19x peak earnings from 2022. Investors are willing to be patient because they expect the peak to be regained and surpassed in due course, justifying a high rating.

Sell-side analysts remain generally positive with Buy and Hold recommendations. At present there is only one disclosed short position above 0.5%.

All of the above suggests that most market participants are sanguine about Croda’s recovery. To state the obvious, the stock would have enormous further downside if it turns out that Croda’s problems are more structural than has yet been confessed. Any further warnings would put irresistible pressure on the CEO’s position. A painful re-assessment of Croda’s underlying quality could force a drastic de-rating. The unique culture of innovation could come to an end, causing a staff exodus and further uncertainty. In that situation Croda would become vulnerable to an opportunistic bidder, but only at a knock-down price.

Steve Foots is the CEO in question. He took over as CEO in 2012, having joined Croda in 1990 as a graduate trainee. He remains CEO to this day (age 55). As yet there is zero pressure on him to step down, despite the collapse in earnings and share price.

In my history section, I emphasise the unusual continuity of leadership at Croda. Every CEO since 1950 has been promoted from within after long service. They serve as guardians of Croda’s unique culture within the organisation. Hence we would be in uncharted waters for the company if Foots was forced to step down.

Louise Burdett, the CFO, is making a strangely short cameo appearance during the crisis. She only joined Croda at the start of 2023, when she succeeded Jez Maiden, who had served eight years as CFO. She presented the three profit warnings in June, October and February. In the midst of this, in December 2023 she informed the board that she was resigning to take over as CFO at Spirax-Sarco in June 2024. The search for her replacement continues, with an announcement due soon.

The credibility of Croda’s financial guidance is reduced by having what amounts to an interim CFO at the helm during this difficult period.

For completeness, I note that Dame Anita Frew, Chair since 2015, is retiring from the board in line with normal good practice after nine years. Her replacement, Danuta Gray, will take over in April. It’s not clear whether Chairs have played a major role at Croda, given the power of the long-serving CEOs and Executive Committee members.

Estimates

As stated at the top, my base case is for a recovery from the current slump that can be sharper than what the sell-side expects in 2025E and 2026E. Below are my forecasts, together with the segment detail. Life Sciences and Consumer Care should both return to form, in which case the exact recovery profile of Industrial will not be too important.

Speaking as a chemist and finance guy, I cannot praise this analysis enough. Not only informative and deep, but a thoroughly enjoyable read. I am not ready to buy yet but have been watching Croda for a couple of years. Previously, I just thought they were too expensive.

Another chemical company, operating in an interesting space, that you might like to look at, is Norwegian company, Borregaard, which I have owned for several years in my portfolio. They are listed on both Oslo and Stockholm and can be settled over a UK platform (SEDOL: B9134C0).

Thank you once again for sharing your insights.

Thanks for this. Great detail