WiseTech Global is Australia’s hottest vertical software stock. Its USD27bn market cap implies a rating of 30x sales, 60x EBITDA or 100x P/E on a next 12 month basis. A 33% revenue CAGR since IPO and a near-50% EBITDA margin underpin this.

As fundamentally attractive as WiseTech is, I struggle to pay those kinds of valuations.

Why is WiseTech so special? Its product, called CargoWise, gives its freight forwarder customers a competitive advantage over their peers using legacy or custom-built systems. And it looks to be establishing a de facto monopoly position as the only eligible solution.

Danish forwarder DSV is the poster child for this. A loyal customer since 2008, DSV has used its CargoWise-driven cost advantage to buy up less-efficient peers, switch them over to CargoWise, and raise their margins significantly.

I introduce the freight forwarding industry and profile DSV alongside two major peers. I show how DSV has used CargoWise to turbocharge its growth and margins, with more to come.

The cycle is still normalising after the 2021-22 freight rate spike, which drove windfall profits for carriers and forwarders alike. This has caused downgrades and uncertainty. Meanwhile, DSV is a finalist in the auction of DB Schenker, which at c.$15bn would be by far the biggest deal yet.

In this context, DSV trades at 1.8x sales or 20x P/E, much more palatable for me than WiseTech. Based on my research, I am tempted to start a position in DSV at close to the current level. I have not yet bought. Feedback is welcome.

What is a freight forwarder?

World trade depends on importing and exporting goods by container ship (lowest cost) or by air freight (fastest).

Companies with goods to move are called shippers. There are hundreds of thousands of them. The owners and operators of container vessels and aircraft are called carriers. There are very few of them.

Shippers and carriers generally do not strike deals directly. Instead, freight forwarders act as intermediaries. They are sometimes described as “travel agents for freight”.

Forwarders purchase space on ships and planes from carriers at wholesale rates, and they bundle together cargoes from many small shippers to fill that space at retail rates, earning a margin on the difference.

The forwarders earn their margin by acting as efficient counterparties for carriers, while providing a full customer service for shippers. They quote rates, arrange door-to-door solutions, handle paperwork and compliance, and step in to solve any problems that arise en route.

Industry structure

Freight forwarding has some attractive attributes.

· Customer relationships can be evergreen, since most shippers have steady, recurring needs to keep moving goods every month.

· Forwarding is asset-light by definition, as the ships and planes are owned by others.

· Barriers to entry are non-existent, but barriers to successful scaling are high. Knowledgeable people and efficient processes are required to provide great customer service at competitive prices.

The result is an industry structure with a handful of global giants, dozens of sizeable regional players, and a long tail of tens of thousands of small, local and niche players.

My table below lists the top 25 forwarders. Many are owned within larger groups, including by carriers such as Maersk and CMA CGM.

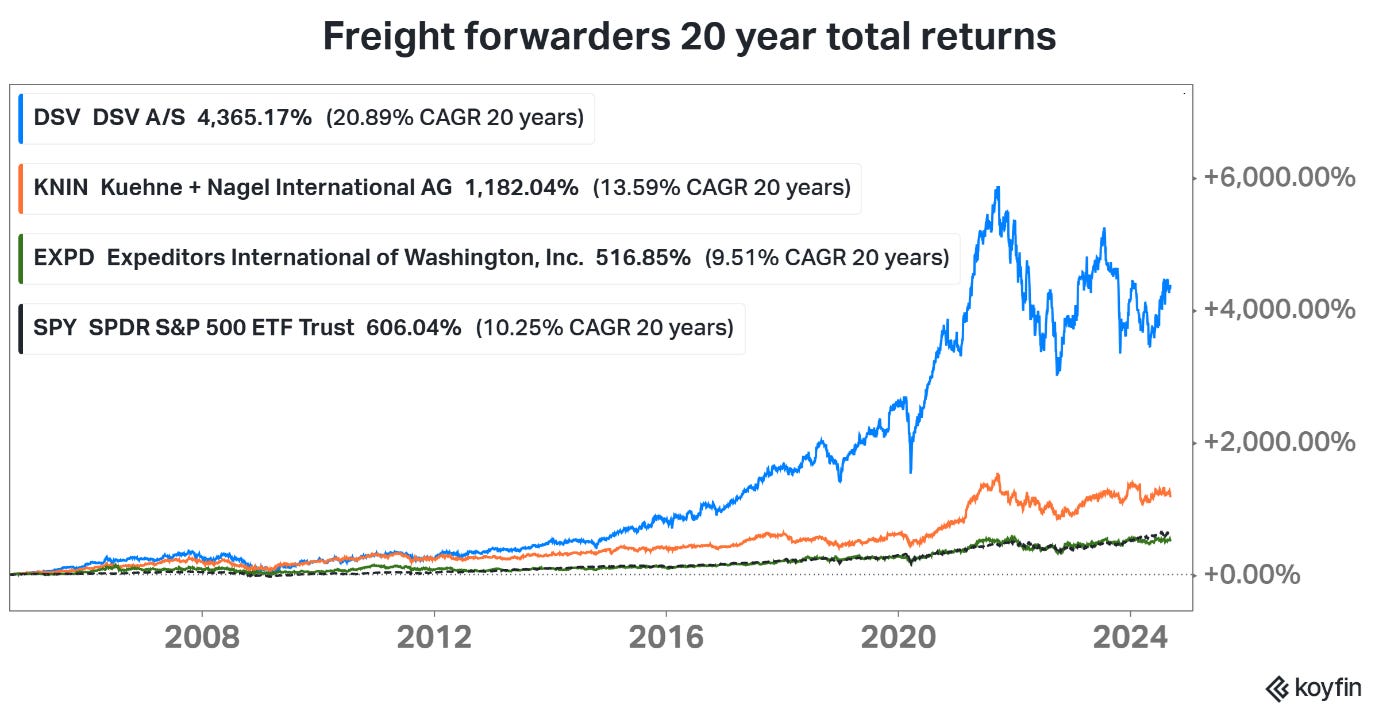

My focus is on the three major pure play listed forwarders highlighted in yellow. These firms all have long histories as public companies. They have each pursued different strategies. All three have generated strong returns, either beating or matching the S&P 500, which has been no slouch over the last twenty years. See my chart below.

My summary table below shows that DSV of Denmark has the highest margin and by far the highest historic growth trajectory, compared to Kuehne + Nagel of Switzerland and Expeditors of the US.

DSV’s success stems from its M&A strategy. It has pulled off a series of ever bigger mergers every few years: ABX in 2008, UTi Worldwide in 2016, Panalpina in 2019 and Agility’s forwarding business in 2021. Now DB Schenker awaits.

This is in stark contrast to Expeditors’ eschewal of any meaningful M&A. Its single-digit organic growth rate makes it less attractive as an investment proposition, especially given a full starting valuation. This is despite its high operational quality.

Kuehne + Nagel has taken a middle ground, with a number of small and medium-sized acquisitions, but no deals at the size DSV has done.

DSV’s ability to integrate major acquisitions depends in part on its mastery of CargoWise. It is counterintuitive that DSV’s reliance on a third-party, standardised software package used by many forwarders is a source of competitive advantage, when compared to the custom-built core systems that K+N and Expeditors use.

DSV profile

My chart shows that DSV has sustained double-digit topline growth for two decades. The freight super-cycle of 2021-22 is clearly visible. 2023 represents a normalised figure for revenue, which has risen 1% year on year in H1’24.

Gross profit, net of cost of carriage, is a relevant figure for freight forwarders. My chart below shows that DSV’s gross profit margin has typically averaged 22%. The recent freight rate volatility sent it to a sky-high 29% in 2023, which is likely not sustainable. In H1’24 the gross margin already fell back by 230bp.

From gross profit, DSV must pay staff costs, external costs (software, rent etc) and D&A, as well as any restructuring expenses taken as special items. This results in operating profit or EBIT. The conversion ratio is EBIT to gross profit, which is a reflection of efficiency.

My chart below compares the conversion ratios of the three forwarders. DSV is the most profitable. It used to sit below Expeditors, but it first drew level and has now handily overtaken it. (The absolute level of K+N is a bit of a red herring, as it has a higher mix of road and warehouse which drives a lower result.)

DSV’s origin as a Danish trucking business could still be seen in 2004, when Road accounted for 74% of gross profit. Today, the Air and Sea divisions contribute 60% of the mix: see chart below. These two segments are globally well spread, with large presence in Americas and Asia. Road and Solutions (mainly warehousing) are 81% Europe-based.

By EBIT, the segment mix is even more skewed to Air and Sea, the most profitable lines of business.

Why is DSV so profitable, especially for Air and Sea? Two key factors are customer mix and IT setup.

Customer mix: DSV caters to small and medium enterprises to a greater extent than its major peers, which pride themselves on handling global corporate accounts. SMEs are potentially more profitable than large customers, if they can be serviced efficiently, as they lack the negotiating muscle to demand the lowest rates.

IT setup: in 2008, DSV selected CargoWise as its corporate standard transportation management system (TMS) for the global Air / Sea business, with initial deployment in Canada. The global rollout was completed in 2012-13. Ever since then, DSV has relied on this standardised cloud software package, which is provided by Wisetech Global of Australia.

CargoWise: the quasi-monopoly supplier of transport management software for freight forwarders

CargoWise can be understood as the equivalent of ERP software for freight forwarding. Every aspect of a shipment, from initial quotation to confirmation, paperwork and compliance, tracking, invoicing, payments and communications with carriers and shippers, can be handled within the software in a highly automated manner. Accounting, financial reporting and collections are also handled. The software allows for an accurate view of how profitable every customer and every transaction is, which can be powerful for eliminating unprofitable lines of business.

CargoWise has a strict policy of no customisations. Any client can request a new feature; if successful, it will be incorporated into the software and made available to all customers. CargoWise has also pursued numerous bolt-on acquisitions, in pursuit of additional capabilities which are then typically rolled into the core system.

This relentless product development means that CargoWise, which launched its first global edition back in 2004, has kept on improving and becoming more powerful.

There are few, if any, third party competitors. Descartes Systems (DSGX) has many adjacent offerings, but does not have an enterprise-level TMS for forwarders. BluJay was a promising potential alternative until it was acquired by E2Open (ETWO) in 2021, since when it has lost its way.

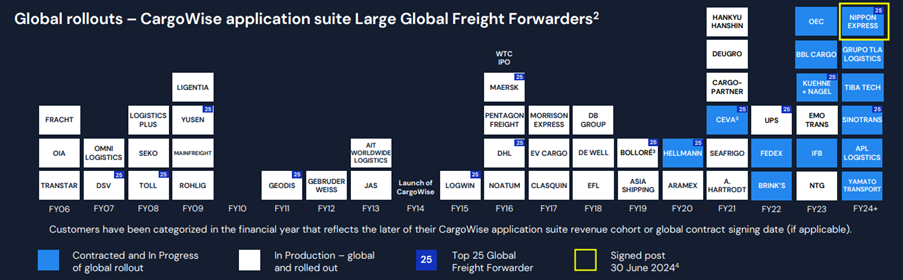

In-house solutions, by contrast, have a poor track record in the industry. Panalpina, Nippon Express and DHL Global Forwarding each lost over a hundred million dollars in failed builds, before writing them off and resorting to CargoWise instead. (In Panalpina’s case, it was acquired by DSV, which implemented CargoWise on its behalf.)

The ultimate cautionary tale was DHL, which is thought to have spent $1bn on its failed system. Its consultant IBM tried to build it a fully functioning modern forwarding environment on top of SAP, but this proved impossible. The write-down was taken in November 2015. DHL immediately signed up with CargoWise instead. By May 2017, the company was announcing the start of its CargoWise rollout to a first pilot country. Global rollout was completed four to five years later.

WiseTech now claims half of the top 25 global forwarders as customers. See its customer roster below. (However, note that K+N has only signed for the smaller customs module thus far, and continues to rely on its inhouse system as its main TMS.)

Expeditors is a holdout. Its proprietary IT system is part of its DNA, and it has no intention of switching to an industry standard system. However, Expeditors’ maintenance of its own system comes at increasing cost. My chart below shows that the company has more than doubled its IT headcount since 2010. IT staff now make up a growing proportion of the total. Roughly half are located in the US, and the others in India.

Comparing staff costs across the three major forwarders, DSV has seen a dramatic improvement since 2016, while Expeditors and K+N remain at around their historic level. See my chart below. I view DSV’s outsourcing of its core IT system as a key driver of this greater efficiency: both directly, in the sense of a leaner in-house IT team, and more broadly, as a superior system allows DSV to run its whole organisation leaner.

DSV’s management

DSV has enjoyed great management stability. Jens Bjørn Andersen was CEO of DSV from August 2008 to February 2024. He joined the group in 1997 with DSV’s acquisition of Samson Transport.

Andersen’s successor as CEO is Jens Lund, who previously served as CFO from 2002 to 2021. In Oct’21 his role was changed to COO and Vice CEO in a clear piece of succession planning.

Lund’s replacement as CFO since 2021 is Michael Ebbe, another fantastically seasoned DSV team member since 2007.

A DSV investment thesis depends on perfect execution of further major deals. It is reassuring that the current top team have been involved together in of all of the past successes.

DSV’s M&A track record

DSV was founded in 1976 as a joint venture of nine Danish trucking companies. Acquisitions in 1989 (x2), 1997 and 1999 moved DSV into the export and international transport markets.

The series of major transforming deals started with DFDS Dan Transport in 2000, followed by Frans Maas of Netherlands in 2006 and ABX Logistics of Belgium in 2008.

DSV has tended to buy mediocre and underperforming freight forwarders. It integrates them into its platform, extracts synergies and transforms their profitability.

UTi of California, a US listed company, had $3.9bn of revenue and was heavily loss-making at the point of acquisition in January 2016. DSV could buy it for just 0.35x sales, even after paying a 50% premium.

UTi’s absorption caused DSV’s margins to dip in 2016. And group revenue rose by only $2.5bn, conspicuously lower than the pre-acquisition run-rate, as DSV shed unprofitable business.

Yet by 2017, the combined group delivered strong sales growth and record high profit margins at every level – amazing stuff. In retrospect, DSV evidently paid a single-digit multiple for the earnings it was able to get from UTi after synergies and integration.

The next major deal was Panalpina. DSV proposed a merger in January 2019, and were initially rebuffed. They agreed a deal in April, which completed in August 2019. This was an all-share transaction with an EV of DKK37bn. For a 30% increase in share count, DSV expected to get a 49% increase in revenue but just a 14% boost to EBIT, given Panalpina’s very low margin.

The outcome was similar to UTi: a dip in margin in 2019 was reversed in 2020, as the combined group once again achieved record high margins and a bigger increase than peers. Ernst Göhner Stiftung, the former 46% major shareholder of Panalpina, continues to hold a c.10% stake in DSV today.

Agility’s GIL was acquired in August 2021 in an all-share transaction, for an EV of DKK27.7bn. The former parent, Agility Public Warehousing Co of Kuwait, continues to hold a c.9% stake in DSV today. It is hard to assess the true contribution of GIL since acquisition, given the dizzying backdrop of the freight price squeeze and profit bonanza.

DB Schenker

As of last week, the press has reported that DSV is one of the two final bidders in the auction for DB Schenker, the fourth-biggest global forwarder and an entity of similar scale to DSV. This would be by far the most ambitious deal yet.

The seller is the German government, and the 72,000 strong workforce is highly unionised. DSV has apparently already promised to limit job cuts to just 1,900. These factors, plus the sheer scale of DB Schenker, might raise doubts as to whether DSV’s usual integration playbook can work in this case.

(In fact ABX Logistics came out of the Belgian state-owned railways, so DSV does have experience integrating an asset of similar heritage. However, ABX came to DSV via a spell in private equity ownership – different to taking control of DB Schenker directly from the state.)

DB Schenker’s financial track record is shown below.

It is not a complete basket-case: the EBIT margin has improved from extremely low (2%) to okay (6%), as shown in my chart below. But this is still half the level achieved by DSV.

In IT terms, DB Schenker is one of the rare cases that is running an in-house developed TMS that works as intended.

If DSV can buy DB Schenker for €14bn or c.0.75x sales, it will rank as a favourable deal, given DSV’s track record of making a success of M&A.

Nothing is confirmed. If DSV does win the auction, then a large element of equity funding would be required. I don’t know if the German government would take DSV shares, or whether DSV would simply raise cash via a rights issue fundraising to institutions.

DSV might yet lose Schenker to CVC, the private equity bidder. A possible Plan B target would be CH Robinson’s international forwarding business, which DSV already mused about bidding for back in June 2022, according to press articles at the time.

DSV estimates and valuation

My estimates below do not incorporate DB Schenker, since there is no assurance they will win the auction. I would regard a deal as positive, given DSV’s track record of delivering strong earnings accretion from year 2 post completion.

DSV is highly cash generative. It is currently using free cash to buy back shares. The gearing ratio was 1.8x at the end of June, consistent with the target level of “below 2.0x”.

Annex 1: DSV’s use of CargoWise

Earnings calls and expert transcripts give good colour about DSV’s use of the software.

On integrating UTi onto CargoWise:

The migration into our TMS IT platform, CargoWise One, it's also on track, and we estimate that by the end of this month, about 1/3 of the users have been transferred. […] On the IT side, on the back-office side, it's clear that UTi had a higher IT cost than we had in DSV, like, even if they were half the size, of course. So there's -- of course, now that we made a lot of the systems redundant, we can let some of it go. [Source: Jens Lund, May’16, four months after deal completion.]

On integrating Panalpina onto CargoWise:

I have spoken to some of the people who've been trained in CargoWise. They are extremely excited about going and moving over to CargoWise. They feel it's a more smooth system to work upon. It makes their life much easier than what it was before. And it's not only replacing what was in place in Panalpina, I think actually CargoWise, in many instances, are superior to what the functionalities that we saw. The fact that you can reuse data in a much smarter way, it is more efficient. I think that is what we can say at this moment in time. [Source: Jens Andersen, Nov’19, three months after deal completion]

[T]he countries that are now working on CargoWise, they represent 60% of Panalpina's volumes. Then actually, what happens when they are moved over, there's a lot of volume that can be moved day one. And some of the volumes will gradually flow over so that it's 100% on the DSV platform. That will take a couple of months before it's all in order. […] And of course, when we can take up the double handling, then we can realize more and more synergies and we get the productivity in line with the productivity that we've been used to in DSV. The Panalpina staff, they will be able to operate just as efficient as the DSV employees. So that's really the journey we are taking on that one. [Source: Jens Lund, Feb’20, six months after deal completion.]

On getting the most out of a powerful software package:

The system itself is one thing. It's always how you use it, correct? So in general, IT systems are used probably 40% in general, complex systems. CargoWise, we probably use mid-70s now.

So we still have room for improvement. [Source: Carsten Trolle, former CEO of DSV’s Air & Sea division, May 2022 investor day]

On the competitive advantage of CargoWise users:

WiseTech customers are just better freight forwarders than their competitors. They really are, so they've been the ones doing all the acquisitions other than the other way around. WiseTech customers buy non-WiseTech customers because they generally are a profitable company and then they can do that, and DSV has gone on the greatest acquisition spree that freight forwarders have ever seen, and so you don't have churn. That's the other thing. Churn is still under 1%. It's like you don't have churn. [Source: former WiseTech executive, Third Bridge, June 2024]

Annex 2: WiseTech financials

WiseTech’s IPO on the Australian Stock Exchange took place in April 2016, piggybacking off the large DHL contract. Trailing revenue for the year to June 2015 was A$80m, and the top ten customers accounted for 21% or A$17m. DSV was one of the top ten customers, and was likely spending a total of A$2-4m at that time… virtually nothing compared to the costs of in-house development.

Since IPO, WiseTech has grown its revenue at a 33% CAGR, as per my chart below. Today’s A$1,042m of total revenue includes A$867m of CargoWise recurring revenue, of which just over half is attributed to the nine Top 25 global accounts that include DSV. My estimate of DSV’s current spend on CargoWise is A$50-80m or USD35-50m, which sits comfortably within its c.USD700m of “other external costs” line.

WiseTech is not only fast-growing but highly profitable. It is perhaps not surprising that the stock trades with a market cap of A$41bn or USD27bn, implying 30x sales, 60x EBITDA and 100x P/E on a next 12 month basis.

Excellent and very useful deep dive on the freight forwarders industry. Thanks for sharing.

Hi Alex, You are missing a few key points. DSV's success has everything to do with its incredible corporate culture and religious focus on ROI. 2 things have changed. 1) The surprise departure of DSV's young CEO and 2) the (simultaneous) inexplicable announcement of the JV with the Saudi Arabian government to develop the logistics infrastructure and provide logistics support for the construction of NEOM - which is a deviation from DSV’s traditional asset-light business model and will require upfront investment (in warehouses, buildings, transport infrastructure) and is an inherently more capital-intensive approach. This is why the stock has derated...is it really the same DSV as the past? Will they really not overpay for DB Schenker? Why did the great CEO quit? William