How did a once obscure group of trucking stocks deliver >1,000% total returns in the last decade? And what are their prospects from here?

Old Dominion and Saia have compounded revenues at 10% for a decade, and earnings at 17-20%, on a purely organic and self-funded basis. The stocks have re-rated from mid-teens multiples to over 30x. XPO has arrived at a similar destination after taking a different, M&A-led route.

In this post I aim to look through both ends of the telescope. First the big picture questions.

-What is the LTL (less-than-truckload) business model?

-Why is industry structure so drastically favourable for the LTL network operators compared to full truckload players?

-What levels of profitability can the LTL industry support on a sustainable basis?

Then I zoom in to understand the individual stocks, the current position in the cycle, and to consider which of the names, if any, make attractive investments right now.

I conclude that the LTL story has further to roll. I’ve started a position in Saia, which I profile in detail. I expect both Saia and ODFL to continue to deliver strong profitable growth, and for the stocks to outperform further.

As always, feedback is very welcome. I am aware these stocks are generally well liked. Where can I find the strongest expression of a bearish thesis on the industry – for example that margins have peaked and will come under sustained pressure?

What is less-than-truckload?

If you want to send a small package up to 150 lbs to anywhere in the 48 states, FedEx or UPS can fly that overnight, often with a 5pm pickup and an 8am delivery.

If you’ve got a whole truckload of widgets to move from A to B, then it will be cheap and easy – over 100,000 truck charter companies will fight to give you their lowest bid.

But if you have to ship something between those two extremes – say 1,000 lbs of goods in a couple of pallets – then you will need to rely on one of a handful of less-than-truckload network operators.

Your carrier will pick up your shipment, group it at the local terminal with other consignments headed in the same direction, truck it overnight to the destination terminal, and then transfer it for the final local delivery – all on a one, two or three day schedule depending how far it’s headed.

LTL is “viewed as something that you’d like to avoid, if possible. It’s relatively expensive compared to truckload and relatively slow compared to parcel, but it’s never gone away. It continues to fill a needed tweener gap in the market.” (Source: Tom Nightingale, CEO of AFS Logistics.)

Customers for LTL are all kinds of industrial and retail firms, large and small. LTL’s freight mix skews more industrial than parcel (dominated by ecommerce) and full truckload (dominated by retailers).

LTL industry fundamentals

LTL is a $60bn industry. In the US, the top 5, 10 and 25 LTL carriers have approximately 50%, 75% and 90% total share of revenue respectively. Only eight national carriers remain, with all others being regional only.

The industry is highly consolidated due to triple barriers to entry.

Capital: a national footprint costs billions of dollars. You need a dense network of strategically located terminals, tractors, trailers and technology assets, as well as thousands of drivers, dock workers and salespeople.

Scale: you need sufficient flows of freight on a daily basis to be able to fill all the trucks on all the different routes to a profitable level. This requires relationships with large direct accounts, 3PLs and freight forwarders, and SME and spot business.

Quality: to stand any chance of being competitive, you need the experience and expertise to operate one of the most operationally intensive businesses that exists. Delivering goods on-time, safely and reliably, while also designing the network to run profitably, and making the right commercial decisions to balance price vs volume, all turns out to be incredibly difficult.

Industry profitability

My chart below shows profitability for the major listed LTL players. (Transport industry practice is to use the operating ratio, which is simply 100% minus operating profit margin.)

Prior to the financial crisis, and despite the hot economy, LTL firms had mediocre operating ratios in the low 90s, or at best the high 80s. The Great Recession knocked many firms into losses. And from 2010 onwards, there’s been a secular increase in profitability, especially for the four big listed non-union players. (Yellow, the biggest union carrier, ceased operations and filed for bankruptcy in July 2023 – see below for details. ABF, owned by ArcBest, is also a union carrier.)

Labour is the biggest cost item, given the high-touch nature of LTL service with the multiple loadings, unloadings and transhipments required.

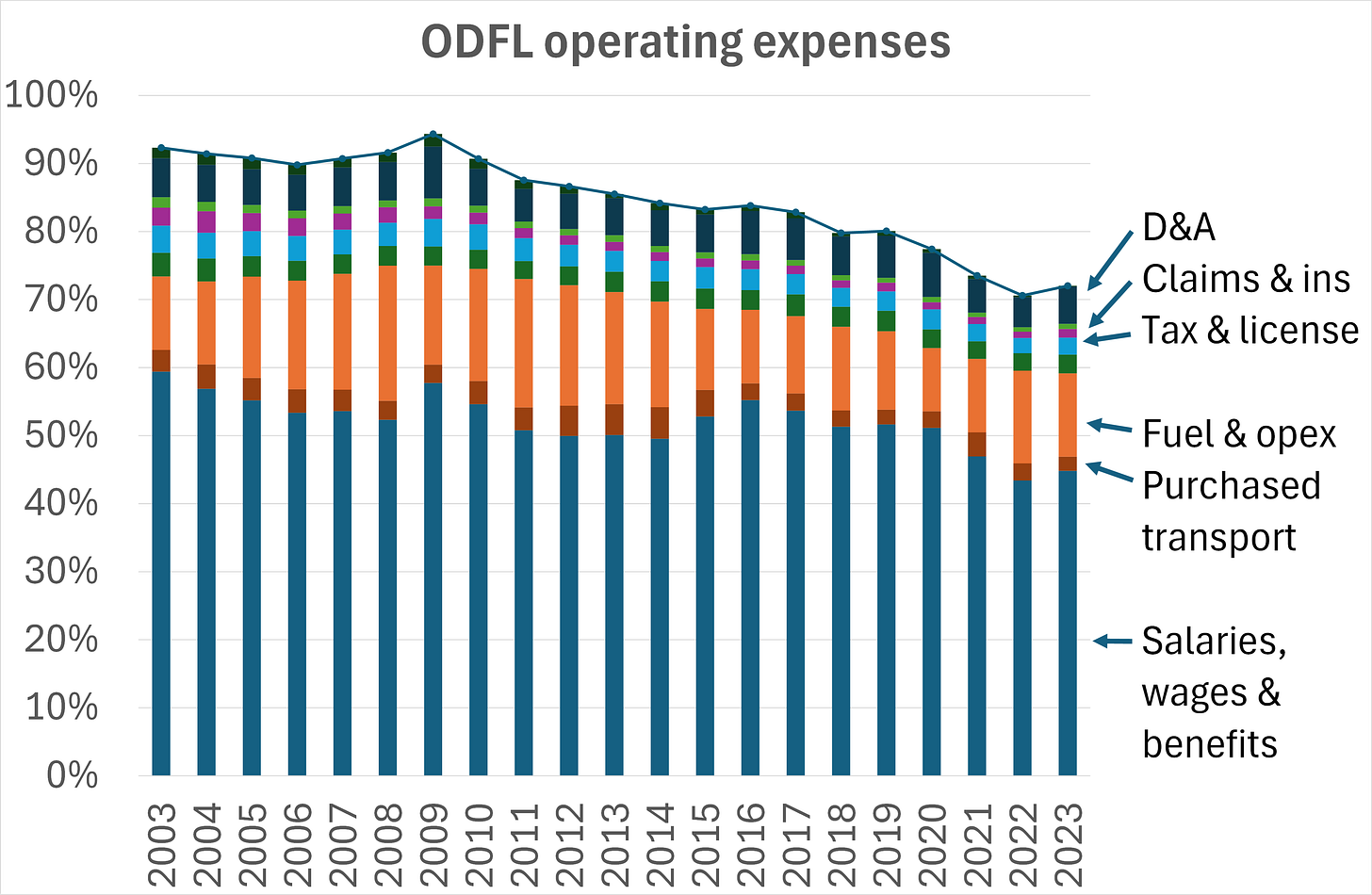

The chart below shows Old Dominion’s cost breakdown as an example. From this we see that falling labour cost as a proportion of revenue has been the main driver of ODFL’s wonderful profit progress.

The fall in the labour cost ratio does not arise from nickel-and-diming the staff. ODFL looks after its drivers and other workers well, and has outstanding retention.

Instead, a virtuous circle of quality improvements, higher prices and market share gains is at work. This drives network densification, with more freight moving through ODFL’s semi-fixed cost base. ODFL can then invest heavily in increased capacity and further quality improvements, keeping the progress going.

The nature of competition – quality-led and oligopolistic

LTL carriers do not all deliver an identical service. Differences in service levels can be substantial between carriers, in ways that matter to customers. Speed (do they offer 24hr or 48hr for a given route?), reliability (on-time could vary from 90% to >99%), and risk of damage to freight are key variables that are more important to most customers than price.

A consultant called Mastio produces closely-watched annual quality rankings, based on over a thousand calls with customers. The strongest carriers publish their own statistics for on-time performance and claims ratios, while weaker carriers don’t. Customers take note, and pay different prices accordingly.

LTL carrier CEOs are vocal about investing in improved quality, and getting paid for this via increased rates.

Competing on quality rather than price is a favourable dynamic for producers – see also the market for IPO banker syndicates or Magic Circle law firms.

The quotes below give a flavour of the strength of price discipline in the industry.

“There are some people on the periphery who are more aggressive when it comes to pricing, but generally all the large carriers are disciplined,” Christopher Jamroz, executive chairman and CEO of long-haul LTL carrier Roadrunner, said in an interview. “The major LTL carriers have had to learn to be disciplined.”

“The LTL market’s surprising profitability and ability to not only exist, but to become the most lucrative and well-managed niche of the overall trucking industry, is astounding to even veteran leaders in the sector.” John Schulz

There is a pleasant scent of oligopoly about the LTL industry. The firms habitually announce annual GRIs (general rate increases), in a manner that checks several boxes in the price signalling checklist. The quote below gives details.

“[O]nce a year they’ll talk about their GRIs. GRI is general rate increase, and the guys do one GRI a year. They normally announce it in November or December, and it’s always 5.9%. It’s funny because everybody waits, they all wait for FedEx or UPS to come out first. FedEx and UPS come out first every year. They announce their GRI for their LTL business. It’s always just under 6%. It’s 5.8%, 5.5%, 5.9% and then all the smaller guys come out right afterwards and they say they’re doing the exact same thing. That is the rate that applies to all of the non-contracted business.” (Source: Saia’s former CFO, Third Bridge interview, June 2021).

Published tariffs do not equate directly to achieved pricing, given the widespread use of large volume-linked discounts in individual contracts. Nonetheless, the net outcome has been significant increases in achieved price for many carriers, alongside improved quality metrics.

My chart below shows that all publicly traded carriers achieved price hikes in the last four years. ODFL and Saia are distinguished by having also increased their price positioning throughout the 2010s, while FedEx and Yellow were flatter in that period.

These price rises have sustained the near-record profitability we saw above, despite the freight recession that started in mid 2022.

Union firms and Yellow’s bankruptcy

Union vs non-union is a key distinction among LTL operators. Yellow, UPS (now TForce Freight, owned by Canadian TFII) and ABX Freight were the notable union operators, negotiating five-yearly contracts with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

Yellow was the #2 LTL player by revenue behind Fedex, and a long-term market share donor. As a union player, it had high costs and poor service quality. It compensated by offering lowest prices, which drove a vicious circle of low profitability and underinvestment.

The stock peaked at $3bn market cap way back in 2005, and already by 2010 Yellow was down 99% from peak. Amazingly the company was kept on life-support and remained listed and operational right through until the final moment of death in mid 2023, when all operations ceased.

The exit of Yellow is a major event for the LTL industry. Overnight, its substantial freight volumes were forced to shift to other carriers. The bankruptcy court auctioned off Yellow’s hundreds of real estate locations, with XPO, Saia and Estes each buying dozens of terminals.

In the short term, the removal of Yellow’s capacity was well timed to bolster volumes and profits for other carriers, amid the freight recession that has been ongoing for at least 15 months.

In the longer term, the impact is less predictable. In the coming months, many of the auctioned ex-Yellow terminals will be brought back into service by their new owners after refurbishment. The net industry capacity reduction that results from Yellow’s exit may end up being relatively modest. On the other hand, the removal of the large price-oriented player and its replacement by more quality-focused and price-disciplined operators may bode well for industry margins.

Secular or cyclical?

The key question for LTL stocks is whether operating ratios can keep on improving in the mid to longer term. My answer is yes. In my view, the industry overall will be able to sustain a quality-led paradigm in which overall service quality, pricing and profitability all have further to run. Old Dominion and Saia in particular are well placed to lead the way on quality, price and profitability thanks to their organically built networks, strong management teams and firmly entrenched cultures.

Unlisted players unlikely to be disruptive

Among the national carriers, Estes Express and R+L are privately held, with minimal financial disclosure. The same is true of most large regional carriers. These are solid, family-owned businesses which are following the same template of investment in service quality, price discipline and a focus on profitability. Many of the unlisted players have substantial real estate activities. Private equity is not active in the LTL industry.

M&A is not a winning strategy in LTL. A high-integrity network is best built organically and rather gradually. In a merger, one plus one equals less than two due to unwanted duplication of terminal locations. And a high-functioning LTL business is a well-oiled machine that could be knocked off course by a change of ownership, change of strategy or integration of a separate business with a different culture.

Stock selection – better to travel or arrive?

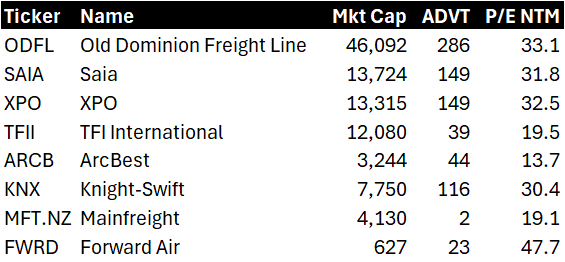

The two most attractive LTL pureplay stocks are Old Dominion Freight Line (ODFL) and Saia.

Old Dominion is a $46bn market cap with industry-leading service quality and profitability, distinct family ownership and culture, and a decades-long track record of excellence.

Saia is a $14bn challenger that struggled for years as a regional player with indifferent quality and profitability, until it started on a dramatic improvement path about eight years ago.

Both stocks trade on a similar current multiple of c.32x 2024E P/E. Consensus also expects similar earnings growth for both in the next 2-3 years. The choice is a matter of taste between an established industry leader versus a challenger that could have higher long-term upside potential if it narrows the gap.

I plump for Saia, but would happily own either name. Further details are below.

XPO is a little less attractive to me. It has significant net debt, unlike ODFL and Saia. And its unwanted European business is a drag on profit growth and dilutive to quality. (XPO previously announced it would divest the Europe division to become a US LTL pureplay, but in Dec’22 it changed its mind given weak European markets.)

TFII looks like a higher-risk bet given the challenges of turning around the ex-UPS union-run business it acquired in 2020.

ArcBest (ARCB) looks unattractive given its union status and significant non-LTL activities.

Knight-Swift (KNX) is mainly a truckload business that has entered LTL via acquisition, but has not yet demonstrated it can win.

Mainfreight is an outstanding New Zealand-based air and sea freight forwarder, which also has strong trucking operations in NZ and Australia. In the US they are quixotically engaged in trying to build a national LTL carrier from scratch. Evidence of progress to date is minimal. (Overall Americas revenue is $960m, which includes air & ocean forwarding and warehousing. Mainfreight does not appear anywhere in the published Top 40 rankings which cover players down to $66m of LTL revenue.)

This stock serves as an interesting test case for my thesis that the barrier to successful entry into the US LTL market is extremely high, even for a patient, determined, capable and well-funded would-be entrant.

Forward Air (FWRD) used to be a reasonable quality player in expedited LTL. Now the stock is mainly a joke. Management signed an appalling acquisition agreement with private equity last summer to buy a freight broker for $3bn, then immediately regretted it and tried to back out, but were forced to complete the merger this January against their will, Elon-style.

Saia

Saia was founded in 1924 in Louisiana. By the mid-1980s it was a strong regional LTL carrier in the Southeastern states. In 1993 it was acquired by Yellow, and then merged with three other businesses by 2001 to reach coverage in 21 states. Yellow spun off Saia in 2002 due to conflicts arising from its non-union status and increasing competition with Yellow’s core business. The acquisition of Clark Bros in 2004 expanded coverage to 30 states. Final acquisitions in 2007 took them to 34 state coverage, which remained the case until 2016.

In 2017, Saia embarked on an ambitious organic expansion into the Northeast. My map below shows the existing network in red, and the new post-2017 locations in other colours.

Saia is now ranked #7 or #8 by revenues – one of the newest and smallest national players. Customers are split 50:50 between large firms on bespoke contracts and smaller customers on the general tariff. The logos shown below reflect a mix of industrial and retail customers.

At the same time as expanding in the Northeast and achieving full nationwide coverage, Saia has been working hard to increase its quality metrics. Below is the improvement in the Claims ratio (cost of damaged freight as % of revenue).

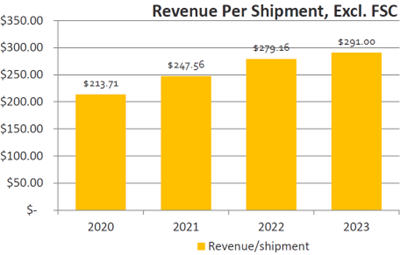

Saia has used its improved coverage and quality as justification to ask for price increases. It has been successful in that endeavour, as shown below.

The result has been a step change in profitability, most dramatically in the last three years.

Saia has reinvested steadily back into its network to keep the flywheel spinning. The chart below shows capex reached $437m in 2023.

ROIC is north of 20% at current operating profitability, so the opportunity to reinvest into the network represents strong value creation.

In 2024 capex will be a billion dollars, thanks to Saia’s purchase in the Yellow bankruptcy auction of 28 terminals to further expand its footprint. These are shown on the map below.

The Great Plains locations will allow Saia to go direct instead of partnering with agents. And Laredo, Texas is well located for Saia to grow its north and southbound Mexico cross-border services, leveraging its new partnership with Mexican LTL Carga Express.

Saia’s balance sheet is strong, with $157m of net cash at the end of 2023. Saia will comfortably be able to fund the high 2024 capex from cash flow and debt.

Saia’s cost structure is shown below.

As with the ODFL cost breakdown shown above, labor is the major cost item. Improved quality and higher pricing is the key driver for more efficient utilisation of the workforce, and therefore higher profitability.

Saia uses an element of purchased transportation within its model. This can add flexibility to the network, for example it may make sense to charter a truck if Saia only has a one-way freight flow between a certain city pair. Saia also makes use of railroads at weekends where consistent with delivery schedules, in order to save on costs.

Management continuity has been excellent at Saia. Rick O’Dell was CEO from 2006 to 2020, having joined the firm in 1997. He was succeeded by Fritz Holzgrefe, 56, who had joined Saia in 2014 as CFO. The CFO and Chief Customer Officer also have 10 and 26 years of Saia tenure respectively.

The near-magical achievement of Saia management in the last few years has been to expand the network, improve quality metrics and increase profitability, all at the same time. New organic terminal openings should bring unabsorbed start-up costs, and potentially also teething problems related to hiring, training and quality of service. But none of that has visible in Saia’s numbers, as steady improvement in the core network has more than offset it.

In an example of making their own luck, Saia was helped by the bankruptcy of $400m Northeast regional player New England Motor Company in February 2019. NEMC was unionised, and suffered two years of big losses before closure – doubtless in part due to Saia’s entry into the region from 2017. Saia was then able to pick up leases on several of the NEMC terminals to assist their expansion.

Closing the gap to ODFL

As at Dec’23 Saia had 194 terminals compared to ODFL’s 260. Saia’s revenue is less than half of ODFL’s, so it is clear that Saia’s revenue per terminal is far lower. Saia is addressing subscale terminals with rebuilds and replacements in key locations that are causing bottlenecks.

Saia has work to do to match ODFL in key metro areas. The example below shows Atlanta. In 2019, ODFL had five terminals around Atlanta (in green on my map below) and Saia had just one. In 2021 and 2023 Saia opened new terminals to the northeast and northwest of Atlanta to relieve the pressure on the original downtown terminal. ODFL still looks to have the edge in the Atlanta example for now.

Cyclical considerations

As mentioned above, industry freight volumes have been in recession since mid 2022. Pricing and profitability have held up remarkably well despite this, both for Saia and peers. Yellow’s bankruptcy has certainly helped, as well as the industry’s strong price discipline and ability to achieve higher prices to cover the costs of maintaining high service quality.

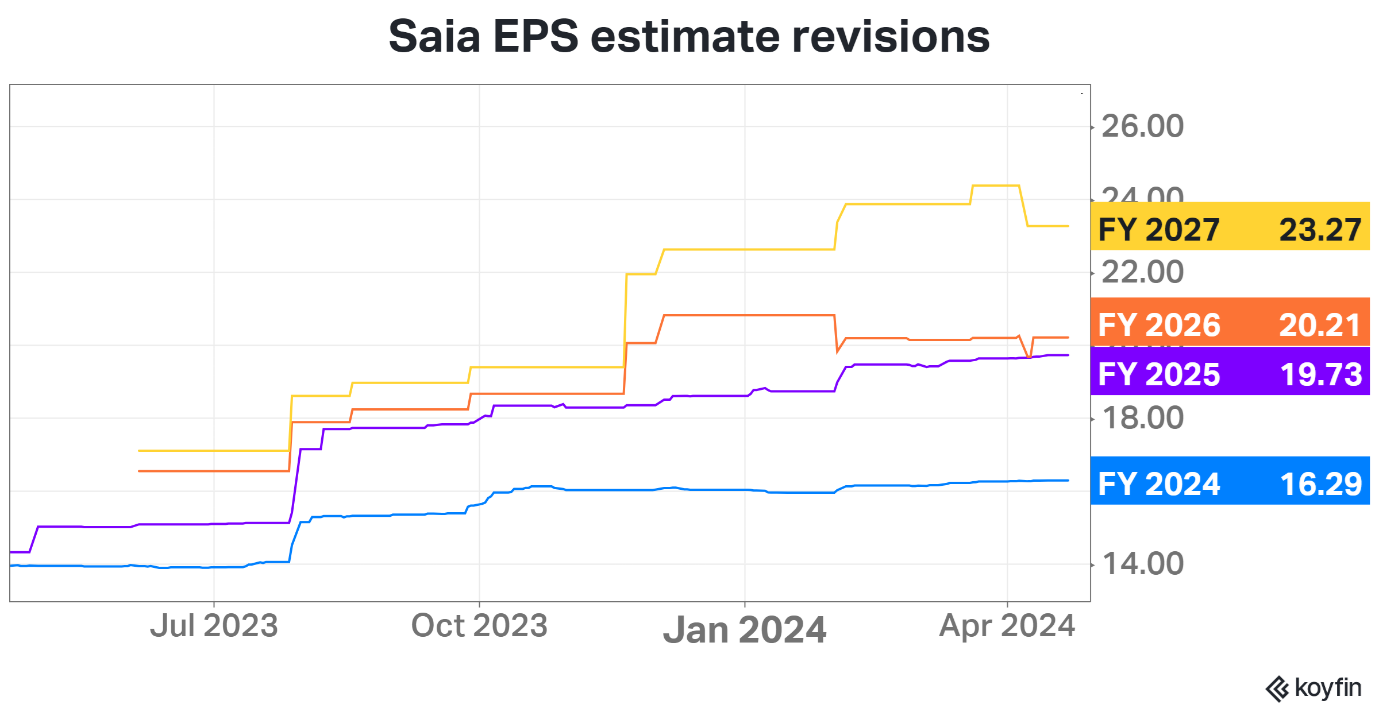

Saia’s management issued bullish guidance on their Q4 conference call at the start of February, calling for 100bp to 200bp of OR improvement in 2024, with the 100bp deliverable even in a continued soft environment. They backed this up with a healthy February figure of +11% tonnage per workday growth on a yoy basis. Saia has maintained positive forecast momentum throughout the current freight recession, as shown below. Their own network-led growth insulates them from the cycle, compared to other LTL players who have seen downgrades.

Forecasts and valuation

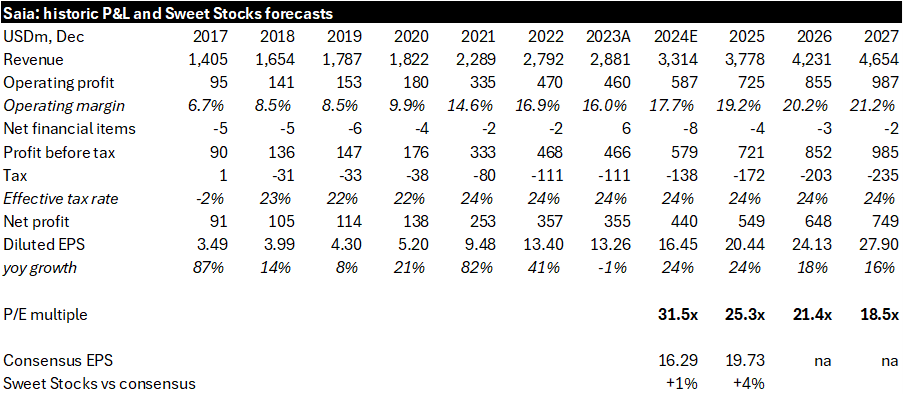

As discussed above, I am sanguine about Saia’s earnings outlook. My estimates are shown below.

Valuation is not discounted, but I take the view that industry structure will support higher-for-longer profitability. I forecast a 20% earnings CAGR from 2023-27E, which would allow Saia to grow into its valuation pretty quickly.

Saia is due to report Q1 results this Friday, April 26. Before that, industry leader ODFL will report on Wednesday, April 24. I will likely comment on Twitter.

Really great read.

I am writing this up presently and this was a fantastic resource.

Merci

Do you have any view on the unit economic of the LTL industry?