I spoke to the Vice President of Shimano’s Accounting Department in preparing this report. All opinions and estimates are solely my own responsibility.

Shimano is the dominant world leader in bicycle components. This market position has sustained profitable growth at 6-7% a year for the past two decades.

From 2020, Covid triggered a boom and bust demand cycle from which the global bicycle market is only now recovering.

Shimano has a US competitor, SRAM, that has grown faster than it and taken market share since 2010.

Electric bikes represent a fundamental shift in technology. Shimano’s market share in the fast-growing e-bike market is far smaller than in conventional bicycles.

Having completed the research process, I expect Shimano to slow down in the years ahead. As such, at 23x forward P/E, the stock looks a bit too pricey for me. I have not bought the shares for the time being.

Feedback is welcome as always.

Background and management

Shimano was founded in 1921 by Shozaburo Shimano, a 26 year old knifemaker’s apprentice. Sakai, Osaka was an area famous for its gun and knife manufacturing. This metalworking expertise translated into high precision bicycle parts.

In 1966 Shimano signed its first European distributor, Paul Lange, who flew to Japan to seal the deal. The flight was worthwhile: Paul Lange remains Shimano’s largest customer today, at 10% of group sales.

By the end of the 1970s, Shimano and its Japanese peer Suntour were selling cheap chains, sprockets and derailleurs across Europe.

Shimano then began its march upmarket, defeating the western incumbents such as Sturmey-Archer and Campagnolo by a combination of better quality-value and genuine innovations.

Shimano’s first Tour De France victory came in 1999 with Lance Armstrong. They have won 19 of 26 since then, including a clean sweep in 2017 when teams using Shimano Dura-Ace won every stage and jersey.

Shimano’s three sons Shozo, Keizo and Yoshizo Shimano served in turn as the second, third and fourth presidents. Yoshizo became president in 1995 and restructured the business processes, with an emphasis on Six Sigma.

Today, the third generation Yozo Shimano is Chairman and joint CEO, while the fourth generation Taizo Shimano is President and joint CEO.

The family remains fully in control of the company, even though their combined ownership stake is just 12%. The next generation is already being groomed: Yozo’s son Yuzo Shimano and Gozo Shimano are both moving through the ranks.

Family politics can be brutal. Kozo Shimano, the grandson of Shozaburo, grew up in America and worked for Asics Tiger in California before joining the family business. He led Shimano American from 2000 to December 2006. In 2008 he was dramatically ousted from the business and cut off completely.

Potential investors should know that Shimano behaves like a private company, showing even less inclination than the average Japanese company to listen to feedback from minority shareholders.

What exactly does Shimano sell?

Shimano’s two divisions are bicycle components (77% of sales) and fishing tackle (23%).

For bikes, Shimano sells all the mechanical parts needed to make a bicycle work. This includes derailleurs, cassette, crankset, bottom bracket, chain, shifters and brakes – together known as a groupset.

A complex product line-up offers multiple quality and price points across the different bike categories, including road bikes, mountain bikes, gravel bikes, e-bikes and “lifestyle” (cheap bikes for casual use).

The most expensive groupsets cost well over a thousand dollars per bike, while the cheapest set of components for a bike-shaped object would wholesale at well below a hundred dollars.

Beyond mechanical components, Shimano also sells a wide range of other products and accessories, including shoes, helmets and clothing.

By revenue, components for high priced bikes make up about 60% of the total, with mid class 25% and entry class just 15% of sales. In volume terms the ratio is reversed, i.e. 15% of volume is for the high end, 25% for mid class, and 60% for the low end.

70% of bike components are destined for new bikes, while 30% goes to the aftermarket.

By category, the revenue split is 40% for mountain bikes, 25% for road bikes, 10% for e-bikes, and the rest includes all kinds of accessories and apparel.

Success factors

Over the last 40 years, Shimano developed a series of innovations that massively improved the performance of bicycles. They made ever stronger, lighter and more affordable systems, that delivered fast and reliable gear changes across a wide range of ratios. Bicycles today are far better to ride than equivalent priced ones from the past, in big part thanks to Shimano’s advances.

Shimano’s major recent innovations include electronic gear shifting which it launched in 2009. Campagnolo followed in 2011, and SRAM only in 2016, after a period of resistance to the concept. Hydraulic disc brakes were another major launch in 2013.

Will future innovations be of equal commercial significance? This is a key risk area, in my view.

Meanwhile, the bicycle market itself has grown in waves and crazes over the years, with 2014-15 as the previous boom years before Covid. Middle-aged men in lycra (MAMILs) have become a force to be reckoned with, ready to spend serious money on speedy and lightweight bikes. Participation has grown in triathlons such as Ironman. These hobbyists matter more to Shimano than commuters and casual cyclists, given the importance of the high end for sales and profits.

Results

All this has delivered a 5% sales CAGR over the last twenty years in yen terms, as shown in my chart below. This is respectable if not earth-shattering growth, sustained over a long period, and ending at what looks to be a cyclical low point.

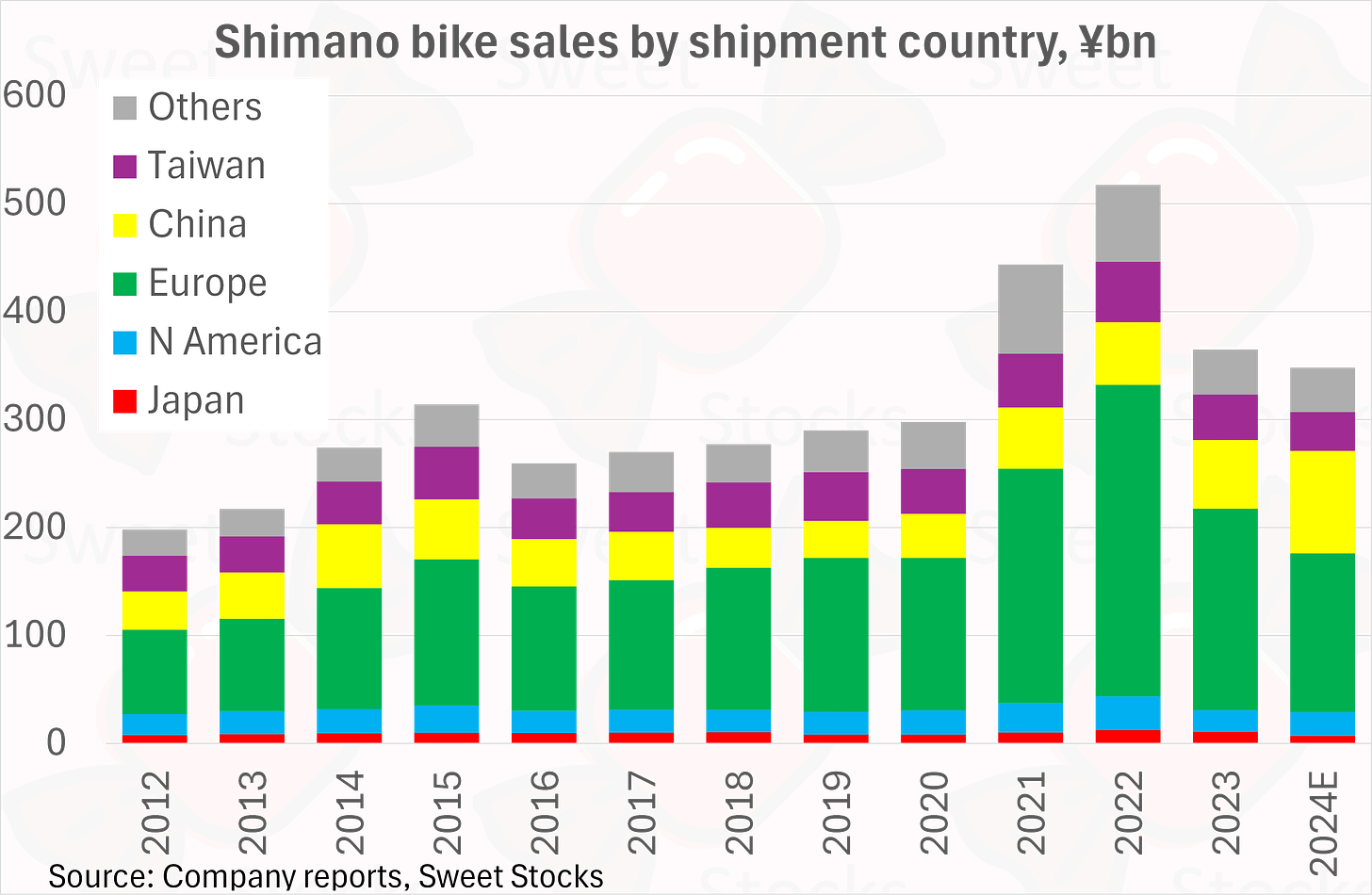

Shimano discloses a split of bike component sales by shipment destination, which I show in my chart below. By this measure, Europe accounts for roughly half of total sales, while North America is tiny at just 6%.

However, the above data reflects where bikes are assembled, which is mainly in China, Taiwan and other Asian countries, as well as in Europe (especially eastern Europe). On an end-user basis, Europe is the clear majority of sales, while North America is about 15%, and other countries are small.

Market share and competition

Shimano’s closest competitor is SRAM, a US business founded in 1987. SRAM is family owned. Like Shimano, it provides full groupsets of gear systems, brakes and all related components. SRAM targets mainly the top end and middle end, with little presence in the mass market where Shimano dominates.

Back in 2011, SRAM filed a form S-1 for a proposed IPO which was later shelved. Revenue in 2010 was $524m. This was split 67% original equipment vs 33% aftermarket. By product line, the split was 62% mountain bike (its origin), 26% road (introduced in 2005) and 12% casual (“pavement”). The sales split by customer location was 15% US, 34% Taiwan, 12% Germany and 38% Other. OP margin was 19% in 2010.

According to Moody’s, SRAM’s 2023 revenue was $1.09bn, for a 5.8% CAGR since 2010. (This would include some acquisitions as well as organic growth.) EBITDA margin was still above 20%, even in a May’24 update that took demand headwinds into account.

Shimano’s bike segment sales grew by 6.2% pa from 2010 to 2023 in yen terms. But the yen collapsed during this period, from Y87 to the dollar in 2010 to Y141 in 2023. In USD terms, Shimano’s bike sales CAGR was just 2.2% in this 13 year period. Shimano’s two-company implied market share fell from 79% in 2010 to 70% in 2023.

Campagnolo of Italy is a tiny rival at the top end, with maybe $120m of sales. Despite a record-breaking 43 Tour de France victories, its long-term decline was already obvious in 2011, and has not reversed since then.

At the other end, Microshift of Taiwan and L-TWOO of China provide low-priced competition. (E.g. Decathlon use a Microshift groupset for their low-priced £599 road bike.)

In electric bike drives, Shimano is a small player in a fragmented market. Bosch, Brose, Yamaha and some capable Chinese companies are all forces to be reckoned with.

The bicycle cycle

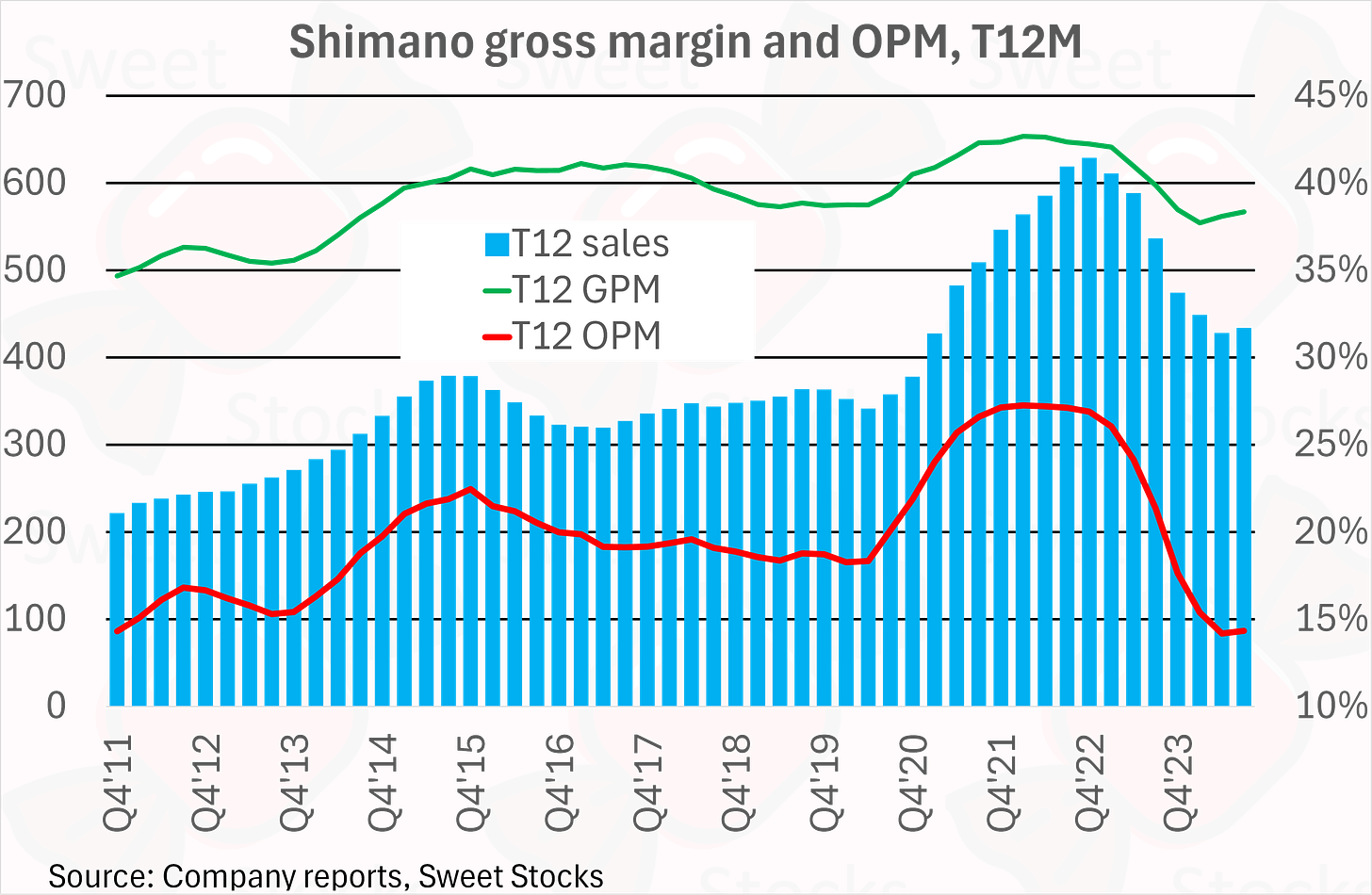

My chart below shows quarterly sales and margin for the bike segment. Already from the September 2020 quarter, demand started to jump, as part of the Covid-related boom in leisure equipment of all kinds. Peak sales came in the Sep’22 quarter, with a sharp collapse since then. The trough was in Dec’23.

The smoothed, trailing 12 month version shows sales and margin both poised to inflect on that metric. A 92% spike was followed by a 38% decline.

Shimano’s experience was mirrored by the whole industry. My chart below shows sales for Shimano and three Taiwanese listed peers. Merida and Giant are Shimano’s customers, while KMC is a competitor in chains. All four firms have seen broadly similar sales swings. Shimano and KMC, as suppliers, may be seeing a slower recovery due to a more pronounced bullwhip effect as inventory moves through the supply chain.

To Shimano’s credit, they avoided the temptation to add huge new capacity at the peak. Capex across 2021-23 was lower than the preceding three years, which is unusually disciplined for firms that were caught up in Covid booms.

Nonetheless, they did add incremental capacity within their existing factories. (They manufacture in Japan, Malaysia, China, Singapore, Philippines and Czechia.) Today they are experiencing lower than normal utilisation, which is depressing the gross margin by a couple of points compared to the normal level – see my chart below. The operating margin is more depressed by around five points, given operating deleverage suffered on SG&A costs as well as the impact of wage hikes.

Shimano hiked its prices in 2021-23 to cover inflation of raw materials. This was a departure from normal policy to leave prices for existing products unchanged after launch.

Specifically, in 2021 Shimano raised prices for overseas made products by 5% on average. In 2022, it hiked Japanese made products by 5%. In 2023 all prices were raised by a further 5%. The cumulative 10% hike appears to have been insufficient given the sharp OP margin decline.

Fishing tackle

Shimano’s performance in fishing tackle has been stronger than in bikes, although at 23% of sales, the division is not big enough to move the needle. There’s a clear synergy given the mechanical precision required by the fast-spinning fishing reels that feature gears, brakes and high-performance materials.

Fishing has grown faster than bike parts in the longer run, and the segment margin has been significantly improved from c5% to the mid teens or better. See chart below.

The fishing market is more fragmented than for bike parts. Daiwa, owned by Globeride (7990.T) is the closest like-for-like competitor. Its fishing sales have been slightly higher than Shimano’s, but its profitability is far lower.

US-based Pure Fishing is a similar-sized rival to Shimano. Newell Brands sold Pure Fishing in 2019 for $1.3bn to PE firm Sycamore Partners. Rapala VMC of Finland is an $84m microcap that has seen sales and profits fall far below the pre-Covid level.

Financials

Shimano’s free cash conversion has been lumpy from year to year. Cumulatively it reached 79% from 2010 to 2023 inclusive: see chart below.

R&D expense included within SG&A was Y14.6bn in 2023, or 3.1% of sales. Advertising expense was also 3% of sales.

Shimano’s inventory to sales ratio should normally be 18-19%, but is currently 26%: see chart below. The company is confident that all the inventory is sound. They see December as the timeline for completion of inventory adjustment of new bikes in the marketplace. Meanwhile, the inventory of spare parts in their own distributor network will be reduced gradually.

Return on invested capital has averaged 12%, which means Shimano has been adding value over time. See chart.

This is despite carrying an ever-growing net cash pile (see chart, now 26% of market cap), which mechanically suppresses the ROIC by several percentage points, compared to the counterfactual where Shimano pays all the cash out to shareholders.

The dividend payout ratio has averaged just 28%, which explains why cash has piled up. In the last three years, some share buybacks have doubled the total payout ratio to around 60%, still too low to avoid cash piling up further.

Interestingly, a heavier buyback programme in the decade from 2000 achieved a 31% share count reduction, but in the most recent fifteen years the company has been far more reticent.

Under de facto family control, my best guess is that Shimano will continue to hoard its cash indefinitely. Any sudden change of heart would deliver immediate upside.

Estimates and valuation

On my estimates, Shimano trades on 23x 2025E earnings. This does not seem especially cheap, given the obvious risks that recessions and/or tariff disruptions could impact the hoped-for recovery. See below.

Shimano has historically traded anywhere from 15x to 30x. The current multiple does not look cheap versus its own history.

Great write-up on a great company. In my humble opinion Shimano has the best price-to-quality-ratio in the bicycle space, kind of similar to Toyota. Shares are not that interesting though. Low dividend yield, too much net cash, few buybacks. Could get interesting at a lower price...

Thanks Alex. A great article, well done. For my penny's worth, I'll just sit and watch.