Spirax is a UK engineering firm with a long track record of profitable growth as a global steam systems specialist.

Since 2016 the business profile has changed significantly. Bioprocessing and semiconductor exposures blossomed alongside the traditional industrial process markets. A major wave of M&A further accelerated growth. In 2021 COVID vaccines boosted sales even higher. And Spirax was positioned as an ESG champion that could help its customers reduce their energy use and transition to net zero.

This heady cocktail of positives saw the stock spike up to an exuberant 50x valuation in 2021, with a c.$17bn market cap at peak.

Since then, the stock has unwound much of the excitement. Post-COVID destocking and industrial slowdown have knocked 25% off estimates and 50% off the USD share price. The stock has de-rated to a more palatable 28x 2024E P/E. (See chart below.)

Is there an opportunity in Spirax? I started this post hoping so. However, my research uncovered a number of risks that may not be appreciated by consensus.

Spirax’s most profitable and fastest-growing business, in bioprocessing, is set to face a new competitive challenge from $38bn market cap Ingersoll Rand. Last month they announced a $2.3bn acquisition with the specific stated rationale of disrupting Spirax’s niche of integrated peristaltic pump and tubing solutions. As far as I am aware, this news has gone uncommented by analysts covering Spirax.

The Electric Thermal Solutions business area remains unproven after difficulties bedding in the series of big acquisitions. Spirax’s key listed US competitors are performing better yet trade at lower multiples.

The core Steam business has performed robustly to date, but it may be maturing. Its outlook for mid-single-digit organic growth could disappoint higher expectations at group level.

Considering these challenges, alongside the still demanding valuation, I prefer to stay on the side-lines for now. I’ll continue to monitor Spirax for a possible entry point down the line.

Background

Spirax-Sarco was floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1959. The Spirax and Sarco names have been synonymous with steam traps and associated steam control products globally for over a hundred years. Spirax has documented its history dating back to 1888. All 178 pages can be read online, or the company will send you a hardback copy on request.

A theme of the book is that Spirax has been concerned throughout its history to preserve its independence. This seems to be a key motivating factor for management.

“The policy adopted by successive generations was to make sure the business continued to grow: a strong Spirax Sarco was the best defence against any unwanted interest from outsiders.”

Spirax is currently undergoing a management change. Nick Anderson stepped down in January 2024 after ten years at the helm, replaced by CFO Nimesh Patel. Nimesh joined Spirax in 2020 from a head of corporate finance role at Anglo American, and previously spent 14 years as an investment banker. He is presumably at ease with deal-making, but is perhaps less proven as an operational manager of an engineering firm.

Louisa Burdett will join in July from Croda as the new CFO.

Steam Thermal Solutions

Steam is Spirax’s original business, and still the biggest. From 88% of total sales in 2000, it is down to 54% today, as shown in my chart below. The most interesting debates on Spirax as a stock relate to the two other divisions. But the continuing health of the steam segment is foundational to any potential buy case, so it’s worth spending the time to review Steam first.

Steam has multiple industrial uses for heating, cleaning, sterilisation, hot water generation and humidification. Spirax’s products include steam traps, control valves, condensate recovery pumps, strainers, separators, flowmeters and boiler controls. The diagram below illustrates their use.

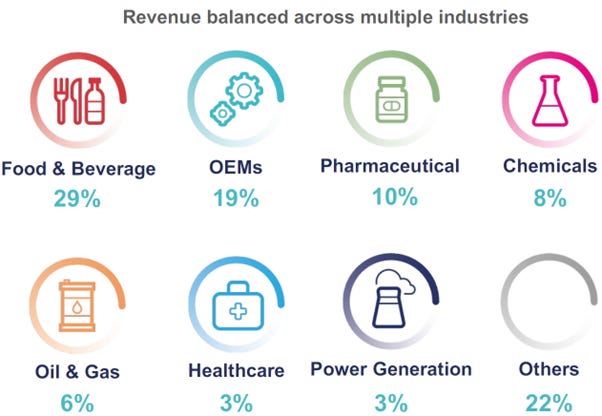

The sectoral split for Spirax’s steam sales is shown below. There’s a balance of defensive as well as cyclical end markets. (OEMs are equipment makers who assemble Spirax components into their own machines for sale to end customers.)

Spirax’s steam business has outperformed the mature underlying markets it serves. The chart below, from Spirax itself, shows the Steam organic growth from 2002 to 2022 ran at 1.9x the (very sluggish) industrial production growth in its markets.

Spirax are coy about providing the actual figure for Steam’s organic growth rate over the whole period. My own chart below shows that at group level, organic growth averaged a respectable rate of 5.7% from 2000 to 2023 inclusive. Watson-Marlow has averaged 9% or higher organic growth throughout this time, meaning that Steam’s organic growth rate has averaged c.5%. Guidance for 2024E is again for mid-single-digit growth. (Note that all organic figures are at constant currency, so are not flattered by sterling’s weakness through the period.)

Steam’s decent organic growth is attributed to its unique business model. Spirax prides itself on direct relationships with its customers. It has 1,300 expert sales and service engineers who are specialised by sector. They add value with solutions for all the customer’s steam-related problems. This includes “self-generated sales” where Spirax’s engineers identify opportunities for process and efficiency improvements by walking the customers’ sites.

Overall, 74% of Spirax’s steam sales are direct, with just 26% via distributors and resellers. This is a higher proportion than Spirax’s competitors.

All of the above gives Spirax’s steam business significant pricing power and favourable margins and returns. My chart below shows that the Steam segment margin has trended up over time to reach 25%. The 2017 purchase of fierce German rival Gestra was perhaps helpful in reducing competitive intensity in Europe.

For interest, I’ve also included a chart of Spirax’s sales and profit margin in Korea, which is a success story and the group’s second-biggest Asian business after China.

The business mix in Korea leans towards Oil & Gas and larger orders in conjunction with the country’s strong global EPC contractors. Given the years of weak energy capex, it’s perhaps not surprising that Spirax’s sales in Korea peaked in 2014 and have flatlined since then. Profitability on the other hand has improved.

Spirax has a 17% estimated global market share in steam. Two of its key competitors are outlined below. Another ten are named by Spirax in their presentations. None of the pureplay steam competitors are publicly listed, making it hard to track whether Spirax is outgrowing the peer group and gaining share over time.

Armstrong International is the strongest peer. Based in Michigan, it is a fifth-generation family-owned firm with 3,000 employees. Armstrong is much stronger than Spirax in Oil & Gas markets.

TLV is a globally active competitor based in Hyogo, Japan. Also privately held, with 500 employees. An entertaining testimony from one of TLV’s distributors in the north west of England illustrates how Spirax’s direct sales approach will naturally put distributors’ noses out of joint.

Watson-Marlow and bioprocessing

Even higher quality than the Steam business, Watson-Marlow and the associated bioprocessing segment is undoubtedly the best part of Spirax.

In 1958, Watson-Marlow was the first company in the world to commercialise a peristaltic pump. This is a unique type of pump that moves a liquid through a tube by squeezing it from the outside, similar to the action of milking a cow. The huge advantage of this design is that no part of the pump comes into contact with the fluid. Peristaltic pumps are therefore ideal for both sterile use cases (such as food or pharma, where the pump must not touch the fluid) as well as harsh use cases (such as mining slurries, where abrasive fluids must not touch the pump).

Spirax bought Watson-Marlow in 1990 as a tiddler for £15m. It then compounded sales at a 9-10% organic growth rate for over three decades. Combined with some judicious bolt-on acquisitions, it reached 30% of group sales and 40% of profits in 2022, before falling back in 2023 on bioprocessing destocking.

My chart below gives a good sense of the violent acceleration in the Watson-Marlow segment from 2016 on. The very high >30% margins prior to 2023 are also shown.

The brands and acquisitions in the segment are shown below. Biopure and Asepco particularly boosted the biopharm exposure. Biopure grew from £4m sales in 2013 to £38m in 2022.

Biopharm has been the key driver of Watson-Marlow’s accelerated growth. Sales to pharmaceutical and biotechnology customers increased from 33% of the total in 2013 to around 60% of the far bigger total in 2022, before falling back to 50% in 2023.

Spirax makes not just pumps but also the tubing and connectors that fit alongside them. In bioprocessing, these single-use fluid management products are highly attractive, especially due to the stickiness of getting specified into a production protocol for a drug. Spirax claims it is “Unique in the market to manufacture peristaltic pump and tubing solutions”.

The leaders in the broader Fluid Management category within bioprocessing are Sartorius, Thermo Fisher, Merck Millipore, Danaher, Avantor and Repligen – top quality names that deliver high growth and margins, and command high multiples. These companies are OEM customers of Spirax, supplying systems that include peristaltic pumps. They are also potential competitors.

Spirax defines its addressable market narrowly as peristaltic pumps and associated tubing and connectors – and it considers itself to have a 20% market share. Avantor (probably the lowest quality of the above names) is the closest direct competitor to Watson-Marlow, thanks to its $2.9bn acquisition of peristaltic pump maker Masterflex in November 2021. Avantor overpaid badly for Masterflex. They expected $300m of sales in 2022, meaning they were planning to pay 9.7x forward sales. In the event Masterflex disappointed with just $227m of sales in 2022, meaning Avantor actually paid an astounding 12x forward sales.

A new competitive threat comes from Ingersoll Rand (IR). After the 2020 merger with Gardner Denver, IR acquired the Swedish Oina and the French Albin peristaltic pump makers. In Nov’21 IR announced the in-house development of a new range of ETL (extended tube lifetime) peristaltic pumps, targeted specifically at the bioprocessing market. Most recently, a month ago IR acquired life sciences company ILC Dover for $2.3bn. Their stated rationale was as follows:

[U]sing our peristaltic pump technology, combined with the newly launched ILC Dover tubing technology to deliver liquids to single-use devices also made by ILC Dover is just one simple example of how we can help control that entire ecosystem. [Source: Ingersoll Rand ILC Dover acquisition call, Mar’25 2024]

This targets Spirax’s positioning head-on. Ingersoll Rand’s success is not assured, and Watson-Marlow remains the leading brand in peristaltic pumps with longest-established reputation for quality and reliability. Nonetheless, a sustained new competitive push from such a large and well-resourced company must be unwelcome.

Spirax Sarco sell-side analysts that have published updates since Ingersoll Rand’s acquisition have made no mention of it. It is unclear to what extent buyside participants are aware of the potential new threat.

In the immediate future, the other concern for the Watson-Marlow business is whether 2024 guidance may be over-optimistic. Spirax has guided for the segment to see a high-single-digit organic sales recovery, accompanied by a strong margin improvement. This is more aggressive than guidance from the bellwether peers mentioned above, which implies further downside risk to Spirax estimates.

Electric Thermal Solutions

Starting in 2017, Spirax built a totally new business area of electric heating solutions from a number of acquisitions.

While there is some adjacency to the steam business area, in practice the two markets are separate. Spirax is operating ETS as a distinct segment with an entirely separate salesforce.

Spirax intends to improve the mediocre business it acquired by instituting Spirax’s business model of direct selling and value-added solutions, backed by investment in new product development. It hopes in this way to lift organic growth and margins from the pedestrian levels seen so far. The jury is still out on their chances of success.

In July 2017 Spirax bought Chromalox, based in Pittsburgh, for $415m from its third private equity owner. Once part of Emerson, it was sold to PE in 2003, 2011 and 2013 before being sold to Spirax.

Chromalox has turned out to be a dog of an acquisition. An 18.4% margin in 2016 fell to 13% in 2019. The business had been starved of investment. Its French business in particular was loss-making for five years before Spirax finally took a £15m charge to shut it down in 2022.

Spirax doubled down on its Electric segment with the May 2019 purchase of Thermocoax of France for €156m. Thermocoax makes mineral insulated cable, comprising conductor wires insulated by magnesium oxide, all enclosed within a tubular metal sheath. This is used in semiconductor production equipment as a key end market, including ALD.

Spirax appointed Thermocoax’s CEO, Dominique Mallet, to lead the combined Electric business, given that Chromalox had a vacuum of competent management talent. However the appointment did not work out: Mr Mallet failed to relocate from France to the US as planned. Instead, in 2021 Armando Pazos took charge of the Electric segment. He had joined Spirax in 2020 as an outsider, with a background in Ingersoll Rand / Trane.

In 2022 Spirax spent €201m / £177m on Vulcanic of France and $357m / £296m on Durex of Chicago to further bolster the Electric segment. Vulcanic sits alongside Chromalox in electric process heating, and was itself a PE-led roll-up of ten smaller acquisitions. Durex complements Thermocoax in providing ultra-critical heating for semiconductor applications.

In 2023 the Electric segment reached 22% of total sales. Its performance has been objectively weak in both sales and margin terms. My charts below show ETS has lagged STS by 450bp in organic growth and by 950bp in margins in the five years since it was reported as a separate segment.

Spirax is continuing to invest in the Electric business, most recently via a $58m capex investment in Chromalox’s Ogden, Utah factory. The aim is to sell a range of Medium Voltage heating solutions that could allow industrial customers to switch away from fossil fuels in high-energy categories previously not served by electric solutions.

Guidance for 2024E for ETS is high-single-digit organic growth thanks to an expected recovery in semiconductor, and modest margin progress. “Onboarding costs” for Vulcanic and Durex are a source of concern for analysts on the earnings call. It seems that when businesses join the Spirax group, their cost of doing business rises as areas like health and safety and HR are levelled up to group standards. Whether or not these additional expenses are justified and repaid in the longer term is unclear.

The closest listed peers to Electric Thermal Systems are nVent Electric and Thermon in the US.

nVent is the $13bn market cap electrical spinoff from Pentair. It has performed strongly since spin, led by its Enclosures and Electrical & Fastening Solutions divisions. Tellingly, the comparable Thermal Management division is nVent’s weakest business, and one that it would probably like to dispose of given its unattractive profile.

Thermon is a $1bn small cap with a mediocre long-term track record. It is a direct comp to Chromalox.

Both nVent and Thermon have tended to trade at mid teens P/E multiples, reflecting their moderate quality characteristics. Each of them have recently re-rated into the early 20s after seeing positive forecast momentum. This appears to be outperformance relative to Spirax’s difficulties in its Electric segment.

Financials, estimates and valuation

Spirax enjoys a strong double digit return on invested capital. This has fallen to the mid teens from the previous superb level in the mid twenties, after the recent spate of large and expensive acquisitions with so far disappointing results.

The company has a long track record of investing generously in capex to support organic growth, as the capex to sales chart below demonstrates. Spirax is happy to buy capital-constrained or under-invested acquisitions and then to build new facilities for them.

Growth has been entirely self-funded, with a flat to falling share count over the long term. The balance sheet position swung from net cash in 2016 to 1.7x net debt in 2023, as the spate of larger acquisitions ran ahead of free cash generation net of dividends in the period.

Quality of earnings is generally high. In the most recent years there have been more one-off items, for example related to restructuring costs, acquisition expenses and impairments to enterprise resource planning software. Prior to any investment, I would want to take a closer look at whether these items are truly one-off in nature, or whether they should be added back to better reflect underlying cash earnings.

Given that I don’t currently intend to invest in Spirax, the estimates and valuation shown below are for reference only. I reflect numbers slightly below consensus, given my view as expressed above that there are downside risks to guidance. Visibility is relatively low into the timing of recovery in bioprocessing and semiconductor end markets. Guidance assumes a weaker first half and then a second half recovery.