USS is Japan’s dominant car auction operator. This is a high quality business, with an entrenched position, 17% ROIC and excellent free cash generation. The valuation, at 18x P/E and >5% FCF yield, looks reasonable.

The key drawback is a lack of visibility on long-term growth, beyond a low to mid single digit rate. That keeps me on the side-lines for now: I don’t currently own the stock.

Nonetheless, I regard USS as a safe place to hide, and it could play a useful defensive role within a portfolio.

Feedback is welcome. What is the right price to pay for a stock that ticks all the boxes except for growth?

Intro to USS

USS was founded in 1980, and listed in 1999. It operates from nineteen locations across Japan, up from just nine in 2000. USS has made use of M&A and greenfield expansions to increase its market share steadily, from 21% in FY00 to 40% today. USS has an ambition to grow its share to 50%.

Capital allocation is not bad. USS pursues a total payout ratio of at least 80%, including a 55% dividend payout ratio and meaningful share buybacks. USS is a dividend aristocrat that has increased its dividend per share every year for 25 years since listing.

Diversifications in used car purchasing, industrial recycling and car loans are unlikely to add value, but are modest in size and fairly harmless. I provide further details in the annex.

Used car auction industry

The car auction industry has attractive characteristics, broadly comparable to stock exchanges.

Auctions are strictly B2B only. The members are car dealers and agents who depend completely on USS and its peers to sell and buy used cars. Dealers and others have tried to disintermediate the auction houses, but none has succeeded.

The auction fees charged are small compared to the value provided. The nature of competition is not fee related. The speed and liquidity provided are far more important to customers.

Auction fees do not vary with selling prices, but only with transaction volumes. Historically, volumes in Japan’s used car market have proved fairly stable through economic ups and downs, making USS a surprisingly resilient business.

Importantly, running auctions is a fairly capital-light business, in contrast to used car dealers. At no time do auction operators need to take the millions of vehicles sold onto their own balance sheet.

Japan car market context

79 million cars are owned in Japan, a number that has increased gradually in the last 25 years. See first chart below.

The number of car registrations per year has declined gradually. Around five million new cars are sold per year in Japan, and there are over six million registrations of used cars.

Buying a used car is traditionally unpopular in Japan, a country obsessed by hygiene and newness. (See also the unpopularity of used houses, discussed in my Katitas note.) Acceptance of used vehicles is growing among younger people, however.

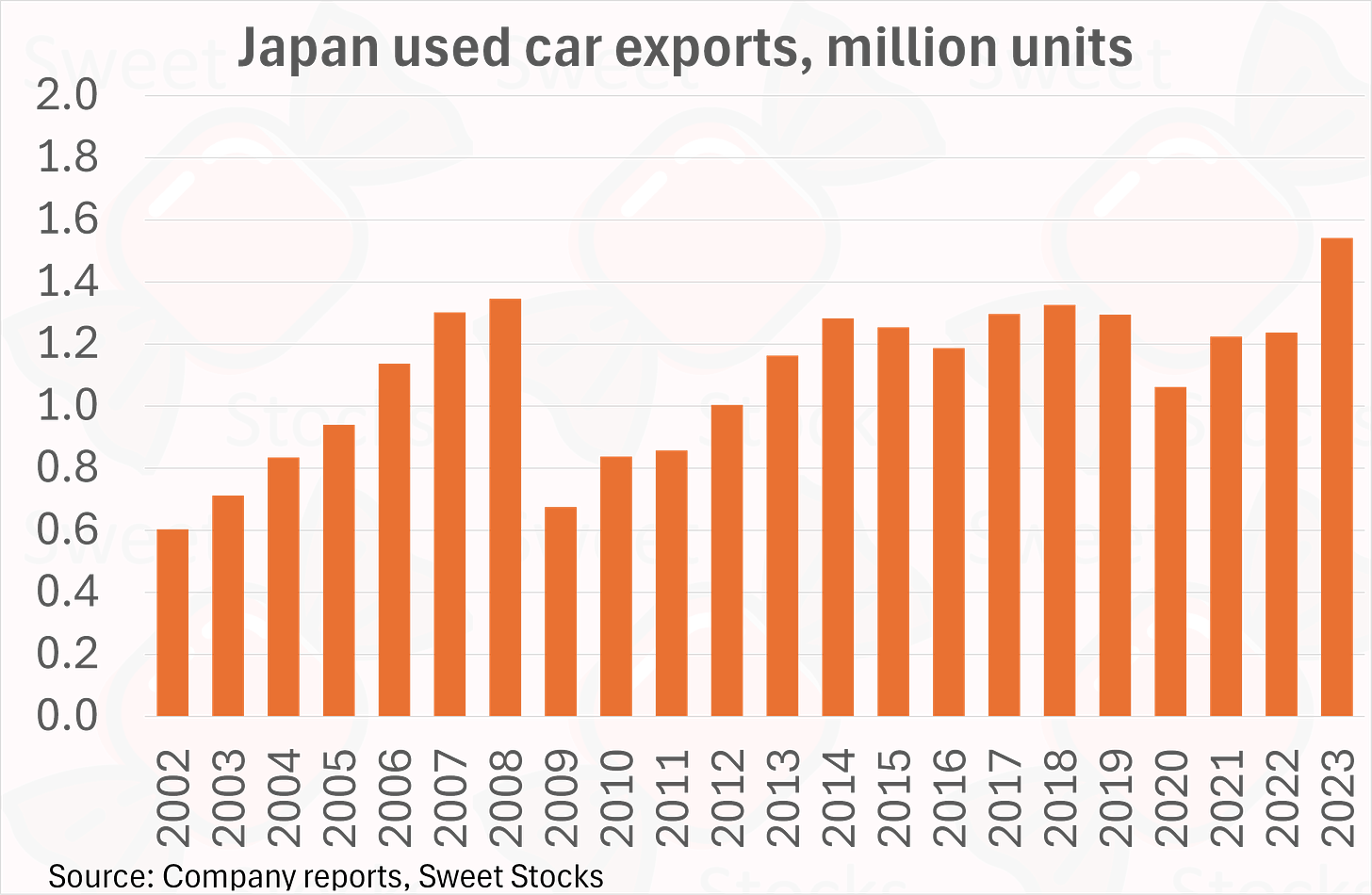

Fortunately, Japan’s used cars are coveted by overseas buyers. New Zealand, Russia, the UAE, Southeast Asia and Africa are all keen. The chart below shows that used car exports reached a record in 2023, further buoyed by the weak yen. Virtually all used cars destined for export would first be sold at auction.

The total number of cars sent to auction each year fell in the financial crisis, and has been steady since then. See my chart below. Auction operators include independent companies such as USS, and also OEM-affiliated players such as TAA (Toyota Auto Auctions), and auction sites affiliated to the Japan Used Car Dealers Association.

USS is the dominant #1 player, with 40% market share. This is three times the share of the #2 player, TAA (Toyota). All remaining players have single-digit market shares, most operating just a single site each. See my chart below.

USS’s auction business

USS was founded in 1980, and listed in 1999. It operates from nineteen locations across Japan, up from just nine in 2000.

USS’s modern auction sites allow for both physical and virtual bidding. Auctions take place weekly, with 49 auctions per site each year.

All consigned vehicles must be physically delivered to site by the day before the auction. A crucial part of the service is an inspection and condition rating provided by USS for each car.

On the day, the cars can also be scrutinised by potential bidders in person. Equally, USS provides full details of the cars to remote bidders.

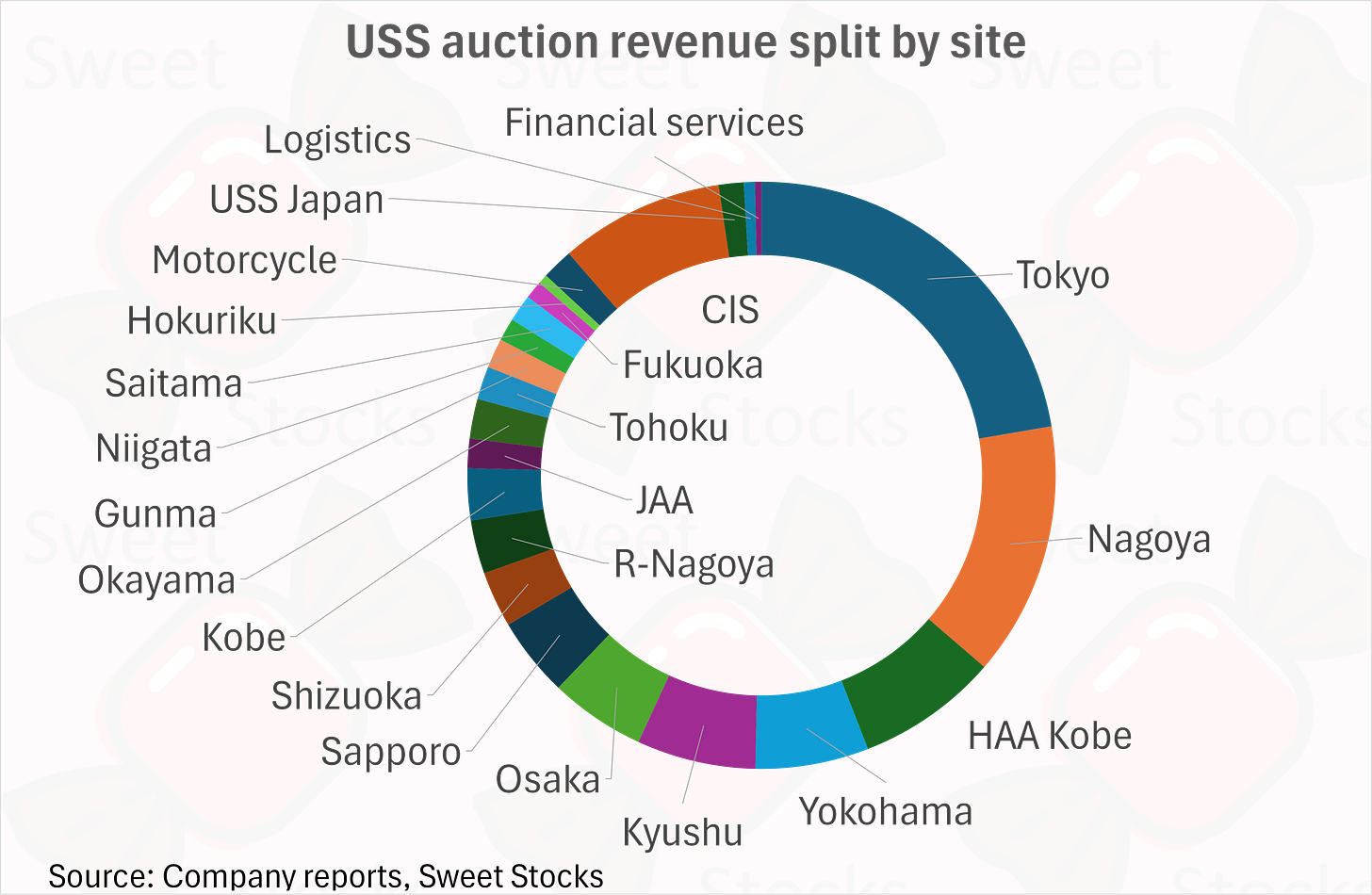

USS has two mega-sites, in Tokyo and Nagoya (illustrated above), that contribute 36% of total auction revenue between them. Other revenue is well spread across the sixteen smaller auction sites and the central revenue lines – see my chart below. (CIS refers to the internet-based information service.)

There are three main fee types that contribute to USS’s revenue.

· The consignment fee, around Y5,500, is paid by the seller for each car at the auction, regardless of whether it sells. (On average, around 65% of cars are sold at any given auction.)

· The contract completion fee, around Y9,000, is paid by the seller in case of a successful sale.

· The success fee, around Y13,000, is paid by the winning bidder.

The total average fees per successful sale are Y28k, or just 2.5% of the Y1.1m average price per vehicle sold by USS.

This low take rate is a crucial point. In more aggressive hands, USS would doubtless have significant scope for price hikes. Manheim, the leading US auction operator, generates revenue of $2.6bn on transaction value of “nearly $50bn”, suggesting a total take rate of over 5%.

USS’s conservative management are highly unlikely to double their fees overnight. Yet it is at least reassuring for shareholders to know that the value being provided to customers far exceeds the value being captured.

(It is important to note that USS’s Y1.1m average price point is nearly double the average for other auction operators of Y600k. This shows that USS’s position for the most valuable, newer vehicles is even more dominant than is reflected by its overall market share.)

My chart below shows the change in average fees over time. Whether by explicit price hikes or by mix effects, USS has already demonstrated more pricing power than most Japanese businesses during the deflationary decades, with a positive CAGR of +1.2%.

The market share driven volume gains and the increases in average fees have combined to drive respectable revenue growth for USS’s auction business.

My chart below shows a CAGR of 6.4% sustained over 25 years. The CAGR for the most recent ten years is 4.2%, which is still not bad for what should be a mature business.

USS has enjoyed positive operational gearing over time. The auction business had a segment margin of 41% in FY00, which expanded to 63% in FY24. See my chart below.

Resilience of USS auction business

USS has proved to be a resilient business over time. One possible threat would be disintermediation. Could cars in Japan ever be sold and bought without the need for an auction house?

Direct consumer-to-consumer sales are a hypothetical alternative. They used to be common in markets such as the UK and the US, facilitated by classified ads. But this segment is now in decline everywhere. In Japan it plays virtually no role.

More realistically, vertically integrated firms could undertake buying, preparation and selling of used cars without the need for auctions. In Japan, Nextage (3186.T) and Idom (7599.T) are two of the biggest used car dealer chains. Both have recently attempted to emphasise a vertically integrated business model, buying and selling vehicles through their retail networks to capture the biggest possible gross profit per unit. But Nextage and Idom remain big auction customers, both for sourcing vehicles and for disposal of unsuitable or slow-moving stock.

Two large auction peers internationally are Manheim, the biggest US player, and BCA, the UK #1. Both are private companies, though BCA was listed until 2019.

In my view, scaled auctions play a crucial role in enabling efficient price discovery for the used car industry. I expect USS to sustain its strong competitive position in the coming decades.

Financials

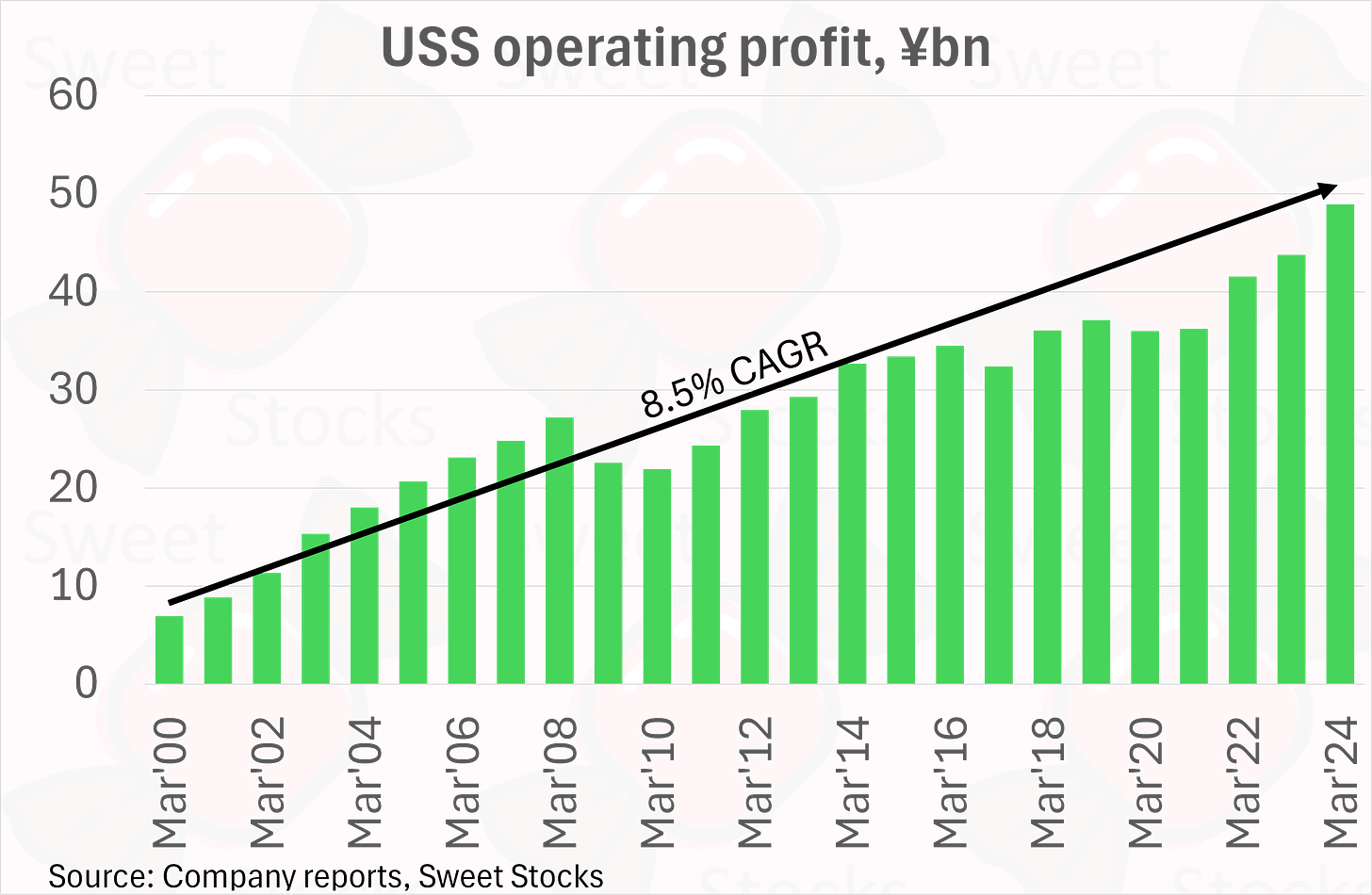

USS has built a strong track record of profitable growth. Group operating profit has grown at an 8.5% CAGR since 2000, as shown in my chart below. Importantly, the drawdowns in the financial crisis and during the Covid recession were modest, certainly compared to other automotive businesses.

My next chart shows cash from operations, capex and free cash flow. In the decade after its September 1999 IPO, USS invested heavily in building out its site network and its IT systems. In the most recent decade, that investment has borne fruit, with free cash flow inflecting up to a huge Y45bn in the year to March 2024. In my view, the market has not fully appreciated USS’s prodigious cash generation capabilities.

As part of its medium term plan, USS targets another Y120bn of cash from operations in the coming three years to March 2027 – see slide below. This would be flat against the last three years, which looks too conservative. Even with an ambitious Y20bn capex plan to expand key auction sites, this implies free cash flow of Y34bn per annum, for a >5% free cash flow yield.

As mentioned earlier, USS enjoys an efficient business model that does not require much working capital. As such, USS earns an excellent 17% return on invested capital, far above its WACC. ROIC has been >10% every year since IPO.

My chart below shows this actual ROIC, as well as the potentially even higher ROIC that would theoretically result if USS stopped hoarding significant net cash on its balance sheet.

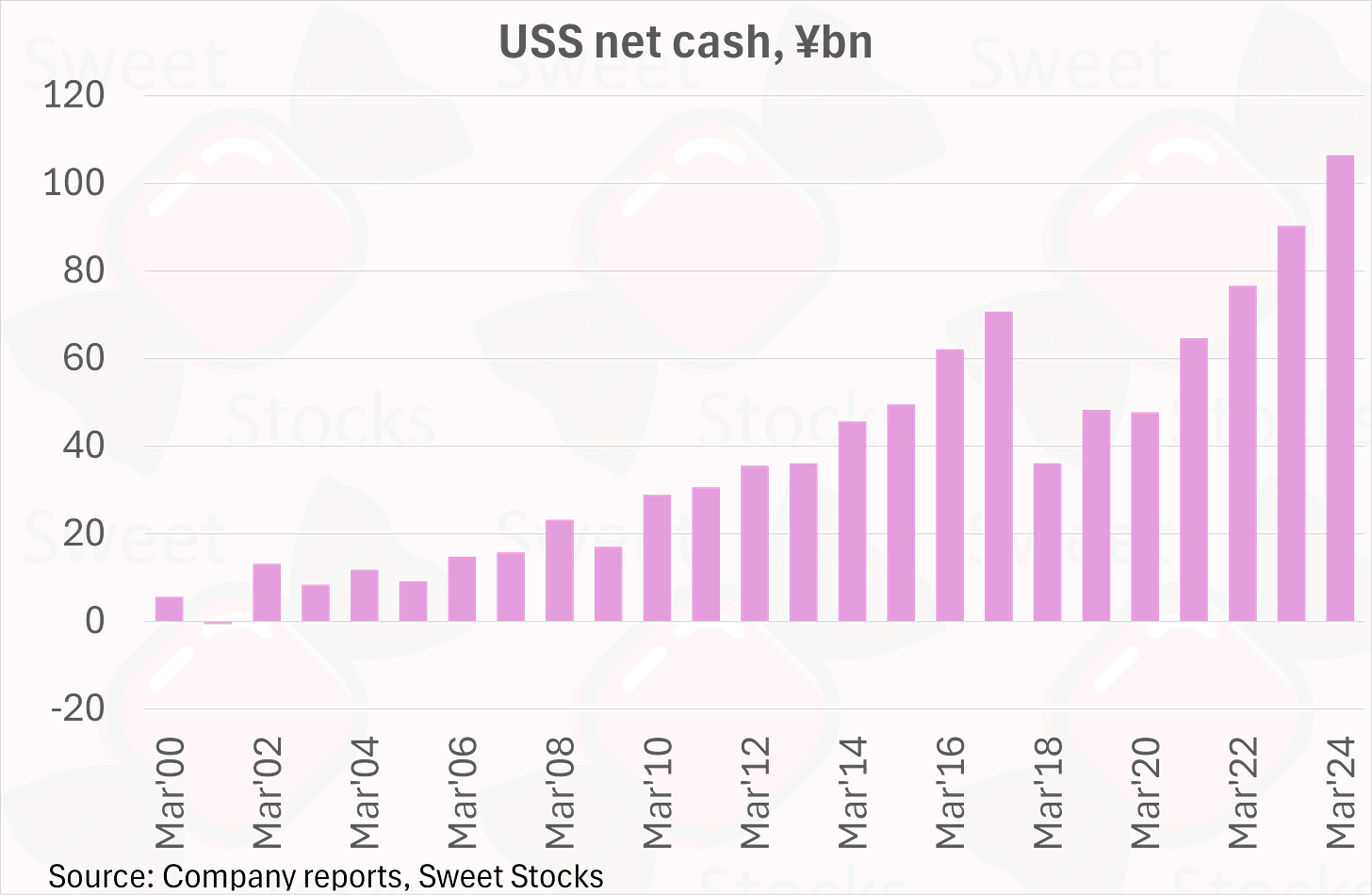

The build-up of net cash is shown below. It has reached Y106bn, or 16% of market cap. Nothing is currently in the price for the optionality this provides. If USS deploy it on either value-creating M&A (as with the Y51bn purchase of JAA / HAA in FY18), or on an exceptional share buyback, then the stock would likely respond positively.

USS’s dividends and buybacks are already decent, with a targeted 80% total payout ratio. The chart below shows the encouraging trend. However, there is clearly room for improvement, given the steady build-up of net cash on balance sheet.

Estimates and valuation

USS has a resilient, profitable and cash-generative business. Growth is the obvious concern, given the likely long-term decline of the Japanese population and the overall used car market size.

As reviewed above, USS has delivered >4% revenue growth in the last ten years, including the benefit of the major M&A deal in FY18.

I forecast similar revenue growth in the next three years, driven largely by price, with slightly better EPS growth thanks to some margin expansion and the benefit of buybacks.

It is the lack of a clear long-term growth path beyond low to mid single digits that keeps me on the side-lines. USS targets 50% market share, which would allow for stronger growth, but I lack full conviction in their ability to deliver this.

My estimates are shown below.

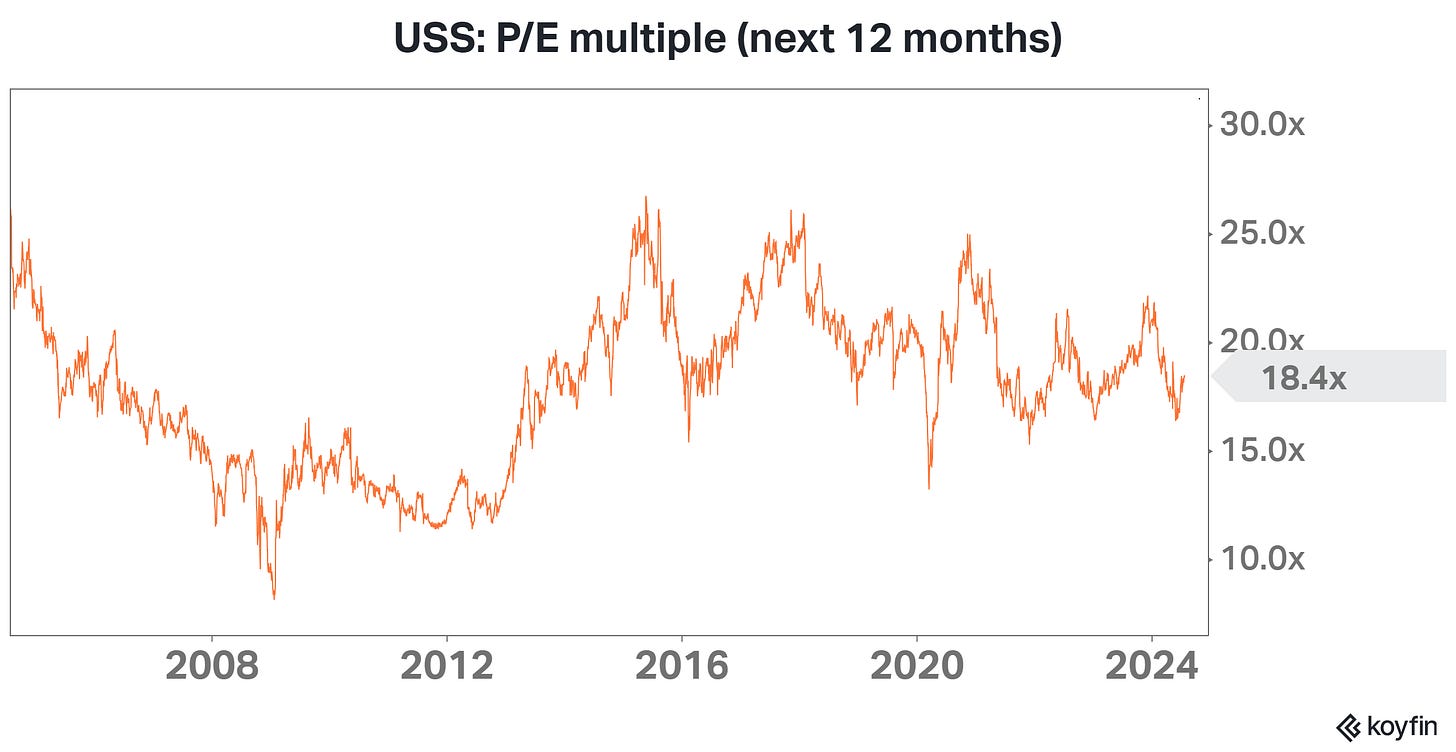

As my chart below shows, USS currently trades at the bottom of the range of the last ten years. This may reflect a view that the strong result of FY24 and the favourable export demand conditions set up a high base. Or it may simply reflect apathy towards a dull, quality midcap at a time when the action is elsewhere.

Annex: USS’s non auction businesses

The auction segment contributes 77% of revenue and 97% of operating profit. The other, far less profitable businesses are Used Vehicle Sales / Purchases and Recycling. They are not material to the investment case.

Used Vehicle Sales / Purchases is 12% of sales and 1% of profits. In this business, USS operates a chain of 138 Rabbit car purchasing shops. (Thankfully most are franchised, with just 15 directly operated outlets.) The idea is to source used car supply which can be sold at USS’s auctions. However, Rabbit is a subscale operator compared to the specialists in this category, IDOM’s Gulliver brand and Nextage.

The segment is consistently profitable but at a low level. USS seems to have recognised Rabbit is not a winner, because it has allowed the number of stores to gradually dwindle, and is not shovelling extra capital into the business.

The Recycling segment is 11% of sales and 2% of profits. It consists of two businesses.

· ARBIZ is a worthy attempt to profit from the circular economy, scrapping cars to recycle the steel content. Profitability depends on the ferrous scrap price.

· Since 2020, USS expanded into SMART for industrial plant recycling. This slightly alarming business takes on large-scale plant and equipment dismantling projects.

Since April 2023, USS launched a new auto loan business that targets young people, freelancers, foreigners and other groups who don’t qualify for conventional auto loans. The trick is to install a device that can safely immobilise the engine when payments are delayed. USS has partnered with buzzy Japanese fintech start-up Global Mobility Service to offer this technology.

They recruited 650 affiliated stores, and extended Y5.7bn in credit to 4,000 borrowers in the first year.

any thoughts on Aucnet or Autoserver?

Great writeup