Watches of Switzerland – time for the US

(WOSG.LN, $1.2bn market cap, $2.6m ADVT, 96% free float)

I spoke to WOSG’s management in preparing this report. All opinions and estimates are solely my own responsibility. Feedback is welcome as always.

Watches of Switzerland Group (WOSG) is a leading UK and US Rolex retailer (c.55% of revenue) that also sells other watch brands and jewellery.

In an industry that prizes longevity and stability, WOSG is proud of its hundred-year relationship with Rolex.

Yet paradoxically, both WOSG and Rolex itself have changed significantly in the last six years. That makes the future harder to predict, as is evident from the 43% cumulative downgrades to FY25E EPS since consensus first struck their estimates back in 2022.

WOSG has been punished heavily for this uncertainty, and trades on a current P/E of just 9.4x.

In this report I first provide an overview of WOSG’s history, management, and the shape and size of the group as it stands today.

A key question is whether WOSG’s aggressive capital allocation, funnelling all cash flow back into expansionary capex and acquisitions, is the right approach to maximise shareholder value. I find their US development, the biggest use of capital, is clearly adding value, while some UK investment looks marginal at best.

I provide a proprietary peer review of eight other Rolex retailers in the UK and overseas. The peers are consistently highly profitable, underscoring just how attractive a Rolex dealership is. They provide reassuring evidence that WOSG has not yet come near to over-earning in margin terms.

I then engage head-on with the various headwinds, risks and fears that weigh on the stock. After my warts-and-all examination, I give WOSG a fairly clean bill of health, and conclude that the stock is most likely too cheap.

The relevant disclosure is that I have owned WOSG since 2023, and as such I have been early (a.k.a. wrong) on the stock. I added to my position after January’s profit warning; it sits just outside my top ten in size. I leave it to the reader to judge whether my objectivity has been impaired by the holding.

History

The key constituent parts of the group have long histories.

· Goldsmiths became the first authorised Rolex retailer in the UK in 1919, and by the start of the current century it was the biggest.

· Mappin & Webb has an illustrious history dating back to 1775.

· Watches of Switzerland itself has been selling luxury watches in the UK since 1924: at first known as G&M Lane & Co, it adopted the Watches of Switzerland brand name in 1947.

· Mayors has been selling watches and jewellery in Florida since 1937.

In 2004-06, the mercurial Icelandic retail investor Baugur acquired the Goldsmiths, Watches of Switzerland and Mappin & Webb chains and amalgamated them into a single corporate group. They paid £110m for Goldsmiths and £21m for Mappin & Webb (which included Watches of Switzerland). In 2007, the combined group was renamed as Aurum.

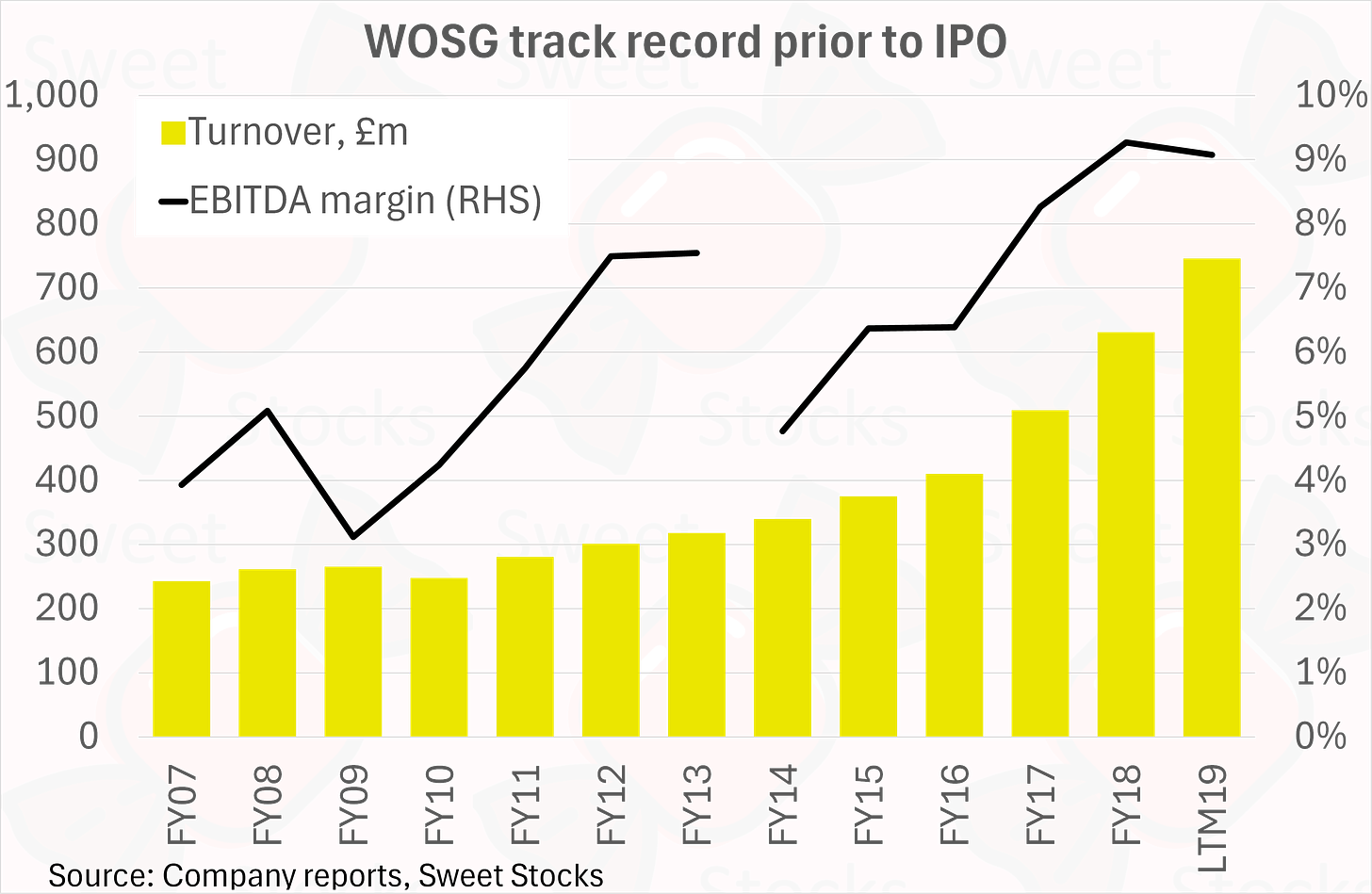

In operational terms, Aurum developed well from inception, with a 4.6% revenue CAGR and a 16.6% EBITDA CAGR from Feb’07 to Feb’13. See chart below.

From 2008, the global financial crisis situation developed not necessarily to Iceland’s advantage. Control of Aurum passed to the nationalised Landsbanki.

In March 2013, Apollo acquired the group, with a plan to sweat the assets in typical PE fashion. They brought in Brian Duffy as CEO. He saw an opportunity to elevate and transform the business.

The business Apollo bought in 2013 was by no means a pure or genuine luxury business. Rather, the Rolex and other luxury watch franchises were intermingled with affordable watches and jewellery in an ordinary high street setting. The Goldsmiths brand and stores were tired.

Duffy made key early investments in refurbishing the 155 Oxford Street and Knightsbridge stores. He raised the bar in the UK market: to represent top brands the store and staff should be of top quality. Brands and landlords both loved the results, which kickstarted a flywheel of investment opportunities.

The result was an acceleration of growth as well as a new high for margins. My chart below shows the track record from FY14 to LTM19 used in the IPO prospectus, as well as the history under Icelandic ownership for context.

Most significantly, Rolex were pleased with WOSG’s elevation of the brand in the UK. As a result, they blessed the group’s three-pronged entry into the US market from 2017. This is Duffy’s crowning achievement. It is evidence of capable capital allocation that has generated significant value for shareholders, as I detail further below.

Key management

Brian Duffy came to the group in 2014 from Ralph Lauren. He has transformed WOSG beyond recognition with the elevation strategy and the push into the US. The strong relationships of trust he has developed with his Rolex counterparts in Geneva have been instrumental. Duffy celebrated his 70th birthday this summer, making him one of the older FTSE 350 CEOs. While his commitment to the business is currently unquestioned, investors will be mindful of the eventual need for a smooth succession. Duffy owns 3.2% of WOSG.

Anders Romberg has been CFO since 2014. (There was a brief interruption from January 2022, when he retired from the group for personal reasons. He was able to return to the CFO role in May 2023.) Romberg had previously worked with Duffy at Ralph Lauren, where he held CFO and COO roles for the EMEA and Asia Pacific regions. Romberg owns 0.5% of the company, worth nearly £5m.

Craig Bolton is President, UK. He is a survivor from Aurum since March 2004. This demonstrates commendable longevity.

David Hurley is President, North America and also Deputy CEO. He has served at Aurum / WOSG since Nov’15. He previously spent ten years at Ralph Lauren in both Europe and the US, where he will have worked alongside Duffy. His success in developing the US business earnt him the Deputy CEO title in April 2022. Investors will infer that he is front and centre of the succession plan when the time comes.

Hurley and Bolton have both developed direct relationships with key Rolex personnel in Geneva, as a necessary part of the succession planning process.

Eric Macaire is Executive Director for Global Buying and Merchandising. He joined the group in January 2023, with a background in purchasing watches and jewellery for LVMH’s DFS Group.

Profile of the group’s operations

WOSG today has 214 stores in the UK and US. I identified a total of 63 Rolex doors, leaving an estimated 151 stores not anchored by Rolex. My table below provides details.

Aside from a tiny number of Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet franchises, the non-Rolex stores mainly focus on the so-called strategic partner brands of TAG Heuer, Omega, Breitling, Tudor and Cartier, with far lower ASPs on average compared to Rolex.

(Such is WOSG’s reticence regarding all matters Rolex that it does not provide a store breakdown by brand or agency in its written materials.)

By region, the revenue split in FY24 was 55% UK & Europe, 45% US. My chart below shows that the US has been contributing almost all the growth, while the UK has been flat or shrinking for two years or more by now.

WOSG’s revenue split by category is 87% luxury watches (defined as RRP >£1,000), 7% luxury jewellery (RRP >£500), and 6% services and other products. The dominance of watches has risen since IPO, when the split was 82% watches and 10% jewellery. Jewellery is a more seasonal and volatile category, with a bigger Christmas trade than watches.

WOSG provides data on average selling prices for both watches and jewellery in each region. At the average, luxury watches sell for £6,689 in the UK and $13,246 in the US: see chart below.

These average prices are in fact Frankenstein statistics. They include Rolex watches sold at typical prices of perhaps £8-30k alongside the likes of TAG Heuer watches at £2-4k.

The mix of revenue by brand is crucial information for investors. Yet it is sensitive enough that WOSG does not provide it on a regular basis. In the May 2019 IPO prospectus, they did tell investors that Rolex watches represented 45% of total revenue in FY18, rising to 51% in 9M’19. The then-tiny US business had an even higher proportion of Rolex sales.

The next bulletin we got was in December 2021, when WOSG disclosed the exhibit below. This shows that the mix of Supply Constrained Brands (defined as Rolex plus the tiny Patek Philippe and AP sales) was 61% in H1’20, 69% in H1’21 and 59% in H1’22.

The story behind the high 69% figure in H1’21 is that Covid lockdown store closures heavily impacted sales of most other brands, but the Supply Constrained sales held up strongly thanks to the ability to take 100% deposits from customers on wait lists when their watches arrived in store.

Guidance from the company is that the proportion of Supply Constrained Brand revenue has remained at around the 60% level ever since. Rolex would be the lion’s share at c.55%.

As mentioned, WOSG’s store design is a key point of differentiation. They favour large and luxurious stores that are welcoming and non-intimidating, with full-length windows. The stores provide a modern environment for luxury watch buyers, a large proportion of whom are under 40. (75% are men.)

Economics

The economic model is straightforward. WOSG earns a fixed percentage margin on each brand. For Rolex this is thought to be around 33%, while other brands (with lower ASPs and weaker bargaining positions) allow appreciably higher percentage retailer margins. Brands exercise strict control over retail prices, and discounting should be minimal to non-existent.

Note that Rolex can and does reduce the permitted margin from time to time. Most recently, in May 2022 Rolex cut the US margin to bring it into line with the UK level. See below for how the CEO Duffy described this on the WOSG FY22 earnings call.

“So, on Rolex margins. The margins that we've had in the U.S. have always been higher than we've had here in the U.K. and elsewhere in Europe, I believe. That's because U.S. stores were typically less productive. As time progresses and we get more productive and retail the brand better, we've got more productive. This was something that was anticipated in the Long Range Plan that the U.S. margin would come in line with the U.K. margin over time. And that's what's happened. So it's something that we knew was going to happen at some point. It's probably happened a little bit earlier than we would have liked. But it's coming with effect from 2022.”

WOSG’s blended net margin was 36.6% in FY24. This is a pretty stable figure, albeit it has drifted down by 130bp since FY18. See chart below.

Beneath the net margin, WOSG incurs showroom costs, staff, advertising, overheads and D&A. This results in an adjusted EBIT margin of 8.8% in FY24, which is down 190bp from the prior year peak level, but still higher by 260bp from the pre-IPO level of FY18. See chart.

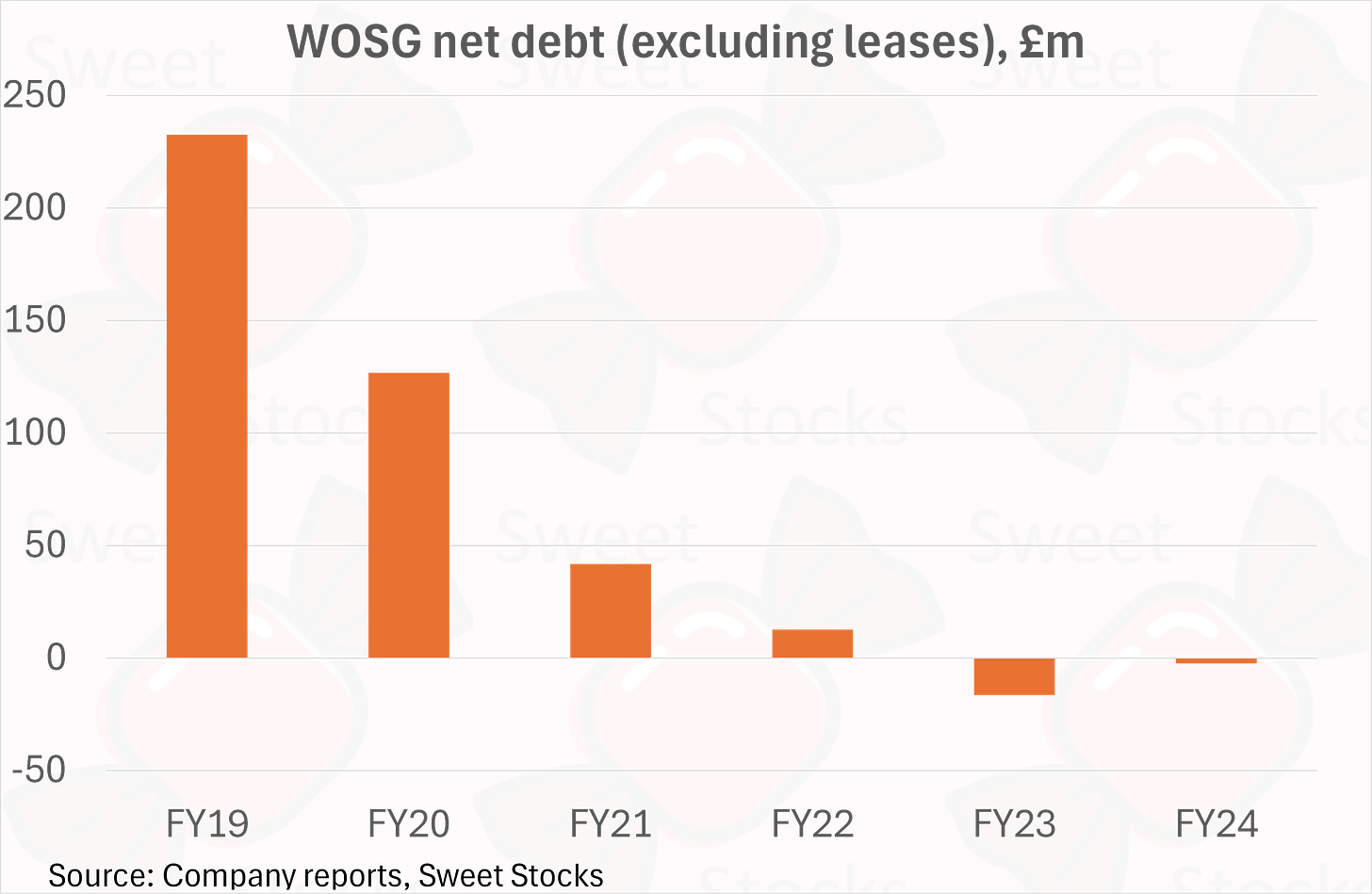

WOSG has generated £579m of cumulative cash from operations in the last six years. It has reinvested the vast majority of this, £458m, into expansionary capex for lavish refurbishments and some landmark new store developments, as well as M&A of existing stores. My chart below shows £121m of cumulative free cash flow after all spend on capex and M&A.

WOSG has chosen not to pay any dividends or buybacks given the large growth opportunity it sees. It has paid down net financial debt since IPO, with net cash at the end of FY23 and FY24 – see chart below.

(Note that after the FY24 year-end, WOSG paid $130m to acquire the Roberto Coin US distribution business, funded by a new term loan. So they have moved into modest net debt on a pro forma basis.)

The US build – a case study in strong capital allocation

As noted above, WOSG has reinvested heavily, and plans to do even more of the same in the coming years. The lion’s share of investment goes into the US. I argue that WOSG has done a superb job of its US entry and expansion – words that are rarely said of a UK-based retailer.

The US business has far higher ASPs for both luxury watches and jewellery than UK. This demonstrates that the US is a better business, as it has been anchored by Rolex and other top brands from the start, without the baggage of the lower-priced and non-luxury product that Goldsmiths has always carried in the UK.

Future prospects for the US are strong, given the penetration of luxury watch sales is less than half the UK’s level on a per capita basis.

According to my model (below), WOSG has spent a cumulative total of £310m in cash on acquiring and building the US business. I estimate that they are achieving a high teens post-tax ROIC on this investment, far above the WACC, which makes it money well invested.

Weaker capital allocation in Europe

WOSG’s investments in the UK and Europe have been weaker than the US success. In my view, the following investments were either mistaken or marginal.

· Non-Rolex stores. In the years after IPO, WOSG invested heavily in opening new monobrand stores across the UK for non-Rolex brands such as Breitling, Omega and TAG Heuer. These stores have subsequently been commented to have low productivity. £21m of store impairments were taken as an exceptional item in FY24. WOSG does not disclose which stores are impaired. It blames the interaction of IFRS-16 accounting and the sharp rise in interest rates for the impairments. Nonetheless, it is notable that no stores with Rolex have been impaired. I guess that the recently opened non-Rolex monobrand stores are over-represented among the impairments.

· From 2022, WOSG opened nine greenfield monobrand stores in continental Europe. These were with non-constrained brand partners Breitling, Omega and TAG Heuer. No new Rolex agencies were granted to WOSG in Europe, different to its initial New York entry six years ago. WOSG’s thesis for Europe was to follow up on the initial stores with favourable acquisitions anchored by Rolex in order to gain the necessary scale. But it proved impossible to find a suitable acquisition. WOSG recently announced it will exit from its nine European stores. It took an initial £9m impairment, which is an estimate pending completion of the transfer of the stores to the brand owners.

· In late 2023 WOSG acquired 15 luxury watch showrooms from Signet’s Ernest Jones. It paid £44m, which included £25m of inventories, for revenue of around £30m. The acquired stores are located in provincial towns around the UK. No Rolex agencies were included – in fact Ernest Jones lost its Rolex partnership over ten years ago. For WOSG, the deal was an opportunistic one that served to remove a competitor from the luxury watch market completely. (It is helpful to remove a rival bidder from online ad keywords, for example.) The acquisition price was modest after taking inventory into account. But it increased exposure to less desirable non-Rolex stores.

· Overall, I have reservations about the quality of non-Rolex stores. In my view these are not true luxury businesses, and are cyclically exposed to the weak UK consumer. Customers in these stores rely on subsidised interest free credit (IFC) to quite a high degree: IFC accounts for 12% of total WOSG sales, but is never applied to Rolex, meaning that the penetration of IFC on other brands must be north of 25%.

Rolex itself

Rolex is owned by a charitable foundation. An ethos of total secrecy means data is limited. What we do know is that Rolex has been extraordinarily successful, both in the hundred years since it was founded, and especially in the last ten years when it has delivered accelerated growth into heightened demand.

Morgan Stanley’s annual report on the Swiss watch market is generally accepted as the best available set of estimates on sales and market share.

Rolex has been a relentless market share gainer, and the standout success story among Swiss watch brands. See chart below: Rolex’s share is estimated to have risen from 20% in 2017 to 32% last year. Rolex has leapfrogged Swatch and Richemont into first place, and left LVMH for dust.

We have longer time series data on the volume of Rolex watches sold each year, thanks to the historic COSC certification data that was issued annually until 2015. See chart below: I was surprised that Rolex volumes did not exhibit a strong growth rate throughout the decades prior to 2015. Instead, rapid growth is a far more recent phenomenon. This makes it harder to predict what impact, if any, the far higher recent volumes might have on Rolex’s brand image and future demand in the years ahead.

Rolex’s acquisition of Bucherer

A year ago, in August 2023, Rolex dropped a bombshell by acquiring Bucherer, WOSG’s closest rival. Bucherer has large city-centre stores in the US, London, Switzerland and several other European countries.

WOSG’s >50% exposure to Rolex always posed an obvious concentration risk, at least in theory. Prior to this deal, investors could take comfort from the fact that Rolex strictly abstained from any direct retail or own stores. It was purely a wholesaler, making it as dependent on its retailer partners as vice versa.

The Bucherer acquisition destroyed this logic. Suddenly the concentration risk looked far more real. What if Rolex decides to gradually shift a greater proportion of its total retail network into Bucherer’s hands? The distribution agreements permit termination of agencies on a few months’ notice without cause.

In fact Rolex explicitly denied any such intentions. The purchase of Bucherer was said to be for succession purposes only. (Jörg Bucherer was 87 years old, had no direct descendants, and died less than three months later.) Rolex stated that “the fruitful collaboration between Rolex and the other official retailers in its sales network will remain unchanged”.

One year on, no disturbing signs have been detected. Rolex has continued to allocate watches to its retailers and agree new store plans as normal.

Personally, I am inclined to believe Rolex’s assurances. I view the hundred-year history between the two firms as having been mutually beneficial, and predictive of a further long and stable relationship ahead.

Many investors will understandably take a different view and choose to steer clear. WOSG is likely to continue to trade at a discount to reflect the concentration risk for years to come.

Some other concentration risk examples might be helpful.

· At the extreme, Nvidia and TSMC are two firms locked into a mutually beneficial supplier / customer relationship where investors on both sides are pretty comfortable with any hypothetical concentration risk. However, the balance of power and specifics of how likely a concentration risk is to crystallise are very different in each case.

· More prosaically and of closer relevance, JD Sport is a strong retailer that has c.50% dependence on Nike as its key supplier. In this case, Nike’s execution mis-steps and sales slowdown have hurt JD Sport, rather than any termination of agency.

Peer analysis: WOSG in context

Has WOSG been over-earning? What is a fair normalised EBIT margin, given the recent range of 3-11% that I showed above? We can compare the financials of other authorised Rolex retailers to get some clues.

The Hour Glass (AGS.SI, $780m market cap) is a Singapore-listed watch seller with Rolex dealerships in Singapore, Thailand, Australia and New Zealand. It has achieved a far higher profit margin than WOSG, with an average PBT margin of 19% over the last three years as sales have boomed. THG appears to have a superior cost ratio to WOSG in terms of staffing, store costs and marketing expense. A different mix could be a key factor: THG may have an even higher share of Rolex and other demand-constrained revenue (not disclosed), which comes with better economics thanks to far higher store productivity compared to more marginal brands.

Oriental Watch (0398.HK, USD201m market cap) is a Hong Kong listed Rolex retailer with Rolex dealerships across Hong Kong, Macau and the PRC. It discloses its dependence on its key supplier at a huge 89% of total purchases. Its OP margin in the last three years has averaged 11.7%, modestly higher than WOSG’s 10.0% for the same period. The challenging environment in greater China is visible in the far less buoyant revenue for Oriental Watch compared to its peers. See below.

Closer to home, WOSG’s rival Rolex retailers in the UK include many family-owned businesses with financials available via Companies House. I was surprised at how healthy these players were in terms of both growth and profitability. They are evidently not to be underestimated as competitors to WOSG, despite their smaller scale. After Rolex weeded out many weaker and underperforming retailers in the last fifteen years, perhaps the survivors tend to be of high quality and able to meet Rolex’s exacting standards.

David M Robinson has Rolex stores in Liverpool, Manchester and Canary Wharf, London. It has invested in its business and reaped the rewards, with impressive growth to pass £50m in sales. Its operating margin in the most recent two years available was slightly above WOSG’s for the same years. See chart below.

Pragnell has Rolex stores in Stratford-upon-Avon, Leicester and Mayfair. It has a nice track record of profitable growth. Its most recent margins of around 12% are higher than WOSG’s. See below.

Berry’s has stores in Leeds, Newcastle, Windsor, Nottingham, Hull and York. While they lost their Rolex AD status back in 2011, they have three Patek Philippe stores that appear to be driving strong growth and profits. Berry’s operating margin at 20% in the last couple of years is notably high. See below.

Preston’s operates Rolex stores in Leeds, Guildford, Wilmslow and Norwich, the latter a recent acquisition. Preston’s profitability of around 13% is well above WOSG’s. See below.

Laings has Rolex stores in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Southampton and Cardiff. Its growth has been strong but profitability is more muted, in the single digit range.

EP Mallory is a Rolex retailer with a single, large, well-established site in Bath. Its purely organic revenue growth and its astonishing operating profit margin of over 20% are testament to the fact that scale is not necessarily required in this line of business.

In conclusion, holding Rolex dealerships has certainly been a pleasant business for the last few years.

We can say that WOSG is not over-earning relative to its peers. If anything the reverse: many peers have exhibited far higher margins in the recent peak period on comparable growth rates.

WOSG has been investing heavily in its elevation and growth plans, both via capex and opex. This investment may have weighed on margins. In addition, WOSG in UK may have a less favourable mix of non-constrained and non-luxury revenue than the small Rolex retailer peers.

Cycle and profit warning

WOSG is down over 70% from its late 2021 peak. That is far worse than the two Asian Rolex peers – see chart below. I suspect that the relatively recent IPO, the extremely high peak multiple on peak expectations reached in 2021, over-optimistic guidance and some execution mis-steps are all to blame.

Most fundamentally, the luxury watch market overheated significantly in 2021. This has now gone into reverse.

The longer perspective is that wait lists for Rolex did not used to be a thing. Ten years ago, anyone could buy most models of Rolex with no need to wait. This is proven by the exhibit below from the WOSG prospectus, showing 87% of Rolex were sold from stock in 2014, a figure that was still 67% as recently as May 2019.

The recent Covid-and-crypto cycle of huge demand and limited supply for Rolexes led to a situation where all Rolexes were unavailable from stock. Long wait lists caused secondary market premiums to spike, which led to even further primary demand.

This situation evidently resulted in record high margins for almost all Rolex retailers, as seen in the peer charts above.

WOSG has impeccable compliance in place to ensure that its staff do not exploit Rolex scarcity inappropriately. Nonetheless, WOSG and other retailers likely benefited from some customers choosing to spend more on other items in the hope of building up “credit” to improve their chances of a coveted Rolex allocation, as they perceived it. Any such revenue will soon fall away, as secondary market premiums disappear, and many Rolex models will likely become available from stock once again. (This is already true of certain less desirable Rolex models today.)

A key WOSG mistake was in allowing the sell side and the buy side to extrapolate peak growth and margins into the future. Back in early 2022, the sell side struck FY25 estimates of £1.96bn of sales and over 12% adjusted EBIT margin. With hindsight it was never sensible to extrapolate up-and-to-the-right in this way.

Duffy’s optimistic nature may have contributed to these unrealistic expectations. (Compare the more cautious commentary provided by The Hour Glass in May 2022; the chairman wrote about their recent “crypto bro” clients, the likelihood of sharp rate hikes and the possibility of a bust in the global watch market.)

It may also be the case that WOSG’s desire for discretion or secrecy regarding brand-sensitive details impeded investor understanding. (E.g. no like-for-like sales data issued, no quantification of key mix data.)

Estimates

WOSG presented their Long Range Plan (LRP) as recently as November 2023. They promised to more than double sales and profits by FY28, including 50bp to 150bp of margin improvement vs the FY23 base. Yet just two months later, the group was forced to issue its profit warning for FY24, blamed on a surprise change in the mix of Rolex watches allocated to WOSG, as well as weak demand for jewellery and other watches in the UK in particular. The credibility of the LRP is therefore low. It now requires at least 230bp of margin recovery vs FY24.

We have a situation where UK sales contracted 6% yoy in the six months to April, despite the benefit of the Ernest Jones acquisition. The underlying organic sales fall must have been close to 10%. And yet consensus is still projecting double-digit sales growth each year for the group.

It is true that significant and high-yielding new store openings are due which provide some backing to the growth estimates. The Roberto Coin acquisition also makes an immediate contribution, along with greater efforts in luxury branded jewellery. The rollout of Rolex’s new Certified Pre-Owned scheme is the other major growth driver.

Nonetheless, I see downside risks to sell-side estimates.

My estimates, shown below, are c.10% lower than the consensus average. This reflects my expectation of further weak trading in the UK in particular. I believe the buyside is on the same page as me, and the stock will do well if my estimates are delivered.

(For clarity, neither consensus nor my estimates factor in anything for additional M&A not yet announced. WOSG does intend to make further acquisitions, preferably involving US Rolex dealers. Speculative M&A would be one reason why consensus’s FY28E estimates sit far below what WOSG’s LRP implies.)

The valuation history since IPO is shown below. The stock now trades below 10x consensus NTM P/E. Concentration risk in light of Bucherer is one key fear for investors. The downgrade cycle having (much?) further to run is the other key fear.

Conclusion

WOSG has been the subject of several recent write-ups. These include Eagle Point Capital, Compound & Fire, and Plural Investing’s interesting study of Rolex vs other brands in a multi-brand store. All three of those write-ups have capably summed up the bull case for the stock and the story that management wish to promote.

My own preferred approach in a situation with a sharp drawdown is to dig into all possible aspects of the bear case. What has been going wrong, and might it continue for longer than expected?

In WOSG’s case, I think it is easy to understand why the stock has been so weak. Existential concern has coincided with cyclical malaise, especially in the UK with its slightly too high proportion of aspirational and therefore vulnerable low-priced business. Nonetheless, from here the risk-reward looks favourable.

As stated up top, I have been a holder of WOSG for longer than I would like. I added to my position after the January profit warning, and I continue to hold.

Fantastic write-up. The problem in the industry is that certain Rolex ADS have been pushing clients to buy lower-priced watches to qualify for Rolex and Patek waitlists. This is particularly common in Singapore and Hong Kong. WOSG doesn't do this to the same extent, and I think that's why its margins remained stable throughout the 2020-2022 COVID era watch bubble.

Great write-up, as always. My understanding is that luxury watches (esp Rolex) are in decline in cache. Instead there are multiple independent brands for collectors (FP Journe-now with a somewhat tarnished reputation-, Kari Voutilainen etc etc etc, but I'm not an expert.

Alex, How do you get to meet with management? I'm a private investor, but struggle to get past the 'Investor Relations' gate. In my experience, the IR people do then not know the business very well. I invest decent sized amounts, so you'd think management would want to engage with long-term holders.