“Webjet is burning through the sky, yeah

Two hundred degrees, that’s why they call us Mister Fahrenheit

We’re travelling at the speed of light

We wanna make a supersonic investor out of you

We’re on track to deliver significant growth in FY25…”

MD John Guscic was in ebullient mood on Webjet’s earnings call a fortnight ago, treating analysts to two snippets of Queen. After a tough thirteen year journey building a valuable global business from scratch, he was arguably entitled to a moment of vindication.

Webjet is a USD2.3bn Australian travel group that just announced it is exploring a separation of its two divisions via a demerger.

This will shine a spotlight on WebBeds, its relatively unknown, highly profitable and fast-growing global B2B hotel distribution platform.

WebBeds was only founded in 2012, and is just now emerging from the Covid haze. It has the potential to become a long-dated growth stock at a reasonable price.

As a so-called bedbank, WebBeds plays a niche role in the wholesale plumbing of the global travel industry. While esoteric, the model is worth understanding, because WebBeds may be a rare travel small cap that can continue to flourish alongside the giants of Booking, Expedia and Google.

Meanwhile, the domestic B2C Webjet business is a survivor from the original Dotcom bubble in 2000. As the leading online travel agent for Australia and New Zealand, it promises to be a stable cash generator.

In this post I lay out the business models and track records of each half of the group. I benchmark the businesses to their closest peers, and consider possible competitive threats.

My estimates put the combined group on a valuation of 22x current P/E, falling to 15x in Mar’27E — cheap if they can deliver the earnings growth I expect.

After demerger, I assume the Webjet part may trade at c.13x, while WebBeds could trade on c.26x.

I am a buyer of Webjet at around the current price. As always, feedback is welcome.

Webjet history: act one

Webjet was born in April 2000, with a backdoor IPO via a failed junior mining stock called Roper River Resources. Roper was one of 90 Australian mining companies that announced they were converting to dot coms at around the same time.

The IPO came too late in the dot com bubble to capture any excitement, and the stock was down 80% by mid 2001.

However, against all the odds, Webjet’s founder David Clarke went on to do exactly as promised. With assistance from Microsoft, he grew Webjet to become the biggest online travel agent in Australia and New Zealand. See charts below showing the handsome revenue growth and total return he delivered for early investors from 2000 until 2013.

Webjet history: act two

In 2011, David Clarke handed over the leadership of Webjet to John Guscic, who remains Managing Director today.

Unusually, Guscic had already served as a non-executive director of Webjet since January 2006, and as a board observer from 2003 to 2005. The association began when he arranged for his then-employer Travelport to make a A$1.5m investment in Webjet. This helped to pay Microsoft to build the original Webjet transactional website, using their .NET framework.

[Guscic’s biography often mis-states the date he first became a director as 2003, a minor error which has been present since the first official announcement of his appointment in 2010. The distinction between board observer and director is admittedly a pedantic one. At the time of writing, Webjet’s website has the correct 2006 date, while WebBeds’s website has the wrong 2003 date.]

Guscic’s day job at Travelport was building up their B2B hotel bedbank business called GTA, first as managing director for Asia Pacific, and then as global COO based out of London.

In 2007, Webjet bought back the Travelport stake, but they asked Guscic to remain on the board as they valued his input.

Then in 2010, they announced him as the next MD to succeed David Clarke, who was retiring.

A year after starting at Webjet, in mid 2012 Guscic began working on a bedbank startup called Lots of Hotels, based in Dubai. This was the nucleus of the business that became WebBeds.

Why do bedbanks exist?

There are several hundred thousand hotels worldwide. Their imperative is to achieve their targeted occupancy levels, every night, at the highest possible rate. To do this, hotels want to access the widest and most diverse pools of customers possible, and they are willing to pay good commissions for help with this.

Some customers (about 45% on average) will book directly on the hotel’s own website (or by phone, fax, or by walking into reception). That’s simple and high margin, with no commission payable. Hotels love it.

Another c.40% of customers will book via a company that has a direct contract with the hotel to sell its rooms. Booking and Expedia are the biggest such firms. Regional online and offline travel agents, major tour operators and other large travel sellers are also included. The hotel will pay the intermediary an agreed commission as per their contract.

The final c.15% of customers book via firms that don’t have direct contracts with the hotel in question. This is the c.$75bn market for hotel wholesalers or bedbanks. They exist to help hotels sell more rooms to additional customer groups worldwide, beyond those that can be reached by direct contracts.

Bedbanks contract with hotels to sell their rooms on to retail travel agents, corporate travel agents, airlines, tour operators, loyalty and reward programs, as well as to online travel agents and other wholesalers. (The hotel does not have to pay two commissions. It pays a single commission to the bedbank, which splits the commission with its own customer.)

With massive fragmentation on both sides – hundreds of thousands of hotels and many tens of thousands of customer groups – bedbanks play an essential role. It is not possible for all the parties to connect and contract directly, without scaled intermediaries.

Use case 1: independent hotels and the long tail

Bedbanks are especially helpful in connecting the long tail of small chains and independent hotels to all different types of customers.

While large travel agents and tour operators can easily sign direct contracts with the major hotel chains or properties their end-customers request most often, they need to rely on wholesalers in order to offer the long tail of other hotels in case needed.

Use case 2: international and transcontinental business

Hotels would like to attract visitors from different countries and even different continents, especially as these visitors may book earlier, stay longer and show lower price sensitivity.

But language, currency and credit risk may all pose barriers to signing direct contracts with even major travel retailers in the source countries.

Wholesalers can solve these problems through their global footprint and familiarity with managing all these risks.

Use case 3: rate parity and workarounds – the bedbanks’ secret sauce

Rate parity is a fact of life for hotels. It is a contractual agreement, insisted on by Booking and Expedia among others, to keep room rates the same across different booking channels.

As this article explains, rate parity clauses prevent hotels from selling rooms at cheaper prices on their own websites, which would save them commissions.

Positively, rate parity helps to maintain a hotel’s perceived brand value. If they are trying to sell rooms at $200 per night, then price consistency will reassure customers that this is the true and fair price.

In reality, though, hotels would like to maximise profits via price discrimination. Ideally, they would sell as many $200 rooms as possible to customers willing to pay full price, but then fill the remaining rooms at $100 per night rather than leave them unsold.

This is where bedbanks can help hotels to find special sources of demand, without violating rate parity clauses.

“Closed user groups” are member-based programs that provide discounted hotel rooms without advertising lower rates to the general public. Typical examples are employee benefit schemes or pay-to-join travel clubs.

See also frequent flyer or loyalty programs that let you burn points for hotel rooms, and package tour operators that bundle a hotel together with a flight or car rental.

All these channels allow hotels to offload cheap rooms, while maintaining plausible deniability about discounting the official rate.

Bedbanks help hotels connect to the myriad closed user groups and other special customers.

Bedbank market structure

The wholesale market makes up around 15% of the total hotel market. It is growing each year at a high single digit rate, supported by overall hotel market growth as well as growth in the three key use cases laid out above.

The top three hotel wholesalers globally are Expedia (via its B2B segment), Hotelbeds and Webjet’s WebBeds. These three players have only 50% market share between them. All are growing rapidly, at 20% or faster, taking share from the many smaller and marginal industry participants.

Hotel distribution is an incestuous industry, in which virtually every firm is both supplier and customer to every other. Hotelbeds will sometimes procure rooms from Expedia or WebBeds in cases where it lacks a direct contract with the hotel in question, and vice versa.

This interconnectedness, and the importance of relationships in the travel industry, mean that competition is not brutal or zero-sum in nature.

The table below summarises financials for the three leading hotel wholesalers. WebBeds is much smaller than the other two. All three have grown their TTV and EBITDA impressively in the most recent financial year compared to the pre-Covid year.

1. Expedia TTV for 2019 is gross bookings, disclosed in the June’22 presentation. Revenue and EBITDA for 2019 are adjusted for the disposal of Egencia, using 2019 Egencia financials disclosed on p537 of the GBTG prospectus. TTV for 2023 is estimated.

2. Hotelbeds financials are sourced from Companies House annual reports, converted to USD using monthly average FX rates

3. WebBeds financials are sourced from Webjet annual reports, converted to USD using monthly average FX rates

The WebBeds story

In 2011, as the new MD of Webjet and the former COO of GTA, Guscic would have recognised the company’s sole reliance on the Australian flight booking market as a significant weakness. He quickly set out to build a new offshore bedbank business inside Webjet.

Over time, he recruited many former GTA managers. WebBeds today has plenty of GTA DNA. This includes the CEO Daryl Lee, the Americas President James Phillips, the ME&A President Amr Ezzeldin, and the CIO Mohammed Malik. In addition, at Webjet group level, COO Shelley Beasley joined in Feb 2011 from a Travelport background.

From a standing start in 2012 and initial launch in 2013, his team used greenfield startups, rapid organic growth and key acquisitions to impressive effect. My chart below shows the development of total transaction value from nil to A$4bn. WebBed’s take rate (net revenue to TTV) is around 8%, and the EBITDA to TTV margin is around 4%, meaning the business earns an excellent 50% EBITDA margin on revenue.

The second part of the total return chart, from mid 2013 to present day, shows the journey has been profitable for investors, despite the intrusion of Covid.

See annex 1 for a detailed run through all the acquisitions that contributed to WebBeds. It is key to note that the final acquisition was made in November 2018. The growth that WebBeds has delivered from calendar 2019 to the Mar’24 year (TTV +46% and EBITDA +59% in USD terms) has been entirely organic.

The global breadth of WebBeds is equally impressive. Acquisitions were focused on Europe and the Middle East, which contributed 71% of TTV pre Covid. WebBeds has since built out a strong presence in North America and Asia (now 52% of total), almost entirely on a greenfield organic basis. See the chart below showing the changed geographic split.

In Asia, WebBeds is seeing strong growth in key markets of China, India and South Korea. In the Americas (mainly north America), new client wins and market share gains are driving growth.

Fuelled by this geographic expansion, WebBeds as a whole is displaying rapid organic growth momentum. Bookings rose by 26% yoy in Mar’24 over Mar’23, a comparison with very little benefit from Covid re-opening.

For the first seven weeks of FY25, Webjet announced that WebBeds is seeing bookings and TTV both up 35% yoy, with EBITDA “significantly ahead”. This is the momentum that prompted Guscic to burst into song on the earnings call.

See annex 2 for a portrait of Hotelbeds, the key peer and competitor to WebBeds which is based just down the road in Palma, Majorca.

Annex 3 provides a review of the many other competitors, potential challengers and listed peers.

Legacy Webjet – profitable but not in growth mode

Webjet is Australia’s top flight-oriented online travel agent. As my chart below shows, the business grew impressively until 2019. Since Covid hit, it has clawed its way back to the pre-Covid level. It is currently trending flat, as the focus is on absolute profitability rather than volume growth.

Thanks to twenty years of brand marketing, Webjet is top of mind for many Australians when it comes to booking flights. This has given the business a high market share and a favourable mix of direct and unpaid traffic, which supports excellent profitability.

Specifically, Webjet’s market share for flights among Australian online travel agents is c.50%. However, penetration of OTAs is lower in Australia compared to other countries. Webjet’s overall market share of all eligible flights (those on GDS systems, i.e. excluding LCCs) is 8.2%. This includes an 11% share of domestic bookings and a 4% share of international bookings (where Australians are more likely to turn to a traditional travel agent such as Flight Centre for help).

We have unusually precise colour on the sources of traffic for Webjet. A helpful January 2020 disclosure revealed the following split, which is likely stable from year to year.

· 33% from direct channels such as the app, email marketing or typing the website URL into the browser bar;

· 27% from Paid Brand, where the customer types Webjet (or similar) into Google and then clicks on the Webjet ad;

· 14% from Organic Brand, where the customer types Webjet into Google and then clicks on the organic search result for Webjet;

· 18% from Paid Non-Brand, where the customer types “flights to Bali” (or similar) into Google and then clicks on Webjet’s ad;

· and only 8% from Organic Non-Brand, which may be vulnerable to Google algorithm change.

This favourable mix of direct traffic allows Webjet to spend just 1.5% of TTV on marketing costs, far lower than for many other online travel businesses. Indeed, across the whole group, marketing expense was just A$26m in FY24, miniscule compared to EBITDA of A$188m. Webjet is far less of a “Google tax” victim than most OTAs.

As a result, Webjet’s B2C business made A$56m of EBITDA in FY24, which is a 3.5% margin compared to TTV or an impressive 39% margin compared to net revenue. This quite possibly makes Webjet the most profitable flight-oriented OTA in the world, given that flights are typically lower margin than hotels.

Recently, Webjet has made a deliberate push to increase share of international flight bookings. Webjet is deploying tech to support this. In 2021 it acquired the small Trip Ninja business which adds unique tools to help customers book open-jaw and multi-stop itineraries with mix’n’match airlines to find lower prices.

Increased international flight mix and growth in ancillaries (hotels, tours etc) is supporting absolute EBITDA in the B2C business, and offsetting headwinds from airlines’ reductions in commission structures, as well as recent falls in Australian flight prices after huge prior rises.

For the first seven weeks of FY25, Webjet’s booking volumes are flat and TTV is down 5% yoy. This reflects a 10% yoy fall in flight prices, offset by a further increase in mix of international flights for Webjet. EBITDA is tracking ahead yoy, despite the 5% fall in TTV, which is an encouraging start.

GoSee and Zuji – minor blemishes on the B2C business

As my chart above reflects, the B2C business also contains GoSee, a small New Zealand-based business focused on motorhomes and car rentals. GoSee was acquired in June 2016 as Online Republic for A$83m. It has turned out to be a poor acquisition.

Inbound tourism to New Zealand is in the doldrums, and GoSee’s competitive position is not the strongest. A New Zealand listed stock called Tourism Holdings (THL.NZ) is the leading motorhome rental provider, and it is down over 50% YTD on a brutal profit warning, reflecting the tough NZ market conditions.

GoSee is an asset-light business. The goodwill has already been impaired, and costs have been cut. It is currently operating on a breakeven basis.

In short, I see limited risk to the overall B2C segment from GoSee. The resilient and highly profitable Webjet business will be the key segment driver.

Of historic note only, in March 2013 Zuji was a poor B2C acquisition for A$24m. This was a HK and Singapore online travel agent, which was never competitive or meaningfully profitable. Webjet was fortunate to be able to sell Zuji in January 2017 forA $56m plus A$6m surplus cash adjustment. They even booked a gain on sale. Zuji then fell into bankruptcy in 2019, owing money – a lucky escape for Webjet.

The GoSee and Zuji experiences combined are likely to have cured the B2C business of any further M&A appetite. This is highly relevant for its prospects as a standalone listed business, because I see a good chance that it will take a disciplined capital allocation approach of paying out all free cash flow to shareholders.

Demerger considerations and mechanics

Webjet’s announcement that it is considering separating its two businesses is logical and welcome, in my view. The two divisions could not be more different, other than both operating in the broad sphere of travel booking.

Webjet is B2C, airline-oriented, focused entirely on Australia and New Zealand. WebBeds is B2B, hotel-focused and globally spread with key offices in Spain, London and Dubai, and almost no Australian presence.

More to the point, Webjet is mature and needs to be managed carefully for costs and cash, with the potential to pay out high shareholder returns. WebBeds, by contrast, is growing fast and has reinvestment opportunities at attractive returns, including organic technology investments and potential tech-based acquisitions. So it makes sense for the two businesses to get separate and appropriate management teams and capital allocation policies.

Separation is slated to take place before March 2025 if it goes ahead. Officially, no final decision has been made. This means that officially, no personnel decisions have been taken.

However, you don’t need to be Mystic Meg to predict that Guscic, currently aged 60, will choose to lead the WebBeds business. He lives in Majorca, where the business he built and championed is headquartered.

Meanwhile, Dave Galt has been CEO of the Webjet OTA business for 11 years, and would be the obvious choice to keep running it after separation.

There might be modest dis-synergies from separation, with doubled listco costs and possible higher remuneration for two sets of top brass. But this should be manageable.

Separation also brings increased potential for a bid for either business. For example, a light-hearted Skift travel industry article in Dec’21 imagined Amadeus as a possible suitor for WebBeds. A PE bidder might see Webjet as an attractive project, depending on valuation.

Demergers and spin-offs are in fashion worldwide. In Australia, the process is straightforward, with recent precedents as below. A shareholder vote on demerger is preceded by the publication of a 200-300pp booklet (not technically a prospectus, but it contains similar information).

· BHP Billiton demerged South32 back in May 2015.

· Iluka demerged Deterra in November 2020.

· Woolworths demerged Endeavour in July 2021.

· Tabcorp demerged The Lottery Corp in June 2022.

Financials

Webjet’s track record is fascinating. It has been a successful ride for investors overall, but far from flawless, with both triumphs and major setbacks along the way.

The operational story is the highlight, with both businesses having delivered profitable growth over the long term, including the outstanding creation and scaling of WebBeds from nothing.

Key complaints could include a mixed track record on M&A, and poor capital management including excessive issuance of new equity along the way – even before the hugely dilutive but necessary Covid rescue financings.

Corporate governance has felt immature at times, including a spate of notable accounting errors and finance cock-ups in 2016 and 2017 that preceded a change of CFO in 2018. (These included an accounting treatment dispute with their own auditor on a deal with Thomas Cook that I detail further in Annex 1, as well as the mistaken inclusion of D&A from prior to purchase of JacTravel; persistent rather large FX losses which demonstrated an ineffective approach to hedging; and delayed B2B payments due to a new ERP system.)

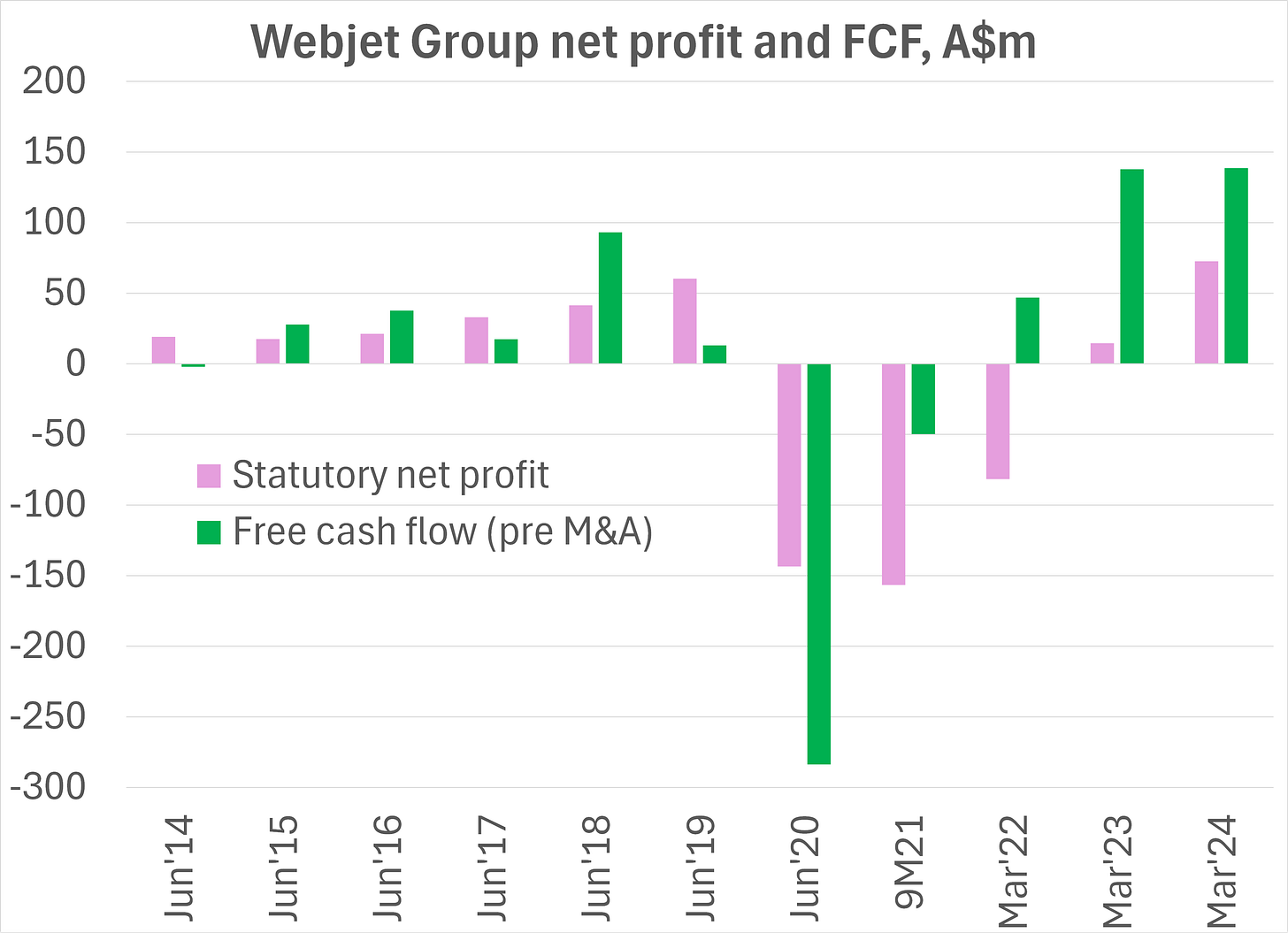

Some will also complain of a low quality of earnings, including historically lots of items and exceptionals between adjusted EBITDA and statutory net profit. My chart below shows impressive growth in revenue and adjusted EBITA, but statutory net profit that is negative by A$100m in cumulative terms over the entire 11 year track record period shown.

My response is to point out the huge roles played by Covid, as well as M&A and the process of building the WebBeds business from scratch in the previous eleven years. Yes, many eggs were broken, but a delicious omelette has been made.

Company-defined ROIC was 24% in FY24, sharply higher than 13% in FY23. This is defined as underlying NOPAT over average net debt plus equity. I would deduct the A$6.7m of share based payment expense, which still results in a strong 23% ROIC. Thanks to the blossoming of WebBeds, the group is being newly revealed as a high quality business that earns a return far above its cost of capital.

In considering whether to buy the stock today, I prefer to focus on net earnings and free cash flow on a forward basis. As I discuss in the next section on estimates and valuation, there is reason to be optimistic on both counts.

Nonetheless, for the record I continue to review the track record that got us to this point.

Specifically, statutory net profit was negative due to amortisation and impairment of acquired intangibles and goodwill. Free cash flow, defined as cash from operations less capex, was unaffected by the non-cash writedowns, and was significantly positive in cumulative terms. See chart, which also shows the pro-cyclical nature of working capital in a travel business.

Drilling further into FCF, the business is not very capex-intensive. My chart below shows that total capex of A$40m per annum is mainly spent on capitalised intangibles to support the growth of the IT-intensive WebBeds business. During the growth phase, capitalisation of intangibles is running moderately ahead of amortisation. A purist might wish to make an adjustment for this and treat all IT development as expensed. The delta to earnings would be only A$15m or so.

The chart below shows the cash spent on M&A, as well as the associated equity raises, and the huge A$334m net equity raise undertaken in April 2020. Not included are the receipts from two convertibles. They issued a €100m convertible note in July 2020. This was subsequently converted to 39.7m shares in April 2021, on payment by Webjet to the noteholders of a A$33.2m incentive fee. They issued a further A$250m convertible note issued in April 2021, which remains outstanding until 2026. The board has suspended dividends until it learns whether the A$250m note will be repaid in cash or converted to equity. My estimates factor in dilution from conversion.

The upshot of the substantial sums raised from equity and convertibles in 2020 and 2021, followed by the strongly positive free cash flow of FY22 to FY24, has been to leave Webjet with a belatedly very strong balance sheet position. Net cash stood at A$406m at March 2024, calculated as A$630m of own cash, less A$224m debt component of the outstanding convertible note. No other debt is outstanding.

Key management personnel remuneration is not unreasonable. The total for three executives plus all non-executive directors in FY24 was A$8.4m, which equates to 5.3% of EBIT. Performance metrics for the STI and LTI were mainly based on EBIT growth, plus a TSR component on the LTI.

Estimates and valuation

I forecast the B2B business to compound earnings at 23% from FY24-28E. For the B2C business, I forecast 3% earnings growth on a flat top line. See my estimates below.

The valuation looks attractive relative to the forecast growth. On a consolidated basis, I see the stock trading on 22.5x current P/E falling to 15.2x Mar’27E P/E. The stock is potentially on a free cash flow yield of 5.5% for Mar’27E, even allowing for a conservative FCF conversion on potential headwind from a B2B working capital increase.

Historically the stock has tended to trade anywhere in the 15x to 30x range, excluding the Covid era. The current valuation sits comfortably in the middle of the range. See chart below.

If the separation goes ahead, then I would expect the Webjet B2C business (23% of total profits) to trade on a mid to high teens multiple, while the fast-growing B2B business (77% of total profits, assuming the corporate cost is allocated entirely to B2B) could re-rate into the mid to high 20s.

Conservatively, multiples of 13x and 26x for the two separate businesses would solve for the current blended 22.5x rating, while if the market valued either separate business more highly then this would provide re-rating upside.

Even without any re-rating, I anticipate a pleasant 22% IRR from earnings growth alone.

Annex 1. WebBeds history: the fast follower

In 2012, as the new MD of WebBeds and the former COO of GTA, Guscic quickly set out to build a new bedbank business within Webjet.

The first move was organic. In February 2013 the team launched Lots of Hotels as a start-up based in Dubai, providing customers in countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait and Jordan with hotels worldwide.

On 1 July 2014 Webjet purchased the SunHotels Group for €18.2m ($A26m). This was a Spanish provider with key strength in Mediterranean and beach properties, and market leadership in Nordic countries and the UK. It was bought as an established and profitable business with €2.6m EBITDA, therefore qualifying as a cheap and favourable acquisition.

Like Hotelbeds, SunHotels was based in Palma, Majorca, which is a travel industry hub. Guscic relocated there soon after acquisition in order to focus on building up Webjet’s B2B business.

November 2015 saw the next milestone, with the organic launch of Lots of Hotels into the US, Canada and Latin America. This launch would prove to be a very slow burn, but one that has recently come good with America now delivering strong profitable organic growth.

In August 2016 they announced a strategic sourcing partnership with Thomas Cook, paying £21m to receive 3,000 hotel contracts. This deal was a dud. It is most notable for triggering a bust-up with then-auditor BDO on the accounting treatment, which led to a humiliating climbdown and an A$11.5m hole in FY17 profits. A new CFO and a change of auditor from BDO to Deloitte followed swiftly. The dark humour is that under the new accounting treatment, only costs would be incurred until June 2019. From July 2019 onwards, substantial profits were anticipated. Sadly Thomas Cook entered compulsory liquidation on 23 September 2019, with the write-off of €27m of unpaid receivables.

In November 2016 they announced the organic launch of FIT Ruums as a start-up to serve the fast-growing Asian B2B market. There was a supposed exclusive partnership with DIDATravel, which is China’s biggest hotel wholesaler or bedbank. The DIDA partnership never really went anywhere, but the Asian launch itself has, like America, gathered great momentum to become a major and ongoing success.

In August 2017 Webjet announced the acquisition of JacTravel, a market leading European B2B travel business. JacTravel’s £400m TTV more than doubled the B2B business, and made WebBeds the #2 bedbank player globally and in Europe. JacTravel had been a project put together by PE firm Vitruvian Partners from 2014. They bolted on TotalStay to the existing JacTravel business to bulk it up. The price of £200m represented 10.5x adjusted FY17 EBITDA and was estimated to be 25% EPS accretive on pro-forma basis. The deal was funded by a A$164m share offer at A$10 per share, A$100m debt funding and A$45m existing cash reserves. Webjet also issued 2.6m new Webjet shares to continuing JacTravel management and the PE vendor – equivalent to 2% of issued capital. (They shouldn’t have bothered, since none of the incentivised management team stayed in the group for longer than a year or so.)

While the JacTravel deal was not cheap, it was successful in increasing the proportion of directly contracted hotels within WebBeds. This in turn supported the excellent profitability levels that WebBeds has now reached.

In November 2018 they acquired Destinations of the World (DOTW), a leading Dubai B2B business, from regional PE firm Gulf Capital. DOTW was founded in 1994, and doubled in size from 2013 to 2018 thanks to organic expansion and bolt-on acquisitions. They paid USD173m (A$240m) plus a USD25m earn-out, or 11x trailing EBITDA. This deal had a similar rationale to JacTravel.

Management have been explicit that they now have near to full global coverage, and they do not plan to buy any more scale in the mould of the JacTravel and DOTW deals. The future growth of WebBeds is expected to be mainly organic. Potential smaller acquisitions would be technology or product-based deals that add a unique capability, or regional deals in LatAm or Eastern Europe, the only two regions of notable under-penetration for WebBeds.

Annex 2. Hotelbeds: the leading pureplay bedbank

Hotelbeds is by far the biggest independent global bedbank. It was stitched together by private equity from three regional players in 2016. The owners are keen to exit via IPO, possibly in Madrid, but this was recently delayed until the end of 2024 or 2025.

Fortunately for us, Hotelbeds have published full annual reports and accounts each year in UK Companies House, giving great visibility into WebBeds’ key competitor.

It started in September 2016, when a Cinven and CPPIB consortium bought Hotelbeds from TUI for €1,233m. Based in Palma, Majorca, this business was strong in Europe.

In June 2017 they bought Tourico Holidays, an Orlando, Florida based bedbank business, giving a strong North American presence.

In October 2017 Hotelbeds acquired the GTA bedbank from Kuoni. This business had a strong presence in APAC and Middle East. (Webjet MD John Guscic was a driving force in building the GTA business up to 2011, when Travelport sold it to Kuoni.)

In the year to Sep’19, Hotelbeds handled €6bn of total transaction value. Revenue was €819m and adjusted EBITDA was €237m. This was actually a down-year compared to Sep’18. The business apparently ran into some headwinds when it was found to have been supplying discounted wholesale rates that were ending up on public sale, in violation of rate parity clauses.

Covid then intervened. By Sep’23 Hotelbeds had recovered to €8.1bn of TTV, just €656m of revenue and €354m of EBITDA. This suggested it had lowered its take rates but also cut its own costs compared to the pre-Covid result.

In profitability terms, Hotelbeds has sometimes been described as a higher-cost and lower-margin operation compared to the more agile WebBeds. However, the numbers I have seen don’t bear this out, with both businesses now enjoying comparable and high profitability.

Annex 3. Broad competitor and peer set, with brief comments.

Thanks to Tegus for help identifying the companies listed below.

TBO TEK (Travel Boutique Online) is an Indian wholesale travel business that just launched a successful IPO in May 2024. The ticket is TBOTEK.NS, and the market cap is USD2.0bn. TBO looks to be an interesting business to follow, with currently 56% exposure to India and 50% to flights, but also an emerging overseas wholesale hotels business that overlaps directly with Hotelbeds and WebBeds in certain regions. TBO’s investor presentation shows a low 5.2% revenue margin and 1.0% EBITDA margin as a proportion of gross transaction value, suggesting poor monetisation and high costs at present.

Sightminder (SDR.AX, USD868m mkt cap) is an Australian listed hotel management software business that is adjacent to WebBeds. It provides hotels with a system that helps them to manage and optimise their tariffs across all different platforms, including direct contracts and via wholesalers. Sightminder is not yet profitable and is not growing especially fast, making it a precarious SaaS investment proposition for the optimistically minded.

Hopper is a whizzy US travel and fintech startup that raised over $700m at valuations of up to $5bn. It has both B2C and B2B markets. But more recently, in September 2023 it laid off 30% of its employees to try to become profitable. At around the same time, Hopper terminated its supply agreement with Booking, and started new supply agreements with Hotelbeds and WebBeds.

Omnibees of Brazil claims R$16bn (USD3bn) of TTV and 24m room nights per year, making it a significant regional player. It is still private, and would be a potential IPO to watch.

HyperGuest of Israel raised $23m in Series A in July 2023, and aims to disrupt the wholesale hotel market but with limited sign of impact so far.

HotelRunner, in London and Turkey, is slightly scaled, with >100 staff. They raised a $6.5m Series A in Jan 2023. They try to offer a SaaS-based solution to wholesale hotel bookings.

RateHawk is said to have reached USD124m revenue in 2022 with a 387-strong team. It is owned by Emerging Travel Group, a leading Russian travel tech co. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, RateHawk was threatened with boycott in Poland.

HotelTrader is a pretender that wants to provide a tech based solution and full transparency between hotel and customer, but has failed to scale with a miniscule “500+ properties and 45+ leading travel agencies already connected” quoted on its website FAQs.

Impala Travel Technology appears to have burnt through £25m of funds and failed to make any impact, cutting employee numbers from 47 in 2022 to 8 in 2023 according to its accounts, and pivoting away from a bedbank model.

Collectively, the firms above provide a nice ‘moat attack’ case study per Polen Capital’s podcast episode – see extracts below.

[Moat Attack]

“There is a theory you can’t truly know the moat or barriers to entry exist until that moat is attacked and the attack is repelled. The bigger and more well-capitalised the attacker the better. I think of capitalism like nature, it’s just a brutal place; these attacks are happening all the time. This isn’t a concept that has any absolutism but I do think it is a useful tool. When these things happen there is something probably there. We don’t have any black boxes at Polen. You can open up the Financial Times and see that there is a large company attacking a company or partnering with a company to attack a company and investigate it, ask why?” Jeff Mueller

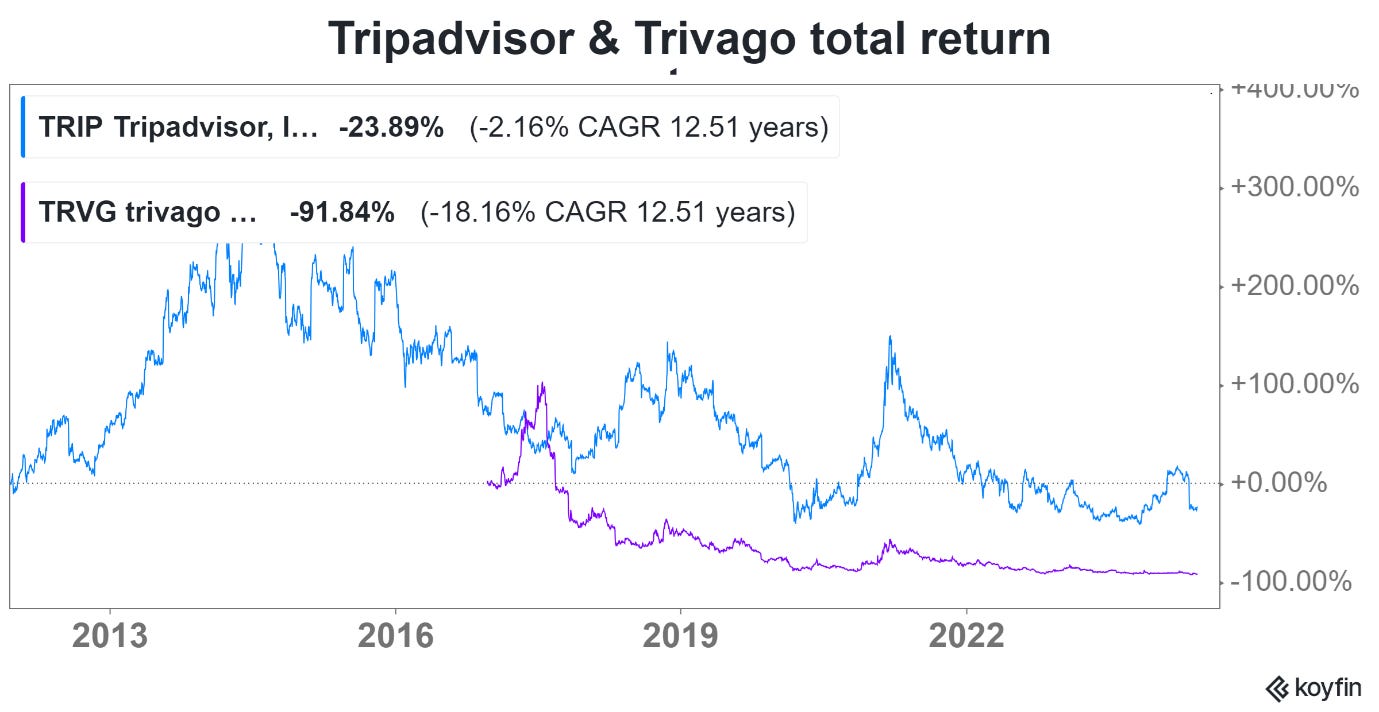

Meanwhile, the aggregators or metasearch players were hot news in the online travel industry ten or so years ago. But this model now looks like a relative loser. These companies tried to compete against Google head-on, and made little impact.

I include Tripadvisor (independent), Trivago (controlled by Expedia and separately listed) and Kayak (owned by Booking) in this category. The stock prices speak for themselves – see chart below.

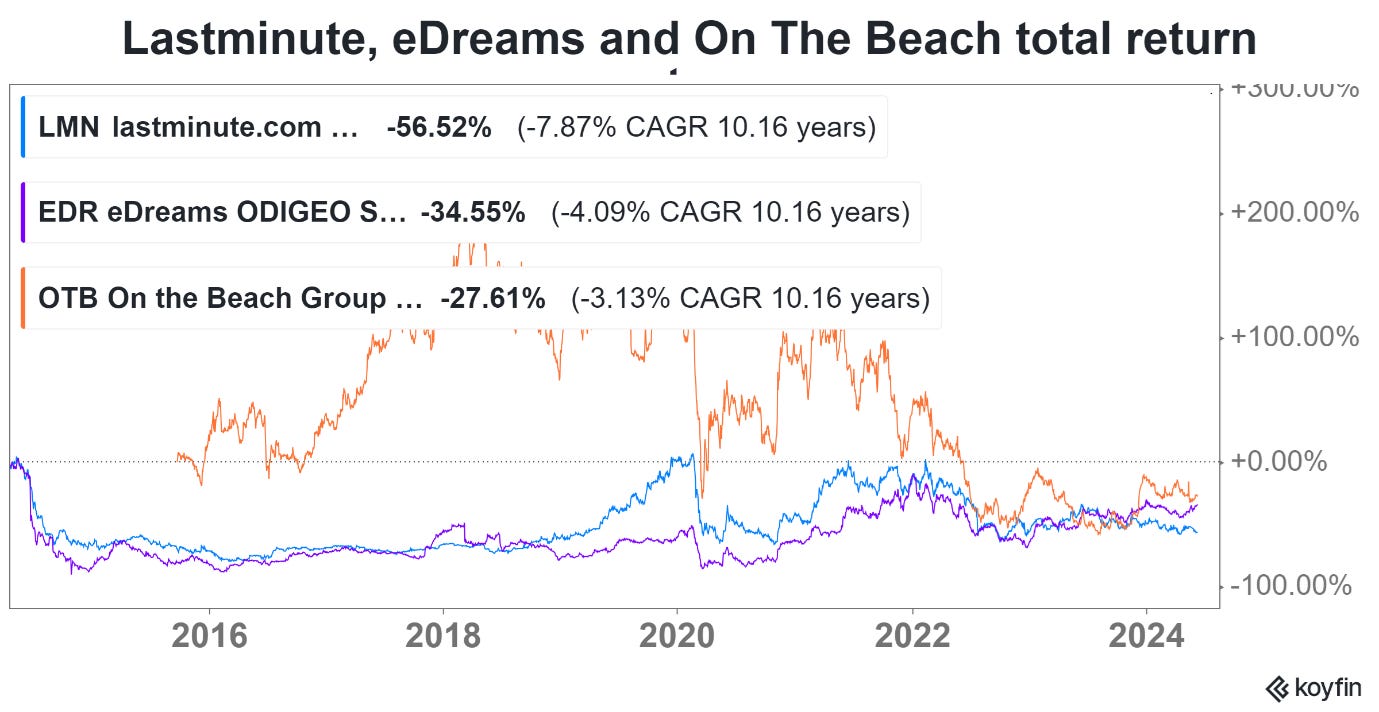

Last and least, I am wary of any unscaled and undifferentiated small cap online travel agent. One would always need to understand how they could win against the three American giants, i.e. Booking, Expedia and Google.

In this category I include Lastminute.com, eDreams, and possibly On The Beach – see chart below. (Despegar and Trip.com might be better with sufficient scale in their markets – I don’t know them well.)