The mild-mannered scientist has an urgent need to make serious money. He immediately thinks of the high-value crystal. Dare he take on the intimidating outfit that has monopolised the market for decades?

He tinkers away, and comes up with a new and superior recipe to cook the stuff to greater purity than ever before. Clients are blown away when they receive samples. They demand more.

Now he needs to cook at scale. With his partner’s backing, he fits out a top secret, purpose-built laboratory within the perimeter of an existing, legitimate-looking business.

This is not Albuquerque, but Stoke-on-Trent. Goodwin’s entry into the high-purity polyimide resin market (with a crystalline structure), while not illegal, is every bit as audacious as Walter White’s career move – and could prove equally as lucrative.

Goodwin is a 140 year old engineering firm. The fifth and sixth generations of family directors own 54%. They have proved to be talented entrepreneurs and capital allocators. Since the early 1990s they have reinvented Goodwin several times over, driving waves of profitable growth. The fruits of the latest reincarnation are imminent.

The stock is a UK private investor favourite, and has just gained re-entry to the FTSE All-Share index, having been kicked out two years ago when it failed the liquidity test. In market cap terms it is now knocking on the door of the FTSE 250.

Yet it has zero broker coverage, and is virtually unknown by the institutional buy side, for whom it has been too illiquid to consider.

As such there is an information vacuum around Goodwin (with the exception of Richard Beddard’s excellent Oct’23 write-up), and a complete lack of any forecasts whatsoever.

In this write-up I aim to address that vacuum. The post is structured as follows.

· History and brief track record

· Current shape of the business

· Forecast scenarios, broken down into seven potential growth drivers

· Detailed business reviews and workings for each growth driver

· Financial track record, balance sheet and cash flow factors

· Valuation thoughts, including peer comparisons

· Annex on management and their long-term approach

Nothing in Sweet Stocks is ever investing advice. This disclaimer especially applies here. In providing my description of the businesses, my estimates and thoughts on valuation, I am presenting scenarios in good faith, based on what I have been able to learn about the company. However, I have not yet had the opportunity to speak to management, nor to visit Goodwin’s facilities. I aim to remedy this in the months ahead.

I hold Goodwin as a top five position, which I accumulated over the last six months or so. That is the luxury of my current status as a private investor. I acknowledge to my institutional readers that the stock is still highly illiquid. I expect this to improve in future.

History and brief track record

Goodwin was founded in 1883 in Stoke on Trent, and the business has been casting metals on the same site ever since. It listed on the London Stock Exchange in 1958.

From the mid 1970s onwards, Goodwin was struggling. Its mainstay products were radial tyre building machinery sold to British tyre makers and refractories sold to British steelmakers. Both sets of customers stopped investing, and over time most shut down completely.

Scrambling for work, Goodwin pivoted to making specialised valves for the petrochemical industry, as well as slurry pumps for mining. These new lines kept the foundry and machine shop busy. However, the products were made under licence from American firms, with Goodwin’s sales territory restricted to Europe. Much of the trading profit was repatriated to the licensors as licence fees. Group profit before tax averaged just £300,000 per year in the ten years from 1985, for a 2.6% average margin on sales.

By the mid 1990s, thanks to patient and focused efforts, Goodwin had designed and developed its own range of products that were technically and commercially competitive, patented, and could be sold worldwide with no licence fees payable.

My chart below shows 1995 as a turning point, with rapid sales growth and far stronger profit margins from this point on.

Increased exports were key to the turnaround. My chart below shows UK sales fell from over 70% of sales in the early 1990s to less than half by 1996.

From 2001 to 2014, Goodwin saw meteoric growth in valve sales to the oil, gas, petrochemical and power generation industries, like a miniature version of Rotork, IMI or Weir. Emerging market sales were especially strong. Goodwin developed cutting edge products such as very large nickel superalloy castings for ultra-supercritical coal power stations

However, from 2015, demand from these energy markets collapsed, never to return to the same level for Goodwin.

Fortunately, Goodwin’s talented directors had been busy with a number of diversifications. Some have already contributed to replace the missing energy profits. Others are in the late stages of development, and about to hit the P&L in a big way.

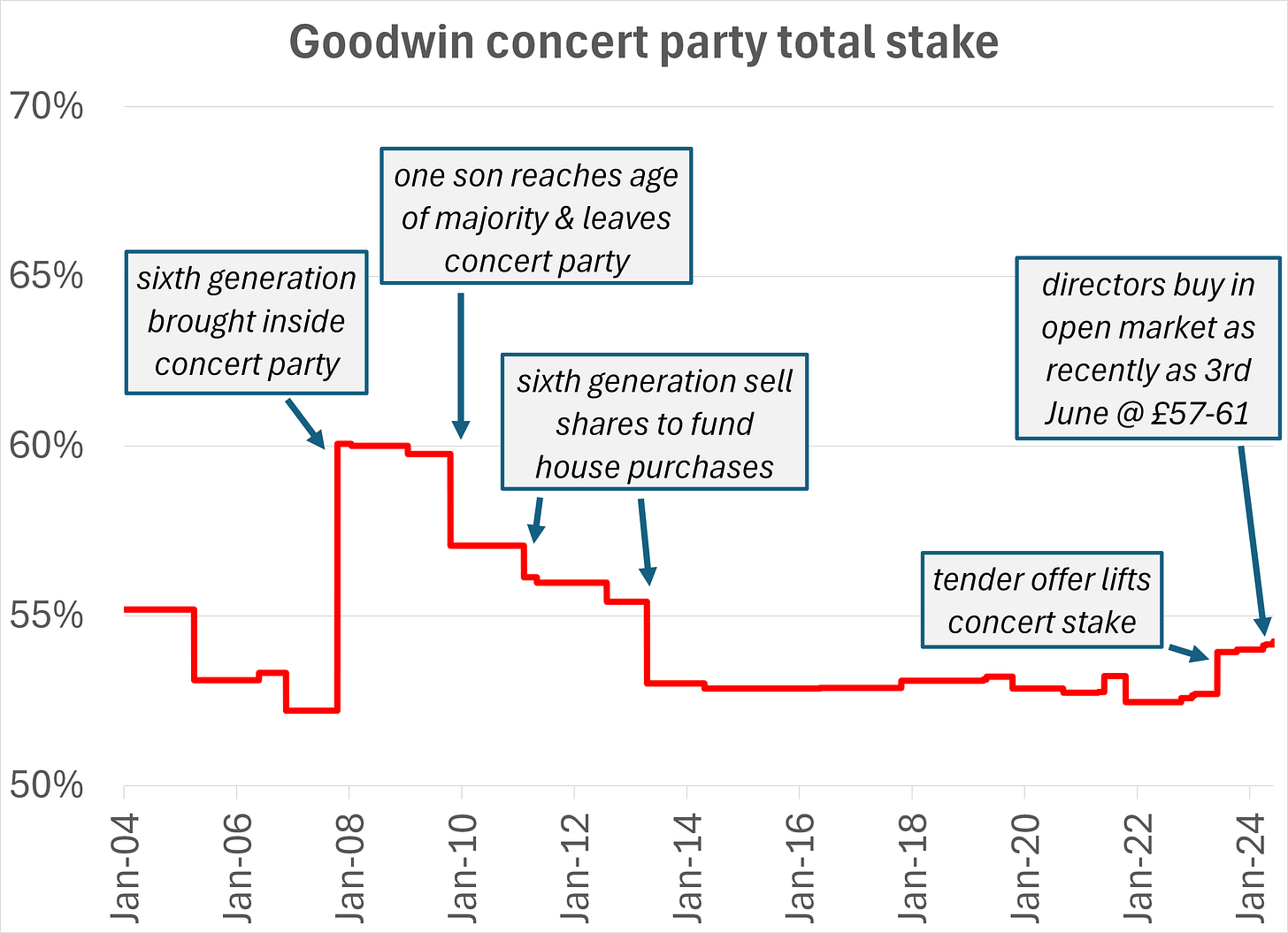

It is noteworthy that the six Goodwin family members who are executive directors and former executive directors have been purchasing shares in the open market for the last several years. They bought shares as recently as June 3 2024, and have paid prices as high as £61.50 per share. They also undertook a 2.3% off-market buyback last year via a tender offer at £48 per share (which seemed a high price at the time). They did not participate in the tender, effectively increasing their stake.

See my chart below for changes in the concert party stake over time.

Current shape of the business

Since 2009, Goodwin has reported sales and profits in two segments, Mechanical Engineering and Refractory Engineering. My chart below shows the profit split by segment.

The Mechanical segment includes the foundry (Goodwin Steel Castings) and machine shops (Goodwin International and Noreva GmbH). It sells the valves for the oil & gas and energy industries, as well as slurry pumps for mining and large and specialised castings for construction, shipbuilding and nuclear uses. The big 2014 peak from energy sales is obvious on the chart. Easat turnkey radar systems and the Duvelco engineering plastics start-up also sit in the Mechanical division.

Refractory includes casting plasters, injection waxes and molding rubbers for the jewellery industry, as well as a range of niche products derived from cristobalite, perlite and exfoliated vermiculite. This division includes AVD fire extinguishing agents approved for lithium-ion battery fires.

Refractory profits have picked up the slack from Mechanical, as can be seen in the chart above. Up to now the jewellery businesses have been key to Refractory profit growth. Goodwin was early and successful in moving this activity from the UK to India, China and Thailand, lowering costs and getting closer to their jewellery-making customers in those countries.

This is just one of the hard-to-credit aspects of the Goodwin story. It was tiny when it established the network of Asian subsidiaries. It is almost unheard-of for UK businesses of Goodwin’s size at the time to launch full-fledged greenfield manufacturing operations overseas… let alone to make a full success of them.

After the December 2017 exit of previous top US rival Kerr from the market, Goodwin has dominated with an estimated 80% global market share and improved margins.

Alongside sales and profits, Goodwin reports its workload, or forward order book. This is sometimes provided as an April 30 year end figure, and sometimes as an “at the time of writing” figure in August. My chart below shows that Goodwin has seen a jump in order book cover since FY19, when it started winning multi-year orders for naval and nuclear castings from US and UK customers.

Forecast scenarios

No brokers cover Goodwin, and no forecasts are available. My key task in this write-up is to construct my own forecast scenarios. I have provided evidence and comments to support my estimates. I would greatly welcome detailed input from others in the comments. Do not rely on these estimates to make an investment. Do your own research.

For my base case, I focus on what could be achieved in FY26E, the year ending in April 2026. I have presented my estimates in terms of the established business, as well as incremental contributions from a number of live development opportunities.

I also include a cautious scenario – effectively the current level of profits if nothing works out – as well as a blue sky scenario, estimating a maximum profit impact of each growth driver with no particular date attached.

See the summary table below.

Established business

Goodwin has already finished its April 2024 financial year. It is due to report the results in early August. Based on the trading update provided on March 14, Goodwin delivered H2 profits “similar to the first six months”. Operating profit in the first half was £12.5m, so the guidance is for a record result of around £25m for FY24, up 23% year-on-year.

The Mechanical division has been responsible for the strong profit growth. Naval castings, nuclear waste containment products and slurry pumps have already been in growth and contributed to the record c.£25m result in FY24.

In my base scenario, I hold the established business flat in FY26E.

Duvelco polyimide

This is the biggest example of Goodwin’s ambition and ingenuity. Via a new 100%-owned subsidiary called Duvelco, they have invested c.£14m to build a greenfield plant for production of polyimide polymer resins, a top grade engineering plastic for high temperature and critical applications.

In the FY22 annual report they explained the project as follows:

“[W]e have developed the product and a process that will allow us to deliver a higher performing directly comparable polyimide polymer than the market leader. With an annual addressable, and growing, market size bigger than any product that the Group has supplied to before, the Board believes that, with limited existing market competition, a very high technology barrier, coupled with the fact we have a patent pending process that gives us markedly better high temperature performance than anybody else for directly comparable chemistry product, this should hopefully give Duvelco Limited, as a market invader, good prospects of long term success, so that one day it should be a major contributor to Group profitability.

As of the last update in December 2023, the plant was due to be commissioned and operational in June 2024, i.e. this month. I am confident that this timeline has been met. The website is here: Duvelco’s product is called Ducoya.

The giant in their cross-hairs is Dupont’s Vespel franchise. Vespel is a crown jewel business that sits within the $2bn Industrial Solutions business unit of Dupont’s Electronics & Industrials segment. I estimate Vespel annual sales at c.$400m, based on a disclosure given to JPMorgan analyst Stephen Tusa in March 2022 that the three growth businesses of Kalrez, Vespel and biopharma totaled $750m sales at that time.

Dupont have disclosed a split for Vespel by industry of over 40% aerospace, 25% automotive (both EV and ICE), with the remainder split between semiconductor and industrial applications.

Vespel has been a highly profitable growth franchise for Dupont, with a margin significantly higher than the 31% EBITDA margin enjoyed by the E&I segment overall. Growth has compounded at a double-digit rate since at least 2015, based on comments Dupont made at its November 2018 investor day. This growth required a significant expansion of polyimide resin capacity in 2021 to support Dupont’s downstream parts and shapes manufacturing process.

Dupont have on multiple occasions told their investors that Vespel is a competitor to Victrex’s PEEK in some respects. Victrex (VCT.L) had a group revenue of £307m in FY23, putting it at a similar scale to Vespel on my estimate. Victrex revenue has gone backwards since they did £326m in FY18, in stark contrast to Vespel’s sustained double-digit growth. It looks like Vespel is taking share from Victrex, to the extent that the two different materials are in direct competition. However, Victrex shipped 3.6kt of material in FY23 for an implied per kg price of £85. Some of the material was used in lower-end applications such as consumer electronics. Vespel, which Dupont provides in downstream shapes and customised parts for highly demanding applications, sells at a much higher average price.

It is beyond audacious for Goodwin, as a Stoke-on-Trent based steel and refractories company, to presume to enter this market with a greenfield start-up. And yet that is exactly what they are doing. The driving force of the project is Matthew Goodwin, who joined the main board in 2007 aged 26, having graduated from Imperial College as a material science engineer.

Their full patent application cites Dupont’s Vespel and also Saint-Gobain’s Meldin 7000 range as prior art. (Vespel’s original patent long since expired.) Goodwin is seeking patent protection for its new and superior method for treating polyimide, claiming reduced volatile organic compound use, enhanced solvent recovery, higher purity and better elevated temperature mechanical properties, compared to Vespel and Meldin grades.

Goodwin will likely target the semiconductor industry as initial customers, since they may especially appreciate the higher purity level, which could induce them to switch quickly if it supports higher yields in their production process. This article from a Meldin distributor provides some useful colour on the specific applications of Vespel within plasma deposition chambers. Aerospace customers, by contrast, are likely to be risk-averse and slow to make any changes to their existing use of Vespel.

It is natural to be sceptical about Goodwin’s chances of success in disrupting Dupont, but they appear to be serious. Their initial stated ambition is for £40m of annual revenue, based on the capacity they have installed. Their cover letter and detailed application to the Environment Agency sought a permit for up to 95 tonnes per year of capacity, which was duly granted. The initial installation has 40t of capacity. Most notably, in December’s half-year report, they stated that “all initial chemicals to make up to 30 tonnes of polymer resin are on site”. In my view, this is a step they would only have taken after receiving positive indications from extensive engagement with potential customers.

The German press reported last month that Goodwin’s German machining business, Noreva, is investing €4m to build a factory extension to machine parts made of Ducoya.

If Goodwin succeed in reaching their £40m initial sales target, then the margin potential should be 30% or higher, based on the high margins enjoyed by both Vespel and Victrex.

I pencil in an £8m profit contribution for my base case, with £18m blue sky potential. Clearly this is subject to binary risk in terms of a successful commercial launch. The update in August should give a clear indication whether this is on track.

Naval components

Goodwin has been understandably reticent to provide public detail of specific naval contracts. Back in 2017 they mentioned US submarines and UK Type 26 frigates. My understanding is that in the period since then, they have won several additional supply agreements with different US prime contractors on various platforms. They appear to have built a reputation for on-time delivery of high-value, large and complex castings with a capability to provide full testing, validation and compliance documentation.

The separate sales and profit margin for the Goodwin Steel Castings foundry subsidiary are shown in the chart below. A recent pickup in growth is visible. Profitability was yet to recover fully as of April 2023.

In my base forecast, I pencil in a £4m incremental OP contribution in FY26E. This is a placeholder to represent the long-term growth opportunity for Goodwin in this category, as projects such as AUKUS submarines come into view.

Nuclear waste

Goodwin has commented publicly on three separate nuclear waste orders, detailed below. They are likely to have won other work in this category as well.

· In August 2019 in the annual report they wrote about a “multi-million dollar order Goodwin Steel Castings has received […] for cast and machined radiation shielding containment vessels for the USA nuclear decommissioning market”.

· In June 2020 they issued an RNS announcing “a long-term arrangement to manufacture and machine storage boxes to assist with nuclear waste clean-up. The production programme is planned to ramp up over a 12 month period, and is anticipated to continue for many years. Goodwin Steel Castings Limited will manufacture castings for the project, with other activities being undertaken at Goodwin International Limited. This is the largest purchase agreement the Group has entered into to date, and is expected to result in significant turnover for the business from the next financial year onwards”.

· In August 2022 in the annual report they wrote “Goodwin International Limited has successfully tendered and been awarded 50% of the initial phase of the multi year multi million pound Sellafield Hybrid 2, 63 Can Racks as reported on the OJEU website in October last year. Gaining initial process and documentation approvals to proceed with manufacture will take time, but once ramped up, the initial production rate will be 20 racks per year, with 80 racks currently committed. Our customer has the option within the contract to make further commitment(s) of up to an additional 160 racks, as well as increasing the demand to 40 racks per year”.

The second of these contracts is probably the most significant. These are 30 tonne Self Shielded Boxes (SSBs) for Sellafield, with Westinghouse as the prime contractor and Goodwin the sub-contractor. Sellafield will eventually need 1,000 or more of these boxes to store intermediate level nuclear waste, initially on site and ultimately in underground chambers.

Goodwin are the only UK company with the capability to produce the SSBs. They are not to be confused with the different waste containment products being made for Sellafield by Avingtrans (AVG.L), Carrs (CARR.L) and Renew (RNWH.L).

The SSB contract has taken a long time to start up and ramp up, with an initial 4 to 6 boxes produced per month (likely to be reflected in the FY24 results) and a targeted run rate of 10 per month. With healthy pricing, the contract should provide a predictable base level of sales for the foundry for many years or decades to come. This should be additive to the prior c.£20m annual revenue of Goodwin Steel Castings, and can be transformative to foundry profitability. I estimate margins on the SSBs to be favourable, presumably with scope to improve on a learning curve.

The chart below shows the Goodwin International machining subsidiary sales and profit margin. FY23 saw the best sales since 2016.

In my base forecast, I allow a £3m incremental OP contribution in FY26E from the ramp up of the nuclear contracts.

Slurry pumps

Goodwin’s submersible slurry pumps for worldwide mining use are a long-standing product range. They utilise castings from the Stoke-on-Trent foundry. Since 2005, final assembly has taken place in Goodwin’s own factory in India. Sales, service and maintenance facilities are strategically located in the UK, India, Australia, South Africa, Brazil and Indonesia.

The pumps business has been performing strongly of late, and reached 12% of total group sales in the first half of FY24, after three years of 18% compound growth. While many competitor pumps are available, Goodwin say that they have been winning market share due to their higher reliability and robustness.

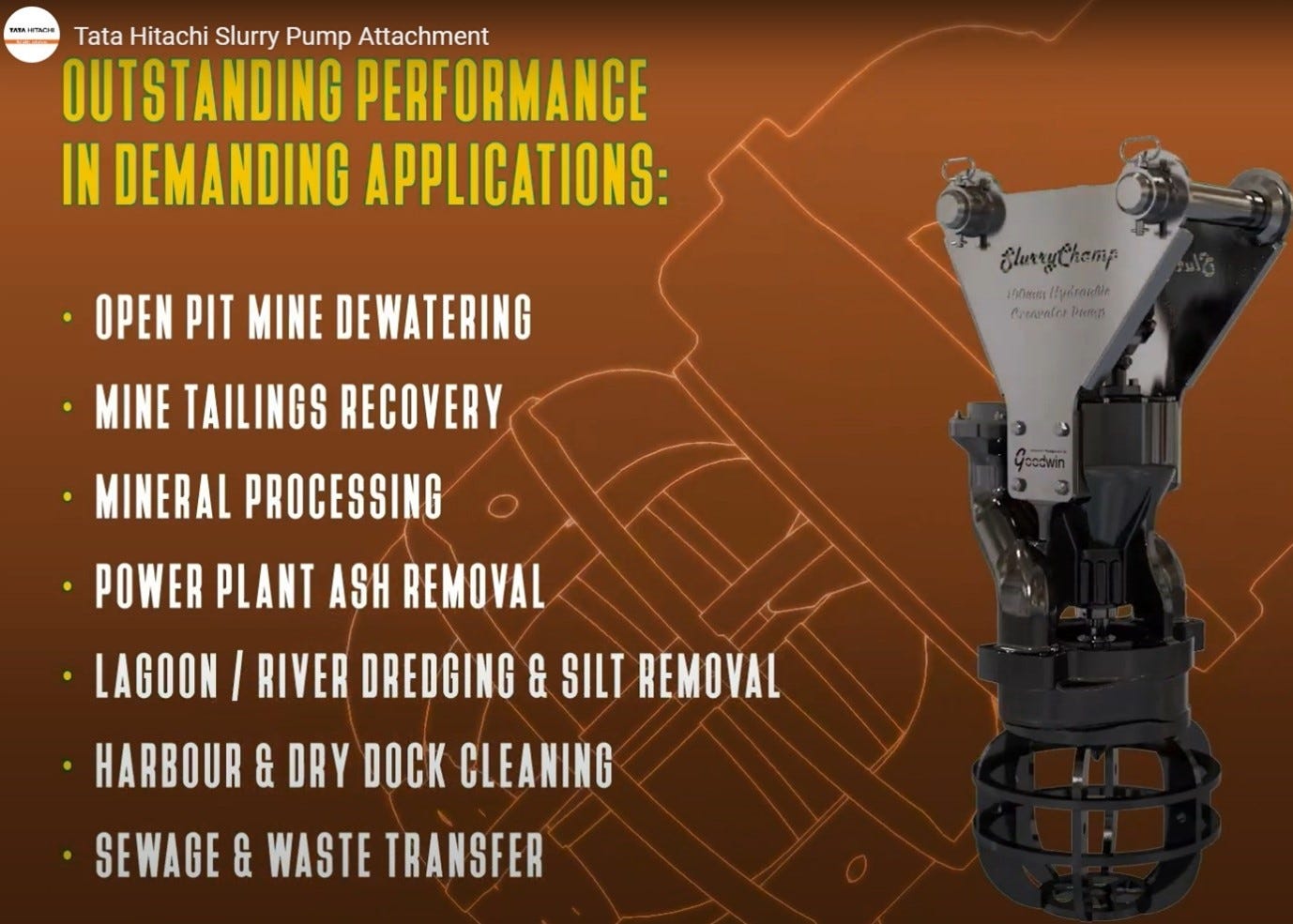

A possible game-changer has been the new SlurryChamp range of hydraulic pumps that are mounted on an excavator arm. First launched in 2022, these are sold by the excavator dealers as an attachment, meaning a low cost of sale and a high margin for Goodwin. E.g. Tata Hitachi, the large dealership JV selling Hitachi construction equipment to India’s mining and infrastructure markets, offers it for sale.

Goodwin is doubling the capacity of its Chennai factory, based on higher expected demand for the new pump range.

I include a £3m incremental contribution from pumps in my forecast.

Air traffic control

Easat was founded in 1987 as a maker of antennas for radar systems. In impressive fashion, Goodwin have developed the product offering over the decades. In 2015 they acquired NRPL in Finland. This, followed by design enhancements to their transceivers and interrogators, has allowed them to move from selling only mechanical parts to offering complete turnkey air traffic control systems. Such systems are supposed to have over 10x the original component value, and good margin potential. A recent win in Cranfield is an example of Easat’s technological prowess, providing a system that can handle unmanned aircraft systems and urban air vehicles, of the type that Joby (JOBY), Archer (ACHR) and Vertical Aerospace (EVTL) are seeking to develop.

However, several large orders have been long awaited and not yet confirmed. Delays in tendering processes have proved frustrating, even when Goodwin believed that Easat was in a winning position. With potential customers being state-owned entities in countries such as Nigeria, Libya and India, procurement processes are lengthy and politically charged.

A key incumbent and competitor is Indra (IDR.MC), the $3.7bn Spanish national defence champion in the making. Its Air Traffic Control division is the #1 across Europe, Middle East / Africa and Latin America. It had €361m sales and a 12% OP margin in 2023, to give a sense of the market opportunity for Easat if it can establish itself. Indra is ambitious to further improve and grow its ATC business, and just spent €50m on two bolt-on acquisitions to expand in North America.

In the five years from FY19 to FY23, Easat averaged below £10m sales per annum and had a cumulative £3.6m operating loss – see chart below. This is a good example of Goodwin’s ability to deliver strong results at group level even while absorbing development losses in certain areas.

I pencil in a £2m incremental profit contribution from Easat in my base case, with £10m of blue sky potential and plenty of uncertainty.

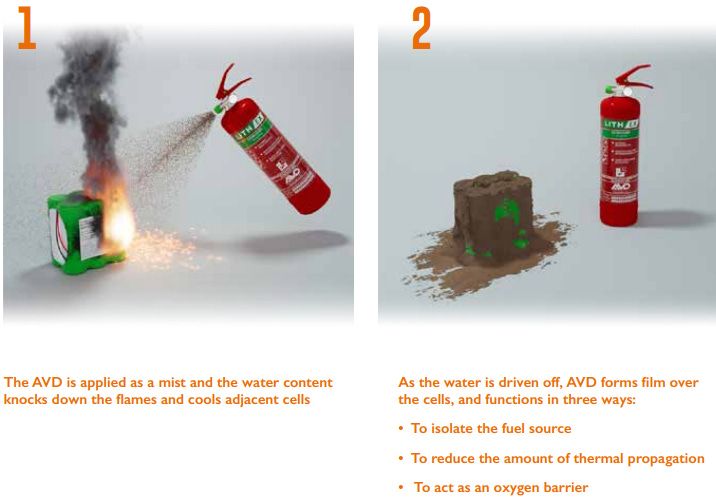

AVD fire extinguishing agent for lithium ion battery fires

While all the growth drivers above sit in the Mechanical division, AVD is the sole Refractory driver that I have separately identified. AVD stands for aqueous vermiculite dispersion.

Goodwin has been a leading global supplier of vermiculite since the 2007 purchase of Dupré Minerals’ manufacturing plant and customer list. In 2015 they announced their patent for AVD for use as a fire extinguishing agent, which runs until 2032.

Sales started to take off from FY21, as industry sectors, insurance companies and accreditation bodies woke up to the need for specific products and standards for lithium battery fires. Sales doubled in FY22 and again in FY23, from a very low base. To put this in context, total revenue for the Dupré Minerals subsidiary rose from £11.2m in FY20 to £15m in FY23. Dupré has reduced low-margin horticultural bulk vermiculite sales over the same period, meaning that AVD may have reached c.£4-6m of sales by FY23. See Dupré Minerals chart below.

In the first half of FY24, AVD sales matched the total for the previous full financial year. Underwriters Laboratory certification was achieved in 2023, which has opened up substantial opportunities in the US.

Goodwin is significantly expanding Dupré’s facilities to meet anticipated demand, which is certainly encouraging. The product range includes fire extinguishers, fire suppression kits and a battery fire blanket.

As a patent-protected product, the margin potential for AVD should be high. Goodwin is working with its key distributors in each country to seek regulatory mandates for high-risk businesses (such as garages repairing EVs) to have appropriate fire extinguishers on site.

I include a £4m incremental profit contribution for AVD in my base case forecast, which I see as corresponding to c.£20m of sales. £10m of blue sky potential would depend on regulatory success.

Hoben – second calciner and third ball mill signify growth ahead

Hoben International is Goodwin’s mineral processing subsidiary in the Peak District. It possesses plant including a calciner and state-of-the-art precision-controlled crushing, screening and ball mill capabilities. These are used to produce key raw materials for the jewellery casting powder businesses within the group. Hoben also processes various special sands, flours, high grade bauxite and siliceous mixes for a range of UK-based external customers. “Contract processing of more specialised raw materials” is also offered.

Last year’s group annual report highlighted a double expansion at Hoben, with the addition of a second calciner (for investment casting powder growth) as well as a third ball mill, which is needed “to increase capacity to accommodate continued growth in ground silica sales”. The Hoben accounts at Companies House further highlighted “Growing demand for silica flour in the UK for new applications has resulted in a healthy increase in sales within the year”. The specifics of the new application are mysterious, but it must be significant to justify the new investment.

Another niche growth product within Hoben is SoluForm. This is a patented range of biodegradable bags for the placement of concrete around rivers, to ensure that cement fines are not able to leak.

Hoben is small but its growth profile is impressive, as my chart below shows. I include a £2m uplift in my base case for further growth.

Financial review

Goodwin has sustained a high rate of reinvestment in percentage terms, as my chart below shows.

In absolute terms, the cumulative capex investment has been £182m over the last twenty years. This has been money very well invested in view of the £25m in EBIT it supports, let alone if Goodwin reaches £51m of operating profit in the near term as per my estimate.

It is worth labouring the point that Goodwin’s world-class facilities could have cost twice as much to build in less careful hands. The parsimonious approach at Goodwin has been to look for used equipment, including from liquidation sales of less fortunate foundry and machining competitors in the UK or overseas.

Goodwin operates a sensible balance sheet with a moderate amount of debt. My chart below shows net debt was £34m at April 2023, equivalent to 1.2x net debt to EBITDA. At the half year point in October 2023, debt had jumped to £56m, or 1.8x leverage, driven by many of the incremental capex projects and expansions I detailed above. Interest expense is low for Goodwin thanks to the well-timed interest rate swap they took out in July 2021, fixing £30m of notional debt at less than 1% for ten years.

Goodwin is careful about working capital management, and over the years the directors have been ever-conscious of the possible risks of over-trading at times of rapid expansion. I expect the next two years to be such a period. However, I expect debt to remain well under control thanks to the strong profitability and a reduction in capex.

Goodwin’s share count has been essentially unchanged over time. The introduction of an equity LTIP from 2016 led to 7% cumulative dilution by April 2023. This was partially reversed in June 2023 by the 2.3% tender offer and buyback that I described above.

Estimates and valuation

Plugging my base case scenario for £51m of OP in FY26E into the overall P&L delivers the following estimates.

As can be seen, the stock trades at 14.7x P/E in April 2026 on my £51m OP base case. This is attractive for the strong growth profile, if not outrageously cheap for a small and illiquid stock that serves a number of cyclical end-markets. The stock would produce a strong >20% IRR if this scenario plays out, in my view.

I also show the 8.0x P/E multiple that would apply to my ‘blue sky’ scenario of £91m OP. The stock would likely be a multi-bagger from today’s price, in the event that the blue sky scenario is achievable.

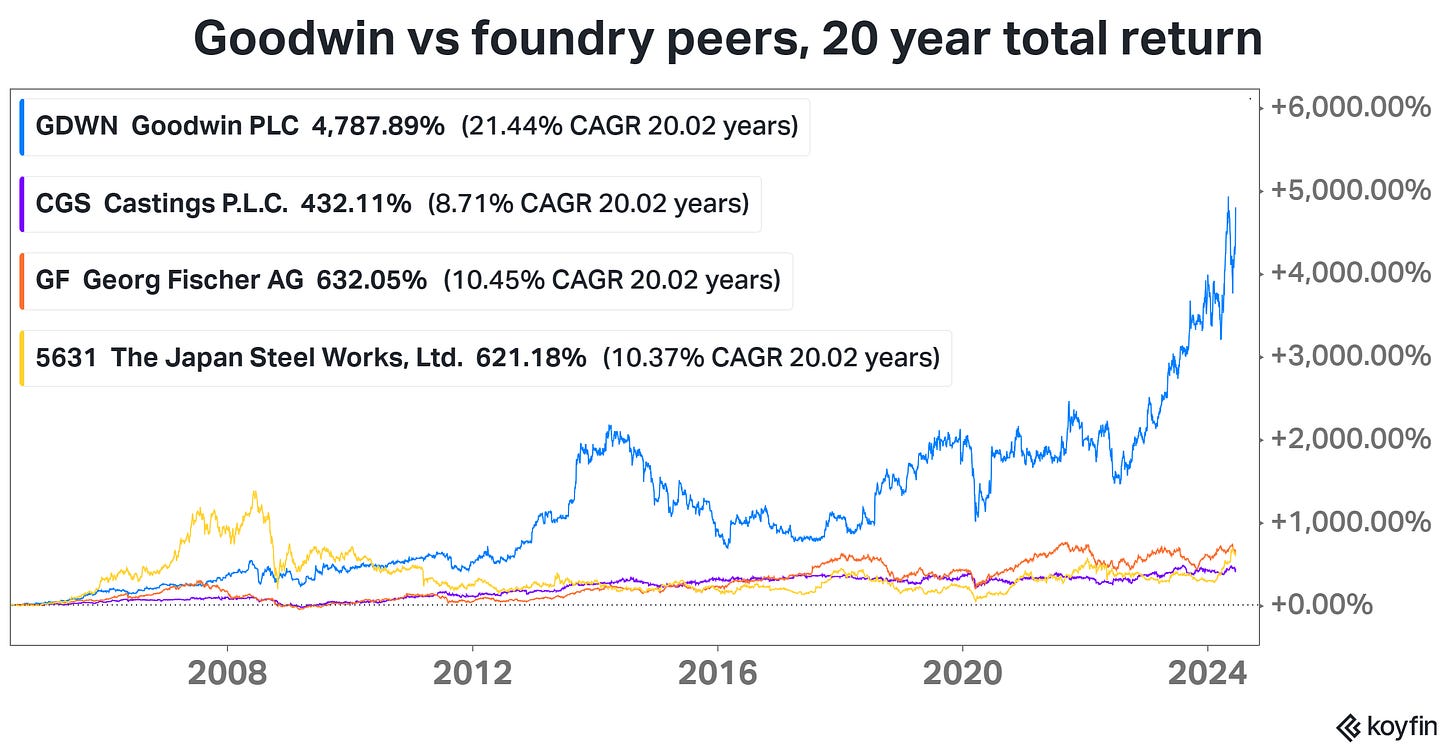

Over the very long term, Goodwin has outperformed other foundry and metal processing stocks, thanks to its ability to pivot and to grow its business with profitable diversifications. My chart shows Goodwin’s outstanding 20 year return compared to three other best-in-class foundry operations, namely Castings of Walsall, Georg Fischer of Switzerland and Japan Steel Works.

However, I note that on 5 and 10 year time periods, Goodwin’s return is rather more ordinary, since the 2014 and 2019 starting points happen to be the two prior peak years for profitability.

Annex – management and the long term approach

Goodwin’s directors and executive management are dominated by men named Goodwin.

The current board includes the two managing directors Matthew Goodwin (43) and Simon Goodwin (40). They run the Mechanical and Refractory divisions respectively. Also on the board are executive chairman Timothy Goodwin (34) and executive director Bernard Goodwin (37).

Still heavily involved are the prior generation, John W Goodwin (72) and Richard Goodwin (69). They served for 27 years as chairman and managing director respectively, from 1992 to 2019. They continue to serve on the Audit Committee.

The unusual board and committee composition, as well as several other practices, mean that Goodwin is in non-compliance with 16 of the provisions of the UK Corporate Governance Code. Under the “comply or explain” principle, the company puts forward a good argument that as a smaller company, its arrangements are the optimum compromise that is beneficial to shareholders’ long-term interests. I would tend to agree.

It is worth highlighting a couple of specific examples of the long-term approach in action at Goodwin.

Skills. The company has an ongoing requirement for talented and technically skilled workers. Given the skills shortage in the local area, Goodwin has been training its own apprentices for the last 13 years in its own Training Centre. To date, 300 apprentices have completed the course, the vast majority of whom are still working within the various subsidiaries.

The chart below shows that groupwide headcount was held flat from FY15 to FY23, reflecting strong efficiency improvements. I expect to see the headcount start to increase again from FY24, given the many growth projects across the group.

Climate change. Despite operating in energy-intensive sectors, Goodwin has long taken initiatives to reduce its environmental footprint, and also costs. They have installed extensive solar panels where possible, and recently received planning approval for a 4.3MW solar farm near Hoben International. Most ambitiously, they aim to achieve the first zero-emissions foundry by planting an offsetting broadleaved woodland in Wales.

Thanks for the write up. Lots to play for. Live the fact that although Shore Cap is nominally the broker, they put out one note a year. Totally under researched. I think was the only institutional holder when at AXA IM.

My name is Richard Goodwin - I'm not related but if 30+ years ago I'd just put my money in this one share (based solely on the name) instead of a sensible, balanced portfolio then I'd be a lot better off!