Viva Energy – retail transformation story at 10x P/E

(VEA.AX, USD3.4bn market cap, USD10m ADVT, 71% free float)

Australia’s petrol stations are mostly stuck in the dark ages. You can refuel your car and buy cigarettes, but don’t expect an inspiring choice of fresh food or quality coffee.

One provincial independent built out a world class offering – OTR in South Australia. Their 226 stores just became part of the listed Viva Energy. It plans to open new OTR stores, and to convert up to 80% of its own 800-strong estate to the OTR format. There is even a Guzman y Gomez kicker.

Viva is a transformation story in the making, from volatile energy ugly duckling to smooth convenience retail swan. This could deliver a triple whammy of higher sales, higher margins and a higher justified multiple for the stock, which currently trades on 10x P/E.

The key risks are around execution. Right now the numbers are messy, replete with transaction and transition expenses. A period of investment and rebranding is needed before proof of success can shine through. And Viva’s top team, though well proven as energy operators, are lacking in retail experience.

In my view, the starting valuation is cheap enough to make Viva an attractive asymmetric bet. Upside in case of success is as high as 100% within a couple of years. To the downside, even if the transformation disappoints, business as usual will deliver solid earnings and cash flow.

I’ve started a small position in Viva. I funded this by selling Sigma Healthcare, where I fear the ACCC may block the Chemist Warehouse deal, and CW may walk away to pursue an independent IPO.

In this post I cover the following.

· Background to Viva Energy and key management

· Refinery earnings profile – volatile but now with capped downside

· Commercial & Industrial – attractive and profitable

· Convenience strategy, driven by OTR

· Financial review

· Estimates and valuation

· Annex: fuel retail competitor profiles and recent transaction details

Background to Viva Energy

Viva Energy is the former Shell Australia downstream business. It is a relatively new entity on the Australian stock exchange, just marking its sixth anniversary since its July 2018 IPO.

However, Viva’s CEO has been in place a lot longer. He is Scott Wyatt, a New Zealander who farmed rabbits as a teenager. He joined Shell in around 1988 in New Zealand, and moved to Australia in 1992, and then to Singapore for a three year stint. From 2006, he moved permanently to Australia. Ever since then he has been effectively managing the same supply and distribution assets Viva owns today.

In 2014 Shell sold the Australian business to a Vitol-led consortium which renamed it Viva Energy. Wyatt had worked on the sell side of the deal for Shell. Vitol asked him to stay on and continue to manage the business.

In 2016 Wyatt oversaw a sale-and-leaseback of the properties, which were listed as Viva Energy REIT (now Waypoint REIT).

In 2018 came the full IPO of Viva Energy at A$2.50 per share. Vitol retained a 46% stake until September 2023, when it sold 16% in the market at a A$2.87 bookbuild price to end up at 29.9%.

Energy & Infrastructure (Geelong refinery)

Geelong Refinery, near Melbourne, came on stream in March 1954. It was further developed and added to in the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s and 2000s.

At peak, up until the year 2000 or so, Australia had eight or nine refineries in operation that met virtually all domestic fuel demand.

In the current century, Singapore and other Asian countries opened new, large and highly efficient refineries. These outcompeted the relatively small and old Australian refineries. Over the same period, Australian domestic crude oil production declined, meaning that remaining Australian refineries were in any case forced to import most of their crude oil feedstock. (Geelong uses only one-third local crude.)

Under these pressures, successive Australian refineries shuttered, leaving only two still standing today. Alongside Geelong is Lytton in Brisbane. Its owner, Ampol, has committed to keep Lytton in operation until at least 2027.

Geelong is a well-invested asset, with a capacity of 120,000 barrels per day and a relatively high Nelson Complexity Index of 9.44.

Both these metrics can be plotted on a chart as below, against a peer group of modern Asian refineries. Geelong is the red star – on the correct side of the line in terms of its viability in a global context. (The source is a Bain project based on 2015 data.)

On average, the refinery has delivered decent profits and cash generation. Unfortunately, in any given year earnings are close to unforecastable. The last two years have shown the full extent of volatility.

In 2022, the refinery contributed a record A$518m of EBITDA, as the Ukraine conflict caused regional refining margins to spike.

In 2023, earnings fell 87% to A$65m. As well as partial normalisation of margins, there was an accident when a crane dropped a compressor during a major maintenance turnaround. This delayed restart by several weeks. Despite an A$80m insurance recovery, the extended turnaround still had a A$193m yoy impact on profits.

My chart below shows the random number generator nature of refinery EBITDA.

The other refinery still open in Australia is Ampol’s Lytton refinery in Brisbane, which is slightly smaller than Geelong and with lower complexity. We can compare the EBITDA profiles of the two side-by-side: see chart.

I’m surprised to see that Lytton profit is always higher than Geelong, although that could be an artefact of different cost allocation between segments. Directionally they are always close to each other, with the exception of 2023 when Geelong’s crane incident hit hard.

During Covid, the refineries incurred big losses. The federal government was faced with the prospect of all Australian refineries shutting down permanently, a disaster for national energy security, unless it provided support.

In May 2021, then-PM Scott Morrison announced a generous fuel security package that put a floor under refinery earnings until at least June 2028. “You reduce your volatility of earnings, you get your cash support, you get your capex provided, it’s just a fantastic package,” as the veteran Bank of America analyst David Errington summarised on Viva’s conference call.

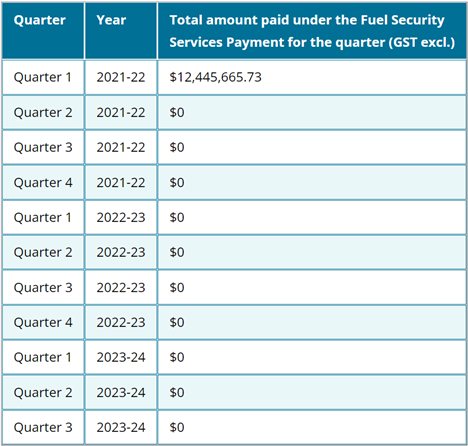

Since the FSSP was agreed, refining margins have generally been high enough to avoid triggering payments, as the table below shows. Nonetheless, it is reassuring for Viva shareholders to know that this downside protection is in place.

The refinery outlook for 2024 is uncertain as always. The benefit of a clean slate after 2023’s crane accident will likely be partly offset by weaker refining margins and higher shipping costs.

Regarding high shipping costs, Viva is at a relative advantage compared to its pure importer rivals. This is due to clean-dirty spreads! Clean product tankers (able to carry petrol) have far higher charter rates than dirty tankers (carrying crude or diesel), due to the high c$100k cost of cleaning a dirty vessel. This shipping market dynamic favours Viva. Its imports of crude for its refinery mean its total shipping cost skews dirty, compared to pure importer rivals who must stump up for lots of clean tankers to bring in their petrol.

Viva has various ambitious plans to future-proof the refinery by transitioning it to a hub for natural gas to Victoria, and eventually as a hydrogen facility. They are conscious of playing their role in the broader energy transition. However, any firm investment decisions will depend on government decisions and financial support.

In the meantime, battery electric vehicle adoption in Australia is low. Just 7% of new cars sold were BEVs in 2023, well below the US at 8%, UK at 17% and China at 25%. I expect liquid fossil fuels to be required for the next couple of decades, if not longer.

Commercial & Industrial

While the eye-catching opportunity is in retail, Viva has already built a great platform in its Commercial & Industrial business. Here Viva supplies diesel, jet fuel and speciality products to large customers in sectors such as defence, mining, transport, aviation, marine and agriculture. This is a bankable list of sectors in Australia’s economy.

Viva benefits from long-term relationships with its largest customers. E.g. the top ten customers in the segment accounted for 34% of EBITDA in 2022, with average tenure of twenty years.

Viva has been successful in winning long-term contracts. It attributes this in part to providing high-touch customer service from an extensive regional network (including 54 regional airports). Geelong Refinery supports the segment via its exclusive local production of military grade fuels, Avgas, polymers, bitumen and chemicals.

Most recently, in July 2023, Viva was awarded a six-to-twelve year contract to supply aviation, marine and ground fuel to the Australian Defence Force (ADF). This is another sign of government support for Viva given its strategic importance, which is comforting for shareholders.

The result of all of the above has been a steady recovery in volumes, since the hit from Covid in 2020, and strong progress in profits per litre. See my chart below.

This has driven segment EBITDA to double from the c.A$200m level seen before Covid to A$448m in 2023. Viva is quickly approaching the A$500m aspiration that it set at the November 2023 investor day. Analysts suspect that this is a target that can be comfortably beaten. See my chart below.

Convenience strategy

Ever since 2003, Viva Energy’s direct involvement in retail was severely restricted by an Alliance Agreement (predating Wyatt’s leadership of the business) that granted the supermarket giant Coles a long lease and licence to operate all of the shops across c.700 owned service stations, as well as set the price of petrol. The Alliance Agreement had an expiry date of February 2029.

At the time of IPO in 2018, therefore, Viva was pretty much just a fuel supply business with almost no direct retailing exposure.

Viva took back control in two stages. First, in February 2019, Viva renegotiated with Coles to take responsibility for retail fuel pricing and marketing. This allowed Viva to collect the full retail fuel margin for the first time, along with an enhanced royalty on convenience sales. Viva paid Coles A$137m for this favourable change, which came about after Coles made a mess of the fuel retailing challenge as the oil price rose, and saw fuel volumes heavily eroded due to uncompetitive pricing.

More recently, in September 2022, Viva agreed to acquire the entire Coles Express business for A$300m. In effect, they paid a premium to take back control of the convenience retail business six years earlier than scheduled, and with the benefit of friendly agreements on transitional support, continued Flybuys loyalty program membership, and continued supply of Coles products. The deal completed in May 2023.

OTR

The next key move, announced in April 2023, was to acquire OTR Group, a South Australia based operator that is regarded as best of breed for its sophisticated convenience and restaurant offer. This deal cost A$1.2bn and completed in March 2024, after severe scrutiny by the ACCC. To gain clearance, Viva agreed to transfer 25 of its own sites in South Australia to Chevron, in exchange receiving 13 Caltex / Puma branded sites from Chevron in other states.

The photos below illustrate the OTR offer.

· Barista-made coffee is in contrast to the machine offerings that are standard at most Australian convenience stores.

· Moe’s Dog & Shake is a simple but effective freshly made fast food offer, at a A$3.00 price point, that beats the plastic-wrapped meat pies found elsewhere. Moe’s advertising has been memorable and effective.

· OTR operates around 100 quick serve restaurants, including Subway and Hungry Jack’s (Australian Burger King) franchises.

· The Guzman y Gomez prospectus revealed OTR is a master franchisee for the whole of South Australia and surrounding parts of WA, NT and Victoria. It operates ten restaurants so far, with an extremely sweet deal signed in 2016. This includes a 43 year remaining term, a reduced marketing levy of just 0.75% of sales, and a reduced royalty rate of 4-5% of sales. The South Australian master franchisee is responsible for identifying and establishing its own restaurants, and has control over the quantity, timing and investment in new restaurant openings in its jurisdiction.

OTR integration plan

OTR can be seen as a reverse takeover of Viva’s retail business. The ambition is to have 80% of the existing network OTR branded by 2029. (The balance will stay as Reddy Express, the replacement brand for Coles Express.)

50% of those would be shop-only. 30% would be bigger projects to remodel, refurb or knockdown and rebuild with a full restaurant offer. See table below.

This will require substantial investments in former Coles Express stores in order to bring them up to OTR standard. Capex is guided as A$50m per annum from Viva’s side, plus the potential for significant landlord funding from Waypoint REIT, in exchange for new leases.

The potential return on this investment is high. The table below compares OTR’s shop metrics to Coles Express. Any progress in bridging the shop gross margin per store from A$0.5m to A$1.5m, when multiplied over 800 stores, could be a game-changer for Viva profits.

Even the transition to OTR’s app should be accretive, since consumers have reported that it works far better than what other retailers offer for coffee and food orders and fuel purchases at pump.

OTR was founded and built by a family business called Peregrine. The CEO, Yasser Shahin, has been retained by Viva Energy as a consultant for two years, to support the transition of the business to Viva’s own head of retail, Jevan Bouzo.

Yasser Shahin and his brothers retain extensive business interests in Peregrine, including real estate. (They will own the OTR freehold portfolio and be landlords to Viva.)

Shahin is also an endurance motor sports fanatic, who races around the world with a Porsche team. (He won his class at the Le Mans 24 hour race in 2024.)

A key risk for Viva is whether they will be able to learn the OTR “secret sauce”, and continue to grow the business successfully after Shahin ceases his involvement. The lack of proven retail experience among Viva’s leadership increases the execution risk. Mitigating this, there is an entire OTR leadership team beneath Shahin that will continue to run OTR, and also Viva’s combined convenience business, from its Kensington, Adelaide head office. The strength of the OTR business and offer should prevail.

Jevan Bouzo joined Viva in 2015. As CFO he led the company through flotation. In 2021 he was promoted to an expanded role of Chief Operating and Financial Officer, taking on supply chain operations. Then from the start of 2023, he was promoted again to Chief Executive, Convenience & Mobility.

In this role, he has direct responsibility for integrating and transforming the Coles, OTR and Liberty stores. Crucial decisions include the scope and pace of investments in individual sites, execution on an expanded and more attractive retail and food offer, and setting the right balance in pricing between margins and value to customers.

Convenience earnings outlook

Historic earnings in the Convenience & Mobility segment have been flat from 2017 to 2023, as shown in my chart below.

At the start of this period, Viva was effectively just a fuel wholesaler to the petrol stations operated by Coles and others. From 2019, Viva took control of fuel retail from Coles, but any benefit was derailed by Covid which hit volumes hard. Then from May 2023, Viva had the full Coles Express retail convenience business… but it added zero incremental profit in the first eight months of ownership, as high overheads and transition costs offset the incremental gross margin.

Below is the bridge to >A$500m EBITDA that Viva shared at its November 2023 investor day.

The Coles Express acquisition benefits are conditioned on a fuel volume uplift to 65-70 million litres per week. This is not currently on track: volumes seem to have stalled at 58mlpw, as per my chart below. Investors will be watching closely at the H1’24 results to see if Coles Express makes a positive contribution in the first half. However, management have flagged that the end of the TSA in May 2025 will be a key event for lower overhead and improved profit contribution.

The rest of the earnings bridge is mainly from the OTR business itself, and its synergies, new store growth and conversion of existing stores, as discussed above.

Liberty Convenience is another piece of the puzzle. This is a 110 site regional network that Viva has long held as a JV with “the Davids” (David Goldberger and David Wieland). In 2019 Viva took full control of the wholesale business, but left the retail operations in a 50:50 JV operated by the Davids. This arrangement came with a put and call option for Viva to buy in the whole of Liberty at the end of 2024. They intend to exercise this and add another 110 controlled stores to their nascent convenience retail business, subject to ACCC approval.

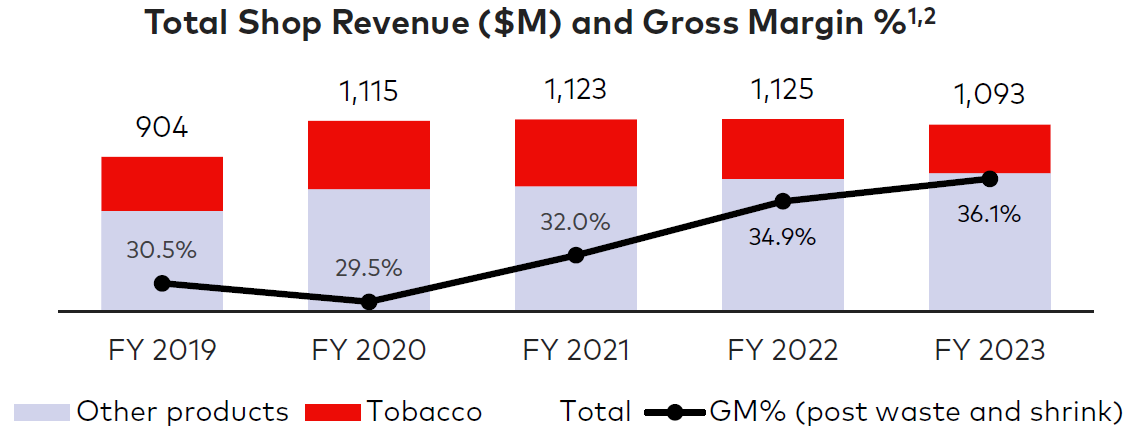

Tobacco should be mentioned as a fast-changing area, which impacts top-line and gross margin mix more than bottom line. Both Viva and its rivals saw drastic double-digit falls in tobacco sales in 2023, blamed on increased vaping and illicit tobacco. The falls look set to continue. OTR also includes a tobacco wholesale and retail operation which is subject to the same pressures.

Viva does not publish the exact mix of tobacco sales, but for Ampol this used to be as high as 40%: see chart below.

Financial review

Viva Energy’s historic numbers are difficult to interpret for several reasons.

RC vs HC: IFRS accounting requires a Historical Cost presentation, resulting in large gains and losses resulting from timing differences between purchases and sales of inventory, and the rise and fall of oil and product prices during that time. Viva presents an additional non-IFRS metric of Replacement Cost to remove the timing effects.

Lease accounting also changed a couple of years after Viva’s IPO. It continues to use the superseded AASB 117 standard for RC earnings, as well as using the AASB 16 current standard for the statutory accounts as is required.

One-off items of various kinds are adjusted out of RC earnings. These will be bigger during the current period, including transaction and transition costs.

Change of scope: even if we had clean and consistent historic results, they would be of limited guide for the retail segment, given the huge change resulting from Viva’s completed acquisitions of Coles Express and OTR, and its intended acquisition of Liberty Convenience.

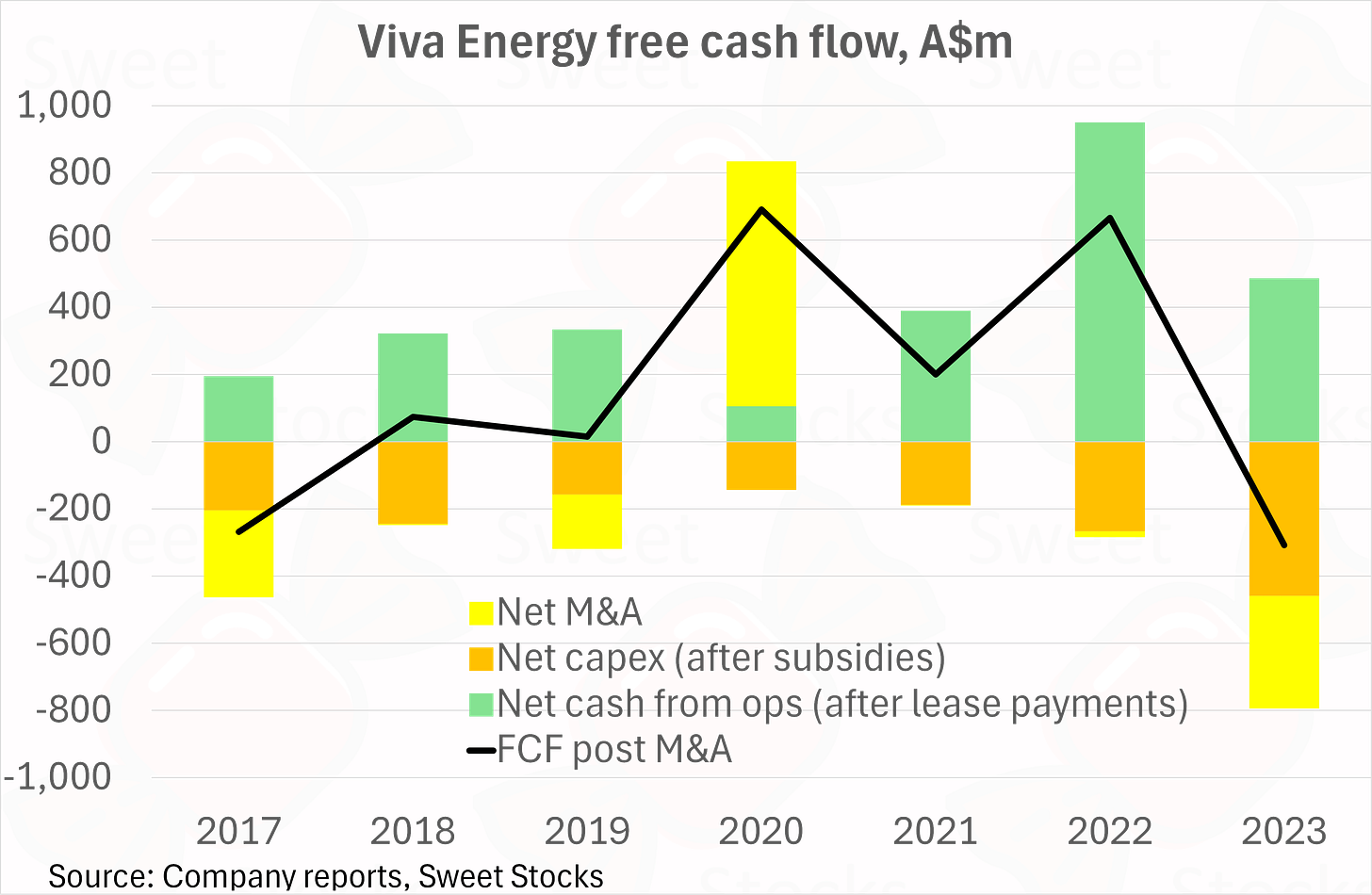

In circumstances where the profitability track record is hard to read, free cash flow is even more important. Below is my chart showing net cash from operations (green) less capex (orange) and M&A (yellow). The black line sums these three items to show a strict definition of free cash flow, after all organic and M&A investment.

Free cash flow from 2018 to 2023 was A$1.3bn on a cumulative basis, including the disposal benefit of the REIT stake sale in 2020. FCF after capex but before M&A was A$1.1bn. Either way, the cash generation is attractive. Looking ahead, I expect increased underlying cash generation which will fund increased investment in expansion and conversion.

In terms of uses of cash, Viva paid out A$1.6bn in capital returns, buybacks and dividends from IPO through to the end of 2023. Net debt excluding leases remained very low throughout that time – see chart below. In March 2024, the A$1bn cash component of OTR consideration was funded by debt. Viva targets net debt to underlying RC EBITDA of 1.0x to 1.5x. They will continue to pay out around 60% of net profits, while funding the transformation with the balance of cash flow.

Including capitalised leases, net debt was A$2.8bn at end of 2023, and will be much higher with the OTR impact. I am not concerned by the high lease debt, given the steady nature of the corresponding fuel and convenience revenues.

Estimates and valuation

My estimates are shown in the table below. I am above consensus for 2024E to 2026E (based on ten contributing analysts). I am in line for 2027E, based on just two contributing analysts.

On my estimates, the stock is cheap at 10x current P/E, falling to 7.5x in 2027E. Refinery becomes a far smaller part of total profits, which should justify some re-rating.

Since IPO, the stock has traded at anywhere from 8x to 20x P/E, affected by whether refinery earnings were especially high or low at the time.

Viva has delivered an adequate total return since IPO, and has notably outperformed its closest peer Ampol. My chart below compares Viva to Ampol and also the best-in-class Couche-Tard and Casey’s. I wrote up Casey’s in February – see here. It is a far cleaner story that now trades at a high 26.4x multiple of next twelve month earnings.

Annex: fuel and convenience retail competitors

Ampol is the biggest player, and the closest peer to Viva. It was formed by merger in 1995 as Caltex Australia, owned 50% by Texaco (who became Chevron) and 50% by Australian shareholders with a listing on the ASX. Chevron sold its stake in 2015, and withdrew the licence to use the Caltex brand name at the end of 2019. Caltex Australia then rebranded itself and all its locations as Ampol, a historical name from the 1950s.

From September 2019, Alimentation Couche-Tard tried to buy Caltex (as it then still was). The original bid of A$8bn or A$32 per share was painstakingly negotiated up to A$35.25 by the Caltex board over the next few months. Covid intervened, and allowed Couche-Tard to walk away before it had signed a contract.

Ampol’s strategy also aims to improve its retail network and grow shop earnings. However, without the benefit of OTR it is starting from a far worse position. E.g. it just commenced a QSR trial with the first two Hungry Jack’s restaurants opened by the end of 2023 — lagging far behind the near-100 restaurants in OTR and the associated know-how to rapidly open more.

7-Eleven is the next biggest fuel and convenience retailer. It was privately owned by the Withers and Barlow families until April 2024, when the Japanese Seven & i Holdings completed a A$1.7bn acquisition. Ampol, Platinum Equity and a Malaysian listed trade player were said to be other participants in the auction.

7-Eleven has 751 stores, of which a third are company operated and two thirds are franchised. Network merchandise sales reached A$1.8bn in FY23, with a 38% gross margin. Total gross profit including fuel contribution was A$1.2bn, adjusted EBITDA was A$200m and adjusted OP was A$110m. Seven & i paid 8.5x trailing EBITDA before synergies.

7-Eleven’s store footprint is concentrated in city centres, and the new owner intends to accelerate new store openings. They also want to use their playbook from the US and Japan of building out a food supply chain and developing new fresh food and hot food offerings.

Chevron sold out of its Caltex JV in 2015, as mentioned above. They surprised everyone in December 2019 by re-entering the Australian retail market with the purchase of Puma from Trafigura. This was one of the largest independent fuel retail chains, with 360 fuel sites, 222 shops and dozens of cafes and truck stops. Chevron paid A$425m for a business with around A$50m of EBITDA.

EG Australia is part of the indebted EG Group empire, previously controlled by UK brothers Zuber and Mohsin Issa who are now splitting up. In 2018, EG bought a 540 store petrol retail business from supermarket giant Woolworths for A$1.73bn. In early 2020, they tried to muscle in on the Caltex auction with a rival bid to Couche-Tard’s. This went nowhere due to Covid.

More recently, things have gone wrong for EG, both in Australia and globally. Bloomberg’s lurid headline from April 2024 is self-explanatory: Britain’s Gas Station Billionaires Face Nightmare Down Under. They reported that EG is eager to sell the Australian business, after successive goodwill write-downs and a 15% drop in EBITDA in 2023.

Mike McMenamin has been CEO of EG Australia since Woolworths sold the business. As a former Caltex executive, he is highly experienced. The fact that EG overpaid and got caught with too much expensive debt does not necessarily reflect on his ability as an operator.

BP Australia has around 1,200 branded retail fuel sites around the country, of which 350 are company-owned and the rest are owned and operated by independent partners. In May 2024 BP acquired X Convenience, a small South Australia fuel and convenience retailer with 50 sites. Back in 2016-17, BP had agreed to buy the Woolworths estate, but the ACCC blocked the deal, and EG later bought it instead.

United Petroleum Group is a mid-sized player that supplies 450 retail sites, plus its own fuel import terminals. Most sites are operated by commission agents, with 60 sites managed by dealers.

Great write-up- The refinery is of course some kind of "poison pill". But still an interesting story.

Nice write up. Not sure if they can successfully transition the stores. Will be watching closely to see some more signs.